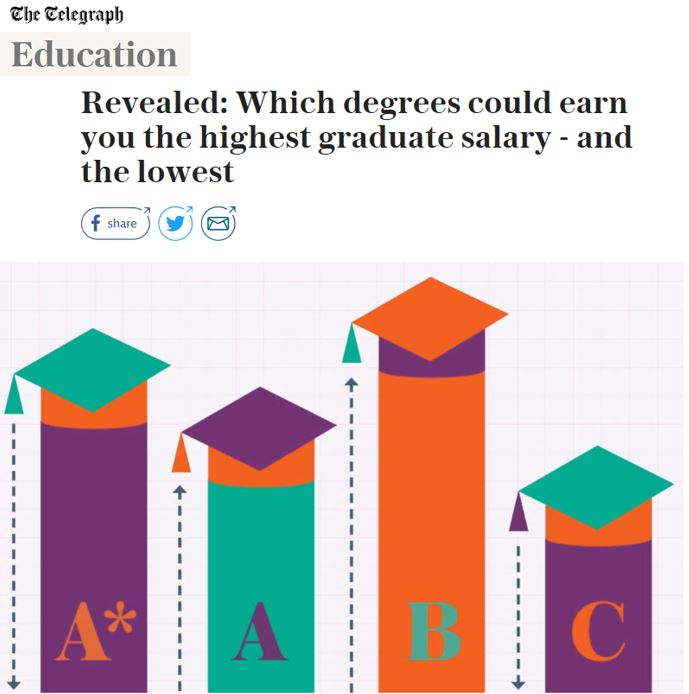

Last month the Telegraph published an article announcing, ‘Which degrees could earn you the highest graduate salary – and the lowest’. The media is full of headlines like this, reflecting a real shift in the dialogue surrounding university education and what comprises ‘value for money’. Nowadays, it feels like the focus is less on the quality of teaching than it is about earning an impressive graduate salary afterwards. It’s unsurprising, given that a degree will now set you back around £30k in tuition fees alone, that students and parents want to take this into consideration. But I’m not happy with the sustained focus on salary status post-graduation: it’s bad news for the arts.

The Office for Students and an ideological shift

Traditionally, one of the central beliefs of Higher Education policy in the UK has been that a university degree is valuable in its own right. That is changing. In January of this year the Office for Students (OfS) – a new, government-created regulator designed to champion the interests of student in higher education – came into effect. Their agenda is branded across their shiny new website: “We want every student to have a fulfilling experience of higher education that enriches their lives and careers”.

Today, a successful career is seen as one of the ultimate aims of a degree. And I have seen this first-hand with the students I have met, many seeking prestigious summer internships, and applying for Milkround graduate schemes throughout their final year. At times, it seems that they are focused on proving that their degree has been worth the investment to the extent that they struggle to make the most of their time in the classroom and on campus. It’s a hard balance to get right, especially when making high quality internship and job applications can take hours.

“Medicine has been revealed as the degree subject attracting the highest graduate salaries according to figures from the Department for Education. The statistics, which are drawn from PAYE and declared self-employment earnings data, show that the average medical graduate was earning £47,300 five years after completing their course….At the other end of the spectrum people graduating with creative arts degrees had the lowest average salaries, standing at just £20,200 five years after graduation…The figures are being released by the Department of Education as the government ramps up efforts to allow people to compare the value of studying different university courses” – Patrick Scott, The Telegraph.

Meet TEF, the Teaching Excellence Framework

This ideological focus on employability is deeply embedded in university life. Enter, the TEF, the Teaching Excellent Framework. Most lecturers shudder at the sound of it, and not because they are worried about the quality of their teaching. Not at all. You see, the TEF was set up by the government as a means of ‘monitoring and assessing the quality of teaching in England’s universities’. However, in reality teaching is just one tiny part of the TEF. Instead, much of the TEF is also based on graduate employability. To do well in the TEF, universities have to prove that their graduates go on to ‘graduate level’ jobs. So, employability is now a keen concern for universities wanting to rank highly in the TEF.

Entry into the arts

However, there’s a problem when you try to measure the employability success of arts students. You see, the TEF does not take into consideration the fact that many typical entry level arts jobs are not considered ‘graduate level’. If we take gallery work as an example, on the way to becoming a curator you might first have to work in arts administration or even as a gallery steward, building up experience. In the TEF stakes, this doesn’t cut it.

You don’t go into the arts for the money

And when you do make it into that ‘graduate level’ job in the arts, you’re probably not going to get paid a great deal. Many early career publishing roles pay national minimum wage, whilst even one of the top curators at the British Museum likely won’t make more than £40,000 per annum. In contrast, the Aldi Graduate Scheme offers its new starters a £42,000 salary, rising to £70,000 within four years (as well as an Audi A4 company car and private healthcare).

(The conversation around poor pay in the arts sector, making it inaccessible to many graduates, is one for another day).

My question is this: if you land yourself a place on Aldi’s lucrative scheme does it make your degree good value for money? The league tables seem to imply so. And so, if you start out as a gallery assistant, does this make your degree bad value for money? Is a well-paid job valued more highly than a poorly paid one? This focus on money makes me uncomfortable.

Career satisfaction vs salary

What these league tables don’t take into consideration is career satisfaction, and the extent to which you are actually using the skills which you have developed during your degree. For me, a great career has always meant doing a job I love, which allows me to put the skills, experience and knowledge I learnt through my degree, to work. I started on £15,000 a year in museum education, working on outreach art projects with youth groups. It was one of the most rewarding jobs I have ever had; I loved it. And I couldn’t have done it without studying Art History for 3 years, which made my degree extremely valuable. The league tables would argue otherwise.

Meanwhile, my flatmate was working 16 hours a day on a well-known graduate scheme, and was deeply unhappy. He couldn’t wait for the 2 years of training to be over.

De-valuing the arts

My concern is that if this narrative continues to place emphasis on high earning salaries as a sign that your degree was ‘worth the money’ then students will not choose to study the arts in the first place. Bear in mind that there are also sustained cuts to the arts, with many funding streams for museums and cultural organisations diminished, and school subjects like music and art being scrapped from the curriculum. I have already seen students choosing safer options that lead to vocations such as law or accountancy, over history or english.

Increasingly, will school leavers feel pressure to pick degrees and jobs based on earning potential over where their interests truly lie? While money is important, it’s an easy (and dare I say, lazy) measure of success.

Notable arts graduates

And I’m not saying you can’t make money in the arts, but success, to me, is much more than earning a salary with multiple 000s on the end. There are so many important cultural figures who chose the arts at university – Grayson Perry studied fine art, J K Rowling read Classics and French, Tate’s Director Maria Balshaw holds a BA in English Literature and Cultural Studies, and film director Danny Boyle is a Drama graduate.

Oh, and Patrick E Scott, who wrote the feature on graduate salaries for the Telegraph? He studied English Language and Literature.

Standing up for the arts

I hope that students, choosing between university courses, realise than an arts degree should be measured by more than graduate earnings. These league tables offer a very limited narrative, placing value on economics over the arts. And that makes me sad.

Ruth Millington is an arts graduate and art blogger, Tweeting all the latest art updates and sharing images on Instagram.