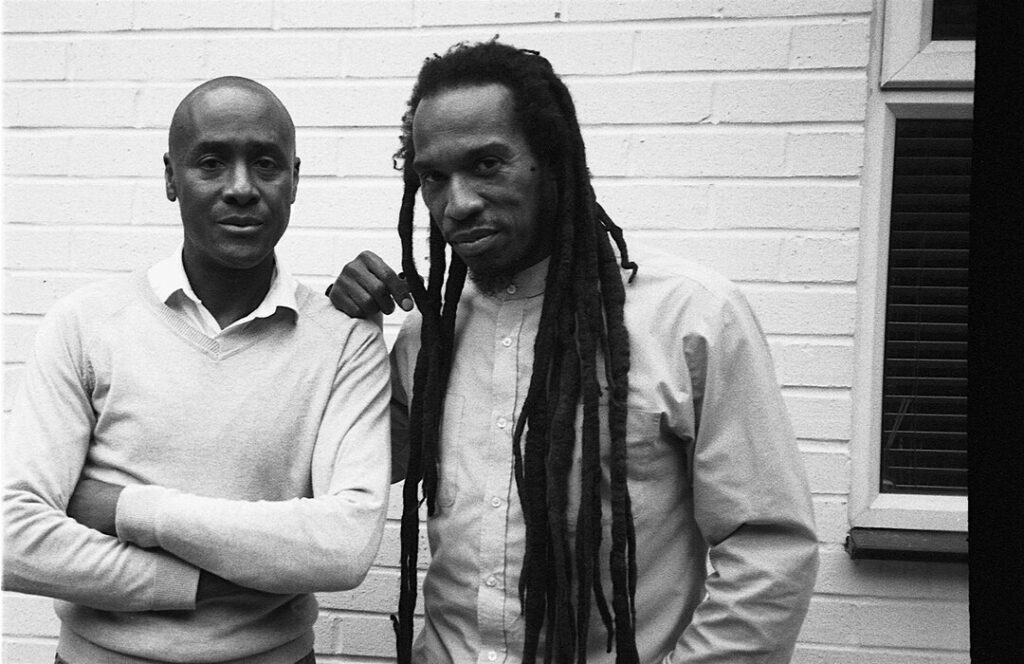

38 years ago, Handsworth was inflamed with anger: cars were upturned, shops were burnt and looted, 35 people were either injured or hospitalised, and two people lost their lives. In the aftermath of the Handsworth Riots well over 1500 police were drafted into the area. A traumatic event in Birmingham’s history, even today people still ask, “how could a tiny spark turn into such a gigantic flame?”, says Pogus Caesar. Collaborating with Benjamin Zephaniah, he has produced a provocative new film that addresses that very question.

Returning home after a day’s work at the West Midlands Ethnic Minority Arts Service, Caesar received a frantic phone call from a friend. He switched on the radio to hear a BBC West Midlands reporter announce, “There’s a riot in Handsworth”. It’s a refrain that echoes through the emotive film, which combines poetry, photographic stills, interviews, video and a specially composed soundscape by underground artist TaberCayon, which energises the story.

This is Caesar’s side the story, at least. “Everyone you ask about the Handsworth Riots will have something different to say”, he points out. “There are so many stories”. ‘The Tiny Spark’ is what Caesar refers to as his “reinterpretation of the events from a conceptual viewpoint”. The film opens with Caesar’s words on screen, giving context to the images which follow:

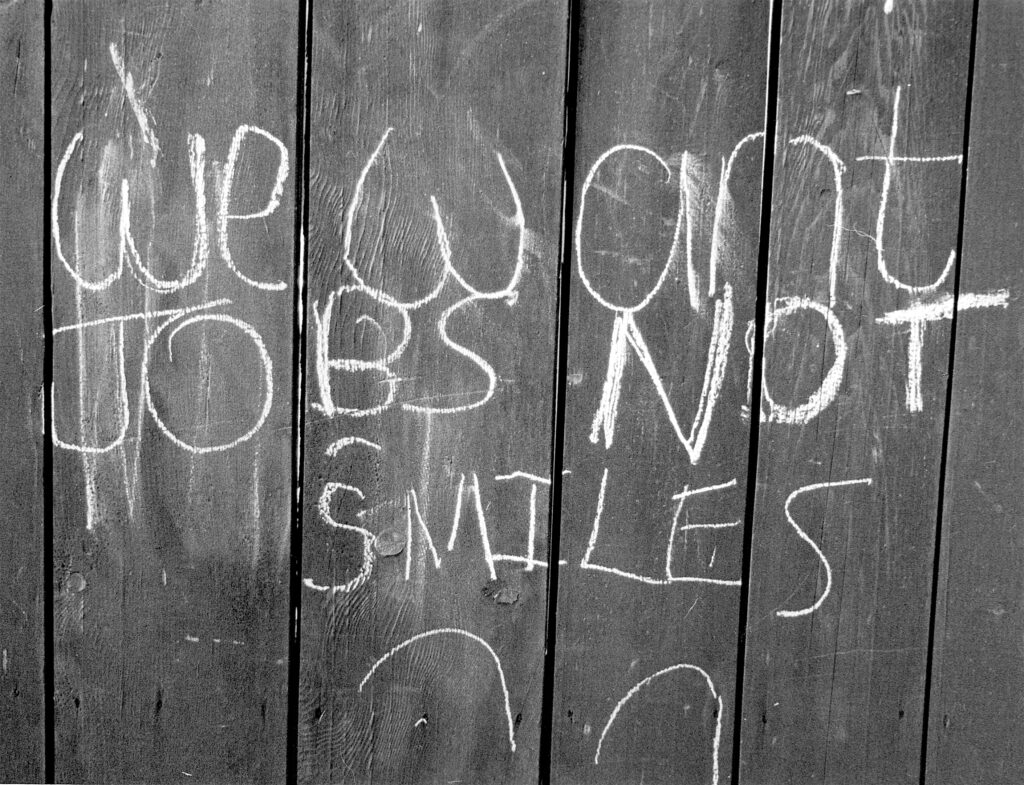

“At approximately 5pm on Monday 9th September 1985 an African Caribbean man was arrested near the Acapulco Cafe, Lozells Road for a traffic offence. Very soon a crowd consisting of African Carribean, Asian, and British people ask the police to let the man go; the police refused the request and the situation escalated into a riot. By 7:30pm, the Villa Cross Bingo Hall and Social Club was on fire; firemen tried to control the flames but the crowd said, “let it burn”.

Having never photographed anything like this before, Caesar arrived on the scene with the 35mm Canon camera that he still uses today. Although afraid that he “might be hit by something, or arrested by the police”, he spent hours “running on adrenaline”, weaving through back alleys amid smoke to photograph the action from different, close-up vantage points.

For safety, Caesar would repeatedly pocket his camera, before pulling it back out to frame the next shot, with one intention: “to document the riots from my own perspective”, he says.

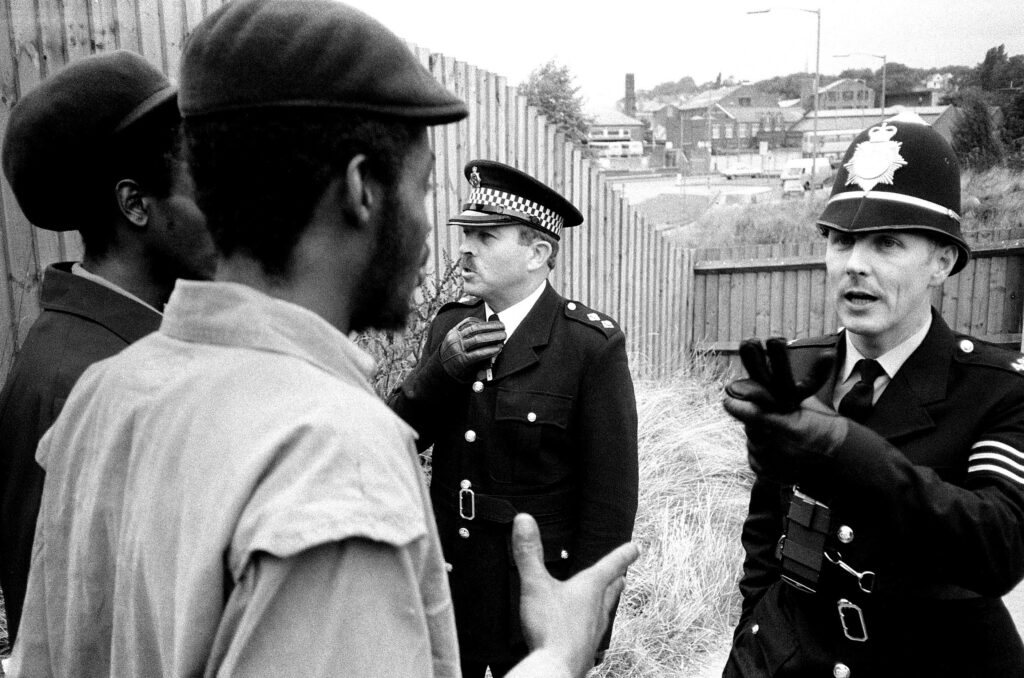

There’s an immediacy to his black and white photographs which show police advancing with helmets and shields, burnt out cars on the road, a fearful woman peering through net curtains, and spiralling smoke from petrol bombs, taking on a surreal quality.

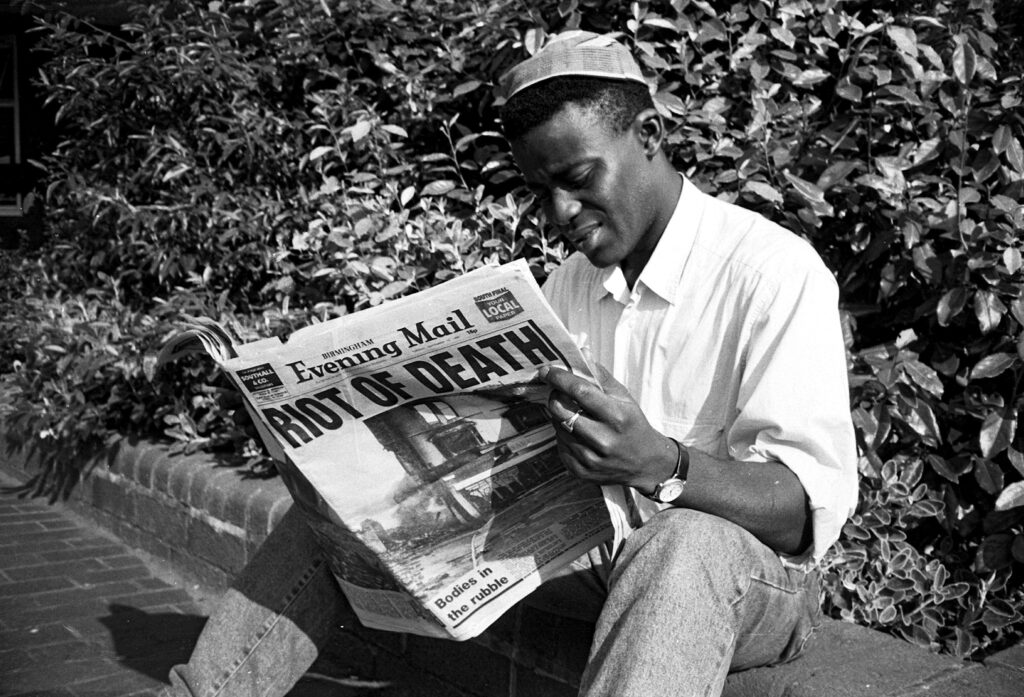

But one of the most powerful photographs in the film is that of a young Black man – in fact, it’s artist and film director John Akomfrah, who later took the riots as a subject for his own film ‘Handsworth Songs’ (1986). Sitting alone on a street corner, he reads the local newspaper, with the printed headline, ‘RIOT OF DEATH’. It’s one of many moments in the film which invites reflection from the audience.

An artist known for constructing visual metaphors, Caesar has framed the media’s sensationalist coverage of the riots within his own frame. He calls into question dominant narratives that have largely portrayed white-majority police forces as an essential tool to control ethnic minority communities in Birmingham, and beyond.

Commissioned by Birmingham Museums Trust, this film encourages new conversations about past events. As Co-CEO Sara Wajid says, “As well as referring to the sparking of the Handsworth Riots, ‘The Tiny Spark’ phrase could be a description of powerful artworks that can be tiny potent sparks for public debate and for our collective imagination and help us make sense of the times we are living in”.

In 2023, ‘The Tiny Spark’ offers a timely reminder that anger caused by neglect, poverty and racism can erupt into violence. In fact, Caesar’s photographs could have been taken just months ago, when protests swept across France following the police killing of Nahel Merzouk at a traffic stop. Images of unrest were shared widely across social media channels, accompanied by demands for change.

Caesar’s film undoubtedly carries forward conversations about anti-racism by “adding new layers” to the retelling of his story. Performing Zephaniah’s poems, which were written in response to Caesar’s images, are contemporary spoken word artists. “This is an angry young man, you should see him when he smiles”, says Chauntelle Madondo, addressing a balaclava-clad rioter, as she slows the pace to the sound of a drum. “But is it art?” asks Juice Aleem, cocking his head to the camera in a later frame.

‘The Tiny Spark’ is not just art, but art its most powerful. Almost 40 years on from the Handsworth Riots, Caesar has skilfully combined words and images to complicate reductive narratives that often make catchy headlines. Asking, once again, the question, “how could a tiny spark turn into such a gigantic flame?” he offers no answer but leaves viewers “to make up their own minds” as they watch this compelling new film. As spoken by Samiir Saunders, Zephaniah’s words ring loud and clear, “Dis is true news at ten me fren, Dere is a riot ina Handsworth again”.

This feature was originally published in the Birmingham Post and Mail.

The free-to-attend, immersive 16-minute premiere of ‘The Tiny Spark’ will be screened at Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum on Wednesday, 6 September. It will be followed by a Q&A discussion about Caesar’s work and the events of 1985.

Following the event, the film will be published on Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery’s website.

Further Reading:

A Brief History of Black British Art by Rianna Jade Parker (Tate, 2021)

Black Handsworth: Race in 1980s Britain by Kieran Connell (University of California Press, 2019)

13 Important Black Visual Artists Everyone Should Know (blog post)