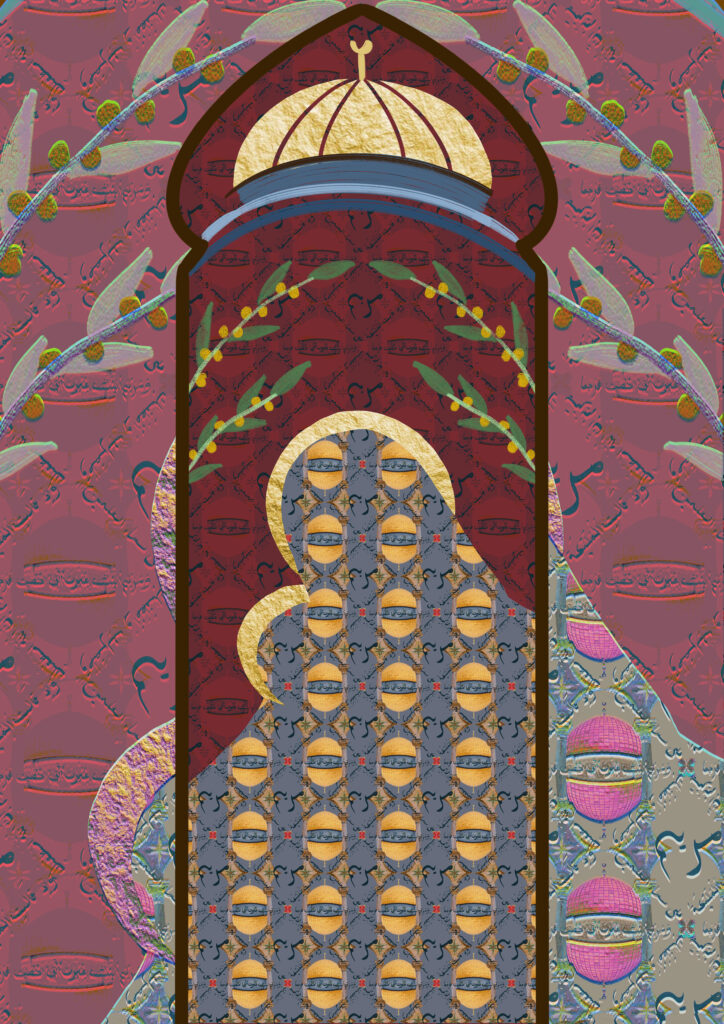

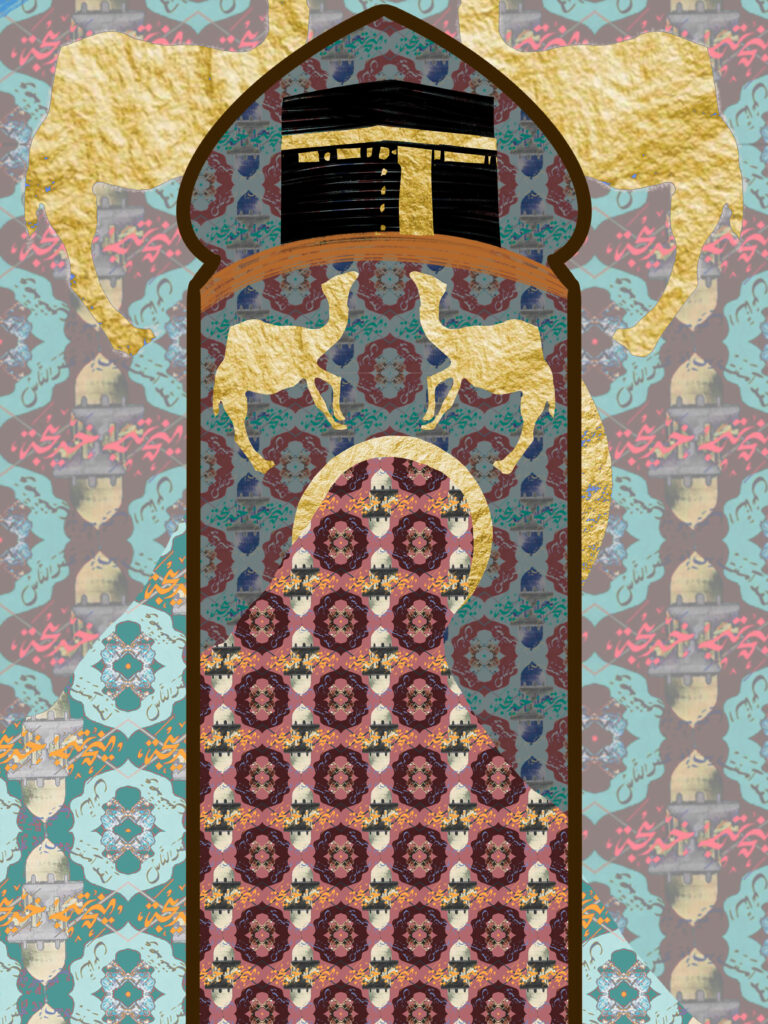

Four inspiring Muslim women have taken centre stage at Ikon, in an ornate installation ‘Women of Paradise’, 2022, by Farwa Moledina. These muses, appearing in silhouette form, either wear a burqa or a chador, decorated with intricate Islamic-inspired patterns. Each are framed by a wooden arch, in a nod to the mihrab, an arched nook that indicates the direction of prayer towards Mecca, found within a mosque. But this, of course, is not a mosque. It’s a contemporary art gallery, in which Moledina is clearly making a feminist intervention, to reclaim the narrative around Muslim women in art history, and wider culture.

Museums worldwide, from the Louvre to the Met, are filled with images of Muslim women, but many of these are problematic. Moledina has explained that her work deliberately “seeks to reclaim the exoticized narratives surrounding Muslim women”. As she has reflected, “Muslim women portrayed in galleries are, for the most part, depicted in Orientalist paintings. This means that they’re often shown to be idle, vacant beings whose existence serves solely to add further ornamentation to an already exotic backdrop”.

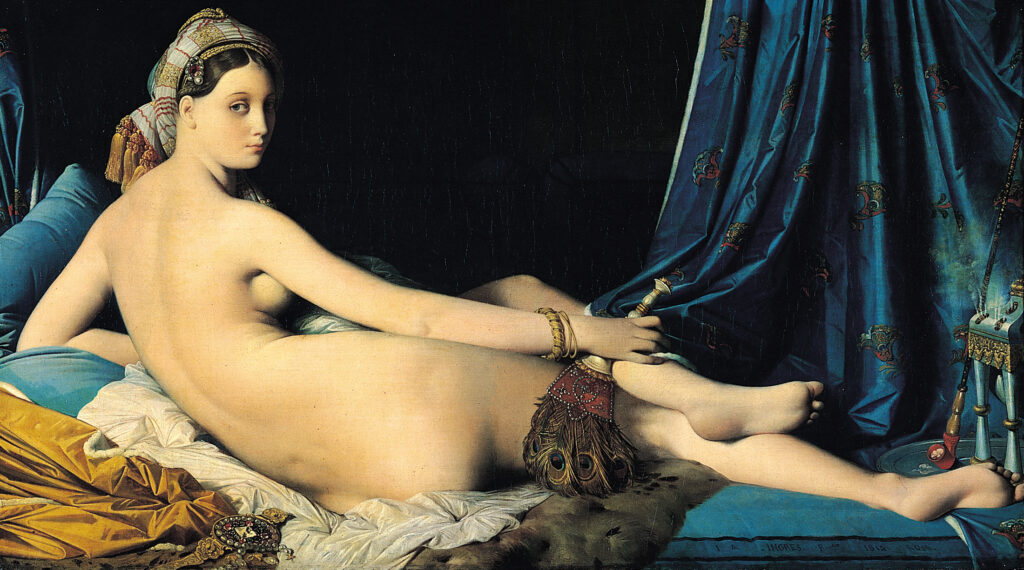

During the nineteenth century, European artists such as Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres and Jean-Léon Gérôme painted fantasies of Muslim women lazing in harems, wearing sumptuous robes and lying in suggestive poses. Most famously, ‘La Grande Odalisque’ (1814) by Ingres presents a reclining nude woman as an odalisque, or concubine; the artist has painted her wearing a colourful headscarf, appropriating this item of clothing to indicate that she is an exotic and erotic ‘other’ to be consumed.

As well as this traditional framing of the Muslim woman as an erotic ‘other’, within much Western contemporary art – and particularly photography – veiled females are frequently depicted as downtrodden, perpetuating a dominant victim narrative, within which Muslim women are always objects of oppression, curiosity and concern.

In contrast to this outsider’s gaze, which often misrepresents Muslim women, Moledina’s work, including this installation, “seeks to reclaim that narrative and the personhood of Muslim women.” For this artwork, Moledina was inspired by the four women named by the prophet Muhammad as the Women of Paradise: Khadijah bint Khuwaylid, Fātima bint Muhammad, Maryam bint Imran, and Asiya bint Muzahim.

She counts these women as “muses”, revealing:

“To me, a muse is someone that is inspiring, not in how they look physically, but in their personality and character. For me, these women are the perfect muse because of their strength and independence”.

Maryam mother of Isa, otherwise known as Mary, mother of Jesus, is considered one of the most righteous women in the Islamic religion. She is mentioned more in the Quran than in the entire New Testament and is also the only woman mentioned by name in the Quran.

The Mother of Islam, Khadijah bint Khuwaylid, was the first wife of the Prophet Muhammad, and is a shining example of a strong, independent Muslim woman with an entrepreneurial spirit.

Aasiyah bint Muzahim was, according to the Qur’an and Islamic tradition, the wife of Firoun (Pharaoh of the Exodus) and adoptive mother of Musa (Moses). She is revered by Muslims as one of the four greatest women of all time.

Fatimah Bint Muhammad, the daughter of the Prophet Muhammad and Khadijah, was known for her piety, kindness and humbleness. She, along with her husband Ali (as) cared for the needy, giving them food when they were already suffering from hunger. She inherited the great generosity of the Prophet (PBUH) as well as his eloquence, as she often moved people to tears when she spoke.

Situated in Ikon’s intimate Tower Room, these four women take up space with their presence. Chances are, you will witness this work, as I did, alone, with light falling upon the individuals represented in colourful patterns against simple, white walls. Allowing for a moment of private reflection, it’s the best use of the Tower Room that I have seen yet, so I wasn’t surprised to hear that the work had been designed specifically for this architectural site by the artist:

“When I first began thinking about this piece, I did have this space in mind. I find the Tower Room feels a bit like a prayer room, it has an almost sacred feel to it, and of course it is reminiscent of an ecclesial spire, and so I felt it would be perfect for this piece.”

This poignant interplay between private and public, intimate and open, is echoed in the clever use of silhouettes by Moledina, who plays on the notion of being seen and protecting the self. In contrast to her male counterparts, she ensures that these women are not here to be consumed. Moreover, she has considered Islamic sensibilities in the representation of her muses:

“Some Muslims are not comfortable with figurative work, I don’t find any issue with figurative work or portraiture, but wouldn’t feel comfortable depicting the faces of religious personalities. Therefore, out of respect, I chose to depict the four women in silhouette form. The silhouettes take the shape of veiled women, with Maryam’s taking inspiration from the typical composition of Mary and Jesus found within Christian religious paintings.”

Moreover, the silhouettes are cut out of patterns that Moledina specifically designed for each of the women, as a means of alluding to their individual identities. For instance, the pattern created for Aasiyah (a.s.) is made from drawings of rivers, pyramids, Moses baskets and narrations dedicated to her. “Each element of the pattern hints at the identity of the woman”.

The use of textile is an important aspect of Moledina’s practice, as crafts, traditionally dismissed by art historical narratives, are now being reclaimed by numerous women artists as a subversive medium for interrogation and protest.

For Moledina, her use and choice of patterned textiles is also highly symbolic, as they are “inspired by the Islamic design principles, such as those of symmetry, recurrence and abstraction. They are reminiscent of Islamic geometric patterns which often appear to be infinite. The main tenet of Islam is Divine Unity. The use of such pattern expresses the infinity and eternity of God.”

Moledina constructs her patterns by combining multiple elements, such as calligraphy or embroidery, with found images: “The designing of the pattern is a long process, I often create at least 30 iterations of each pattern before I’m finally happy with it. These are normally small changes that probably wouldn’t be noticeable to many, but the process is meditative to me.”

Moreover, Moledina’s patterns demand contemplation from her viewers, if they are to perceive the hidden depths and layers within each carefully crafted design which defines the woman’s silhouette. These layered patchwork pieces indicate that the veil is not alone in defining her Muslim muses’ identity, but belongs to a multifaceted whole.

With ‘Women of Paradise’, much like her wider body of work, including ‘Not Your Harem Girl’ and ‘No One is Neutral Here’, Moledina demands new ways of looking at women who wear the veil:

“Through this work, I hope that Muslims are able to view themselves and their histories represented in a gallery setting.

I also wish to encourage more critical thinking around museum and gallery displays, and to motivate viewers to reflect on their own prior notions of Islam, Muslim women, and what narratives they consider default (and why.) The audiences I have in mind therefore are both Muslim (women in particular) and also those that might not have a knowledge of Islamic tradition.”

She certainly achieves this with ‘Women of Paradise’, inviting viewers to reject reductive narratives about Muslim women, which art history has celebrated for too long. Instead, within the sacred Tower Room space, Farwa Moledina asks her audience to reflect and meditate slowly, on the complex identities of her inspiring Muslim women muses, seen afresh through her thoughtful, female gaze.

‘Women of Paradise’ can be viewed 13.11.22 at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham.

Limited edition prints of Farwa Moledina’s four Muslim muses are available from the shop.

You can read more about the representation of Muslim muses, symbolism of the veil and Orientalism in the chapter ‘Weaving a Way In’, in my book Muse.