Meet Hugh Mendes, the contemporary artist taking famous obituary examples of great artists as his haunting modern muses…

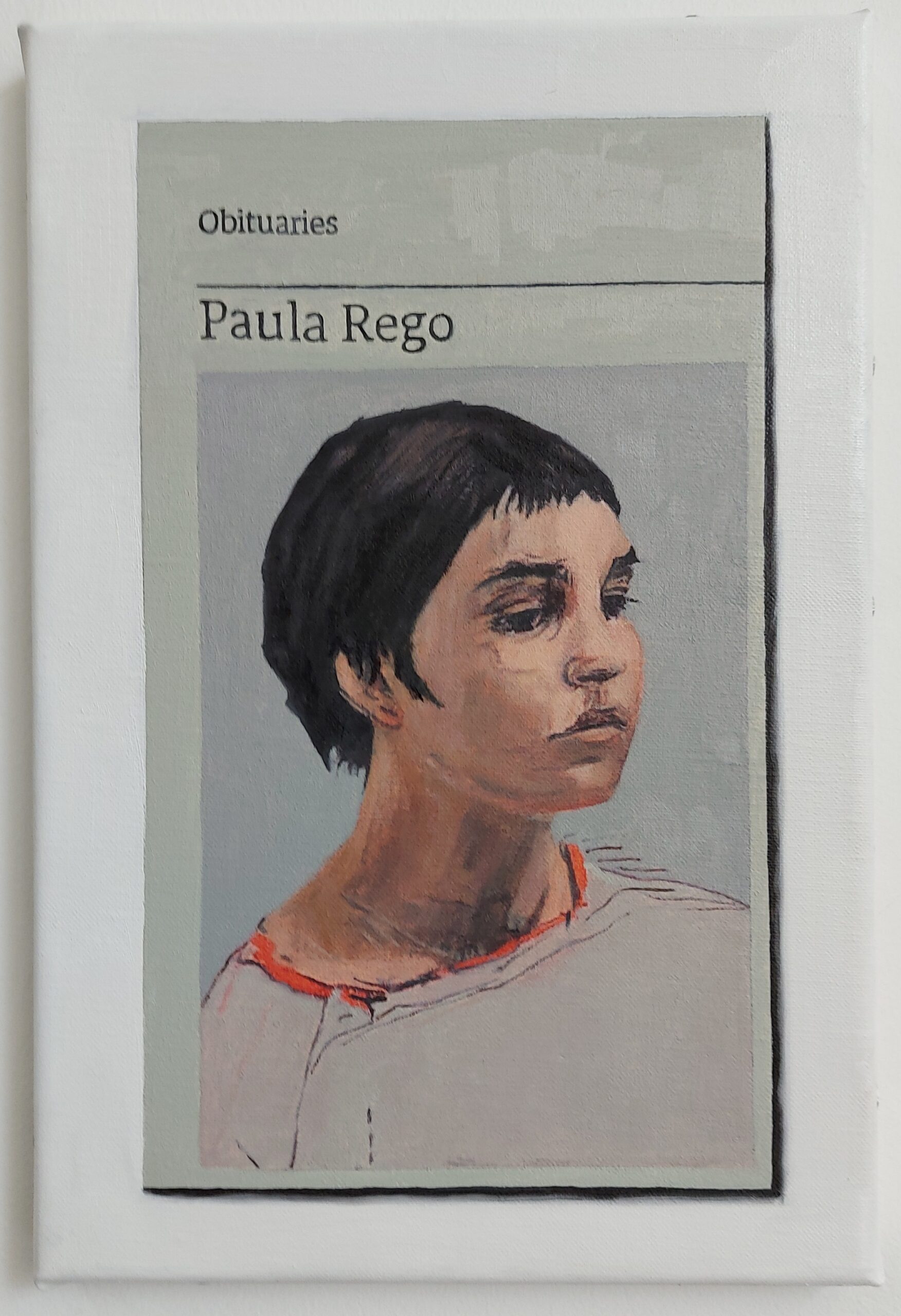

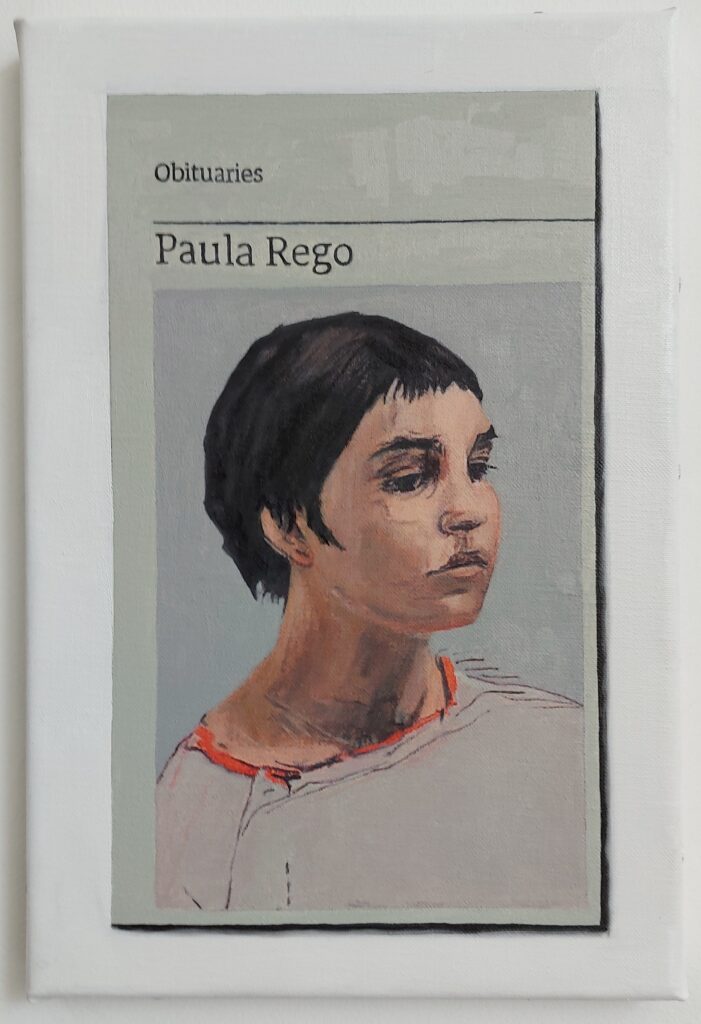

Where does an artist’s creative inspiration come from? What, or who, really provides this for them? It’s a question which has intrigued contemporary British painter Hugh Mendes for more than 15 years, reflected in his subject matter – notable, and many of them recognisable, figures from art history. While many narratives present us with a reductive vision of the passive female muse, whom the great artist relies upon as a submissive model, Mendes complicates this romanticised binary. With his ongoing and haunting series ‘Obituaries’, he instead presents the artist as muse.

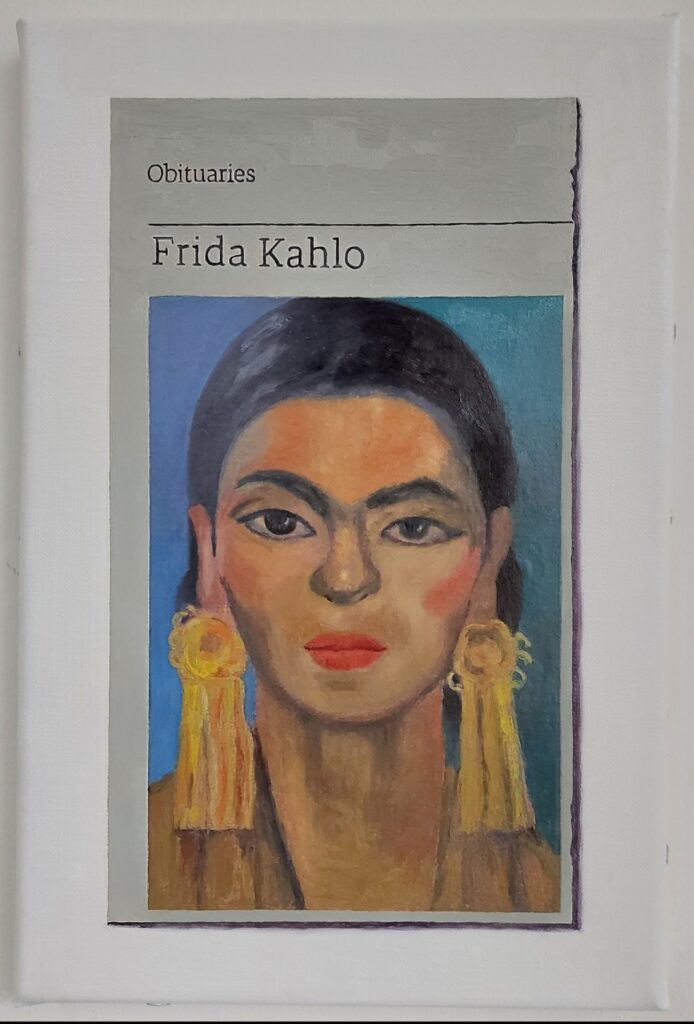

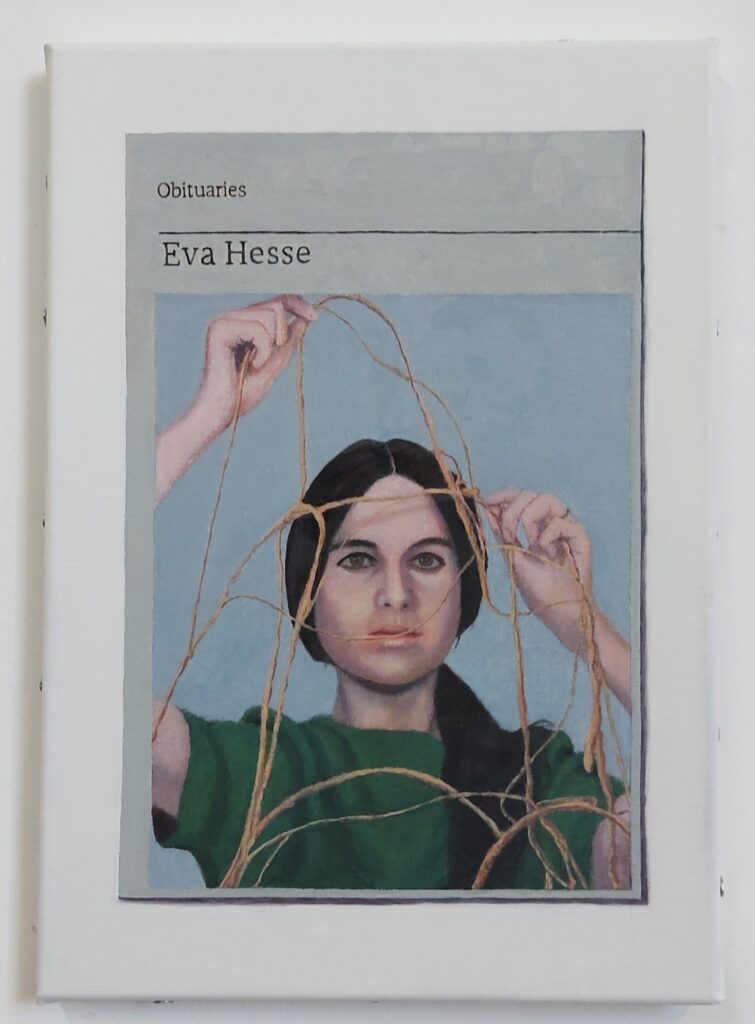

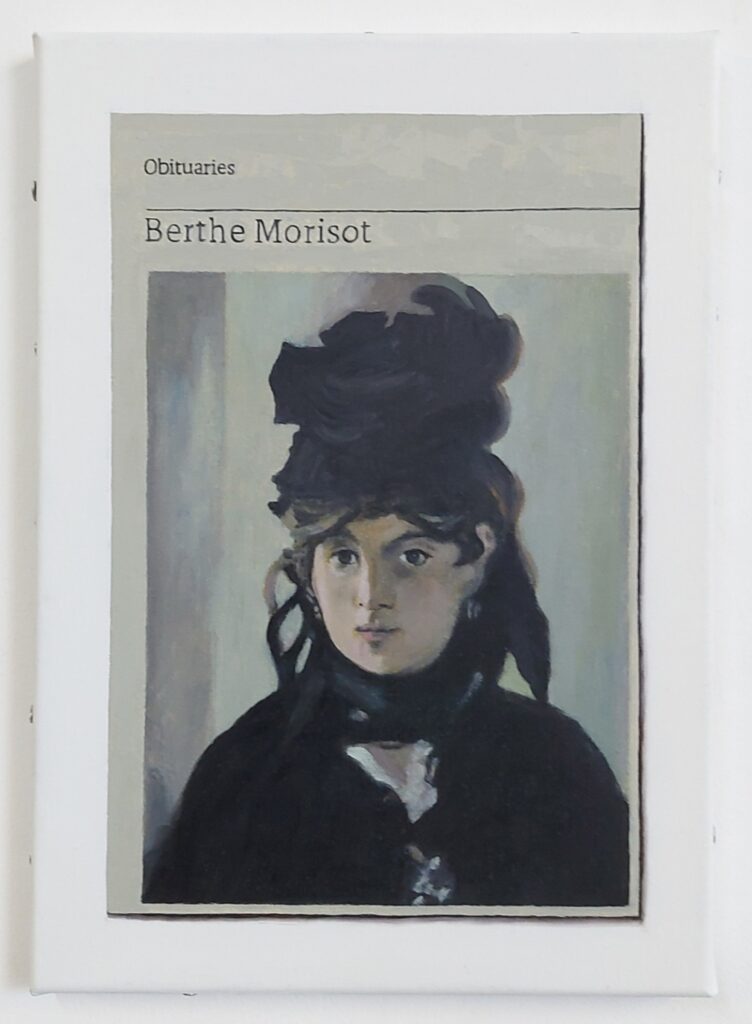

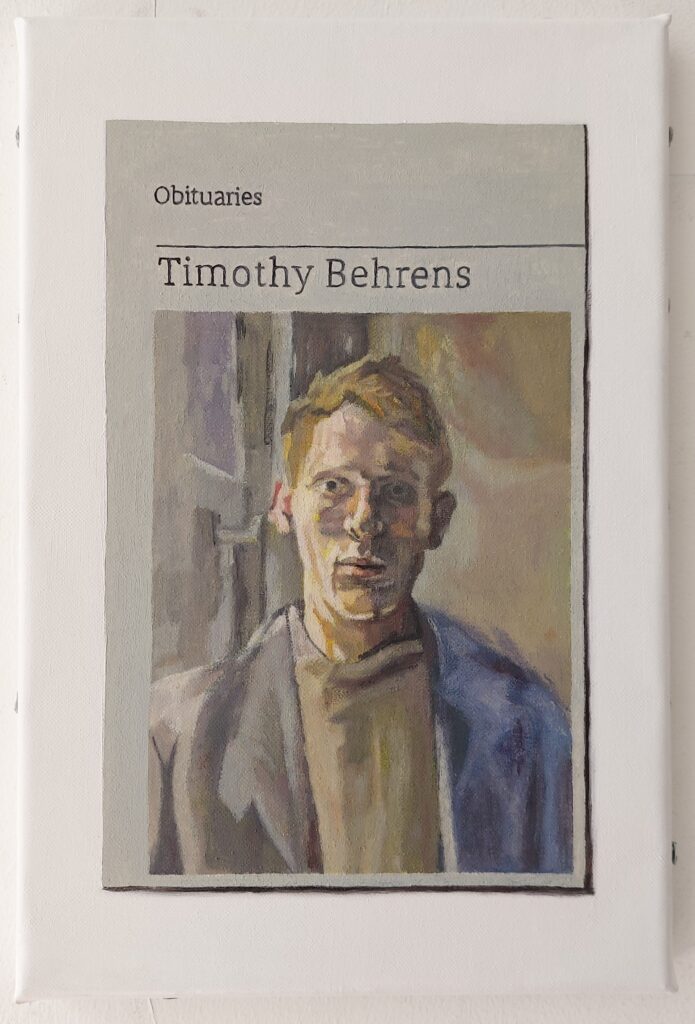

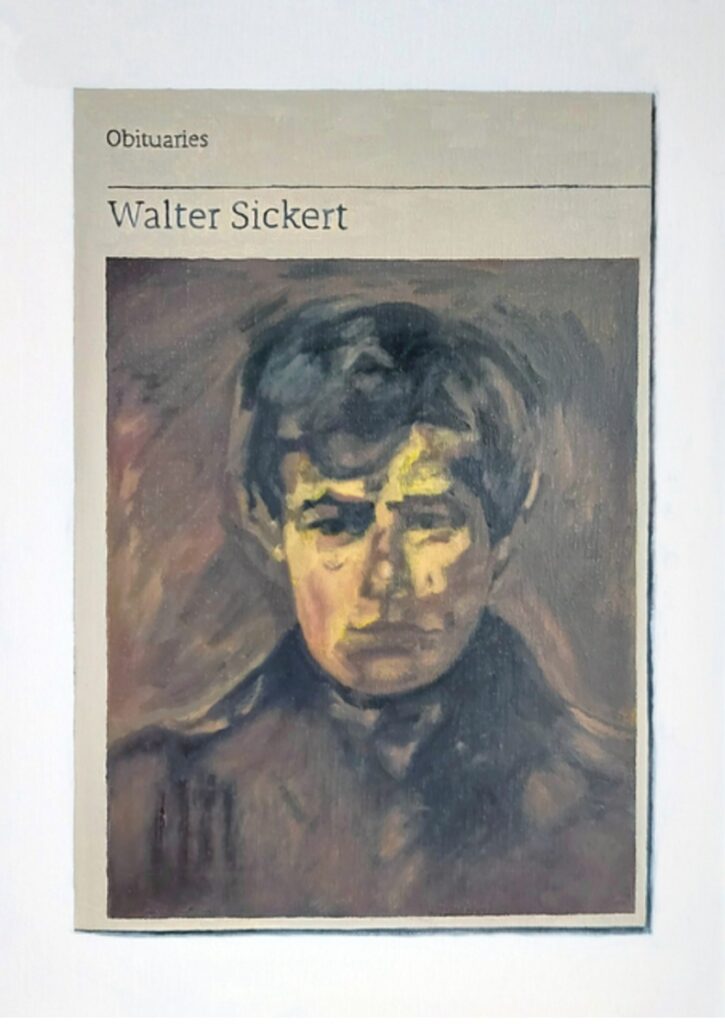

Sourcing self-portraits of dead artists, Mendes paints them in oils on linen, remaining faithful to the style of the original. He then frames them within a painted mock-up of the border of the obituary page of The Guardian or Independent. Subjects have included Frida Kahlo, Lucien Freud, Edgar Degas, Caravaggio, Jan van Eyck and Walter Sickert.

“It occurred to me that pretty much all the great artists of history have made self-portraits and so there was nothing to stop me going back through art history and making homages to all my heroes and mentors”, he explains.

“Every artist paints himself”, was the motto of the Renaissance. Mendes shows us how true this statement was, and still is, through his portraits of artists who have taken themselves as their own muses. With paintings based on self-portraits by the likes of Rembrandt, he invites us to read an artist’s work through their identity, and their identity through the work they have made:

“By using a self-portrait as image, I am engaging with their particular technique and style as well as how they saw themselves and how they wanted to present themselves to the world.”

Such images prove that the process of forming an identity is constructed, and both based on personal and other people’s perception of self. Mendes’ series certainly resonates with selfie culture and the notion of the constructed persona for the public to see, the selves we exhibit to the world and the many masks we all wear in a culture that demands images from us, in which we are both artist and muse.

Selfies are nothing new: throughout history, great male artists from Velázquez and Vermeer to Picasso have presented themselves, via self-portraits, as geniuses making ‘masterpieces’ alone in their studios. But this is, of course, a myth: no artist works in isolation, and they have often relied on studio assistants, muses, models, students and other artists for practical support and inspiration.

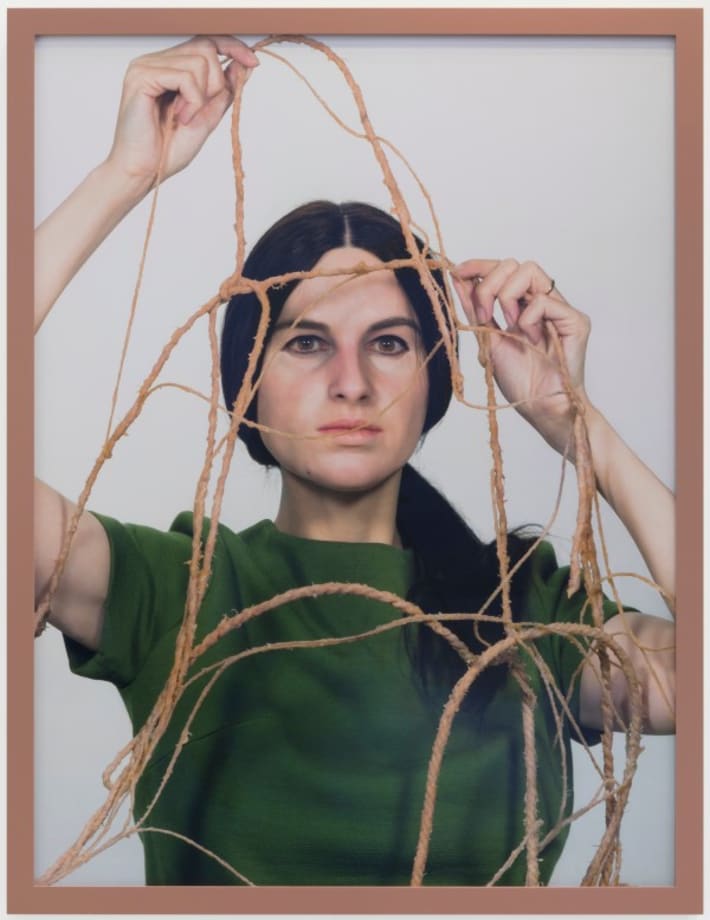

Mendes’ evocative series shows us that artists indeed take inspiration from one another. As Picasso – another of his subjects – once famously stated, “Good artists copy, great artists steal”. Recently, he has begun to work from portraits of famous artists created by other artists, including Gillian Wearing’s photograph of herself dressed up as American sculptor Eva Hesse, ‘Me as Eva Hesse’, 2019. By the time Wearing created this work, sculpture had become an increasingly important part of her own practice, in which she makes commemorative statues of everyday heroes, many of them women.

Gillian Wearing

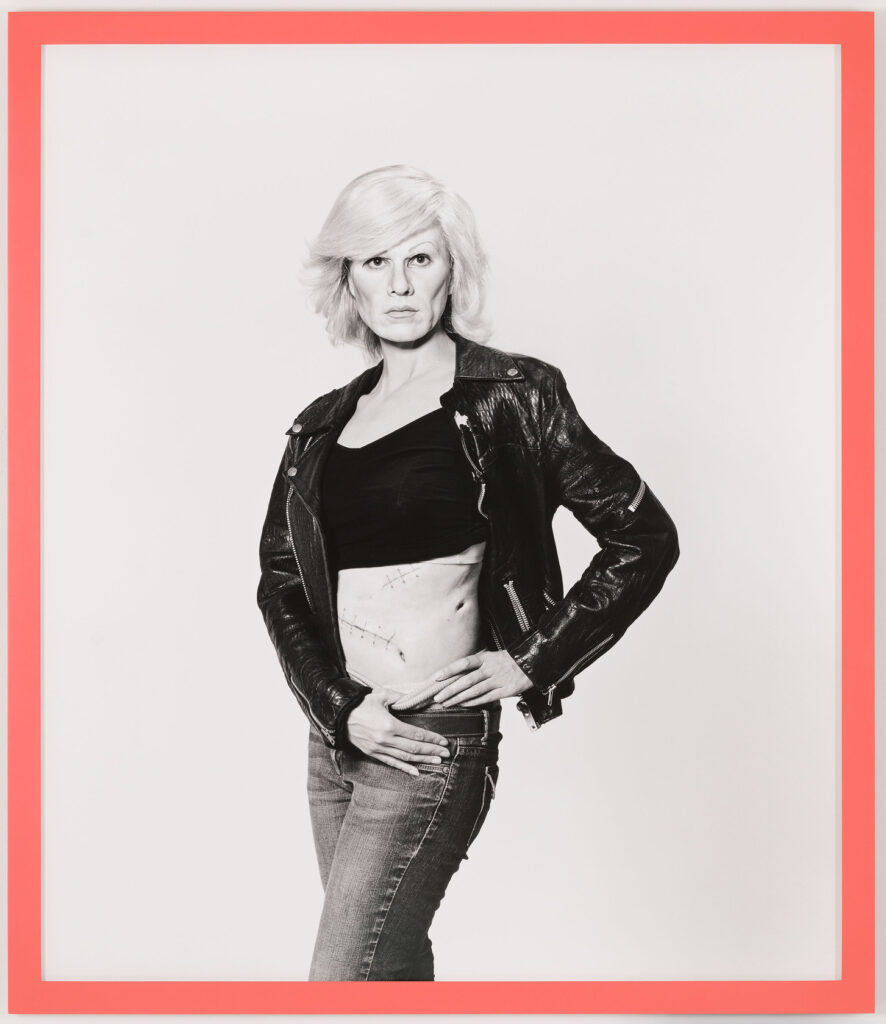

Gillian Wearing

Wearing has also dressed up as Andy Warhol, Marcel Duchamp and Claude Cahun, who famously explored themes around identity and gender, played out through masquerade and performance: “I am drawn to their work, I couldn’t have been an artist if there weren’t artists I admire, they are my spiritual family they give me the sustenance to make work. You can get so close to someone’s work that it feels almost like your own work, it helps you make sense of how you might bring something unique to the world as well”.

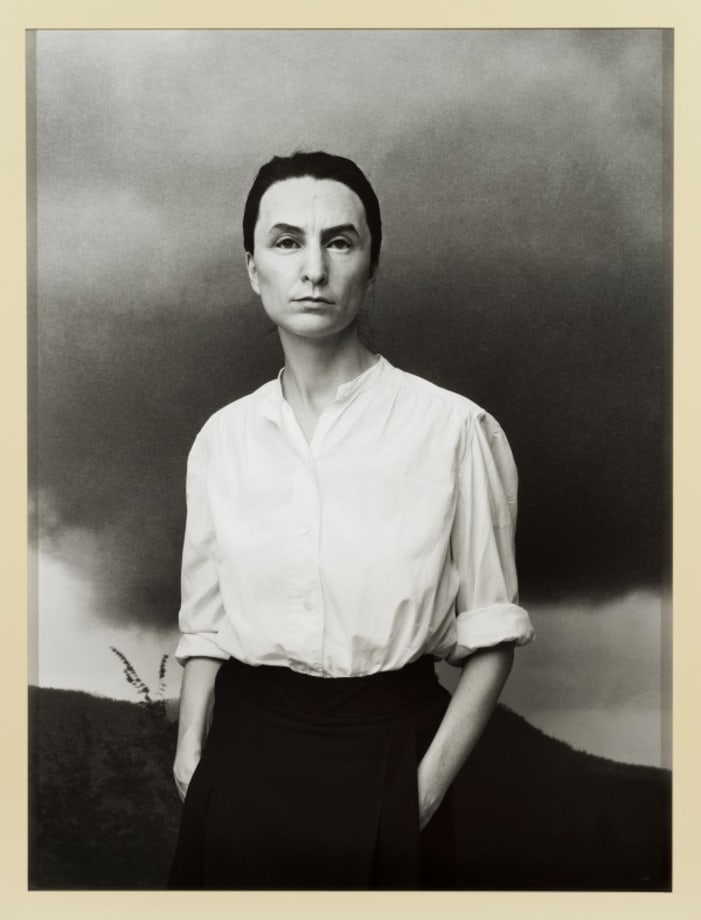

Another artist-muse from Mendes’ series is French Impressionist painter Berthe Morisot, based on a portrait by her contemporary Edouard Manet. Obituary portraits such as this importantly shine a light on the fact that many great women artists have been muses, and are known primarily for this role, rather than as artists in their own right.

Lucian Freud’s ex-wife and muse, Celia Paul, has frequently spoken out in interviews about how she ‘hates’ being referred to as a muse. Being framed in this light, she explains, casts a shadow over her own painting practice and identity as an artist. Dora Maar, Françoise Gilot, Emilie Flöge, Elizabeth Siddall and Camille Claudel are among a long list of others whose own practice have been cast in the shadows of their male artist partners, thus harming their careers and legacy.

But the term muse wasn’t always a negative one. At their origin in ancient Greece mythology, there were nine female muses who were gifted goddesses of the arts: music, dance, song, poetry and memory. Ancient Greek vase painting depicts them as animated young women, playing musical instruments, singing and reading from scrolls. Invoked by mortals, the muses inspired musicians, artists and writers, all of whom depended on them for divine creativity, wisdom and insight.

Similarly, today we should see the muse as a crucial part of the collaborative relationship, which is exactly how Mendes presents them. So many muses have been artists, bringing creativity to the relationship: Emilie Flöge’s fashion designs informed Klimt’s trademark style, Dora Maar’s political convictions influenced Picasso’s anti-war mural ‘Guernica’, and Siddall created paintings side-by-side with Rossetti. Such female artist-muses were appreciated for far more than their appearance; they created powerful dialogue with their male counterparts. Staring out of their frames, Mendes’ sitters demand to be seen, as they look on, seemingly challenging the viewer: how will you see me?

Indeed, Mendes’ ‘Obituaries’ invite us to seek out and read the stories of artists muses who he has selected, including those great women artists whom history has overlooked and forgotten. He helps us see that muse need not be negative term, but instead we should see these figures as crucial to art history. Mendes also illuminates the fact that many individuals have been, and continue to be, muses for more than one person – Hesse has been both a muse for Wearing as well as for himself: “Kind of double muse!”. Inspiration can ripple on, with no end to its flow.

Moreover, male artists can be muses, too, including Francis Bacon whose portrait was painted by Lucien Freud and Emile Bernard, who sat for Toulouse Lautrec: both have been taken as subjects by Hugh Mendes, broadening out the definition of the muse beyond gendered terms. Challenging traditional notions of the relationship between artist and muse, Mendes masterfully celebrates his various sources of inspiration and presents great artists of the past as his many influential muses, who merit recognition.

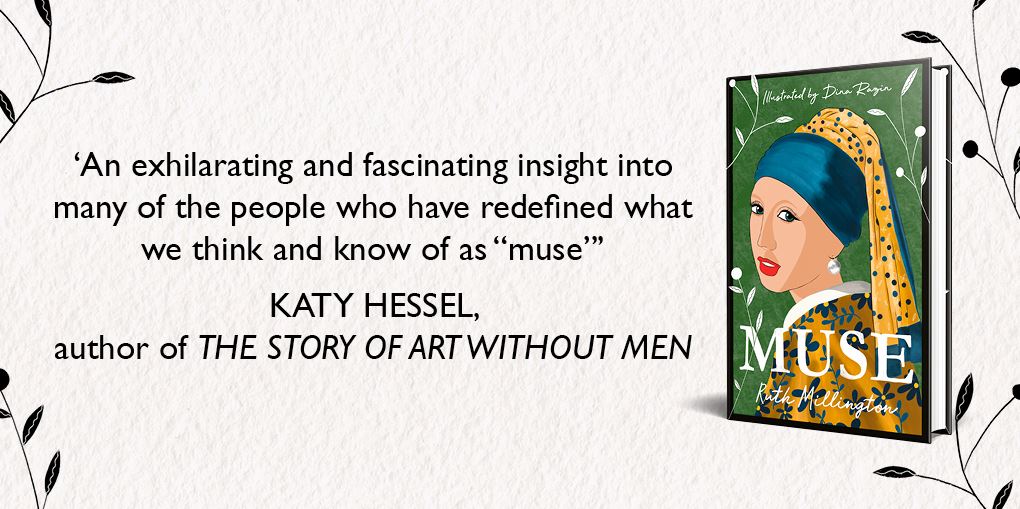

Charlie Smith London will be showing a selection of Hugh Mendes’ Obituaries at the 2023 edition of London Art Fair, through an exhibition titled ‘Reframing the Muse’, which I have curated, based on my book MUSE.