Hundreds of china cats are currently sat inside Wolverhampton Art Gallery. Cabinets are filled with rows of porcelain feline figurines, of all shapes and sizes, ranging from sleek Siamese kittens to the orange comic book character, Garfield. The cutesy installation, ‘Cat-tharsis’ (2016/21), was created by Andy Holden and inspired by his late grandmother, who left him 300 china cats.

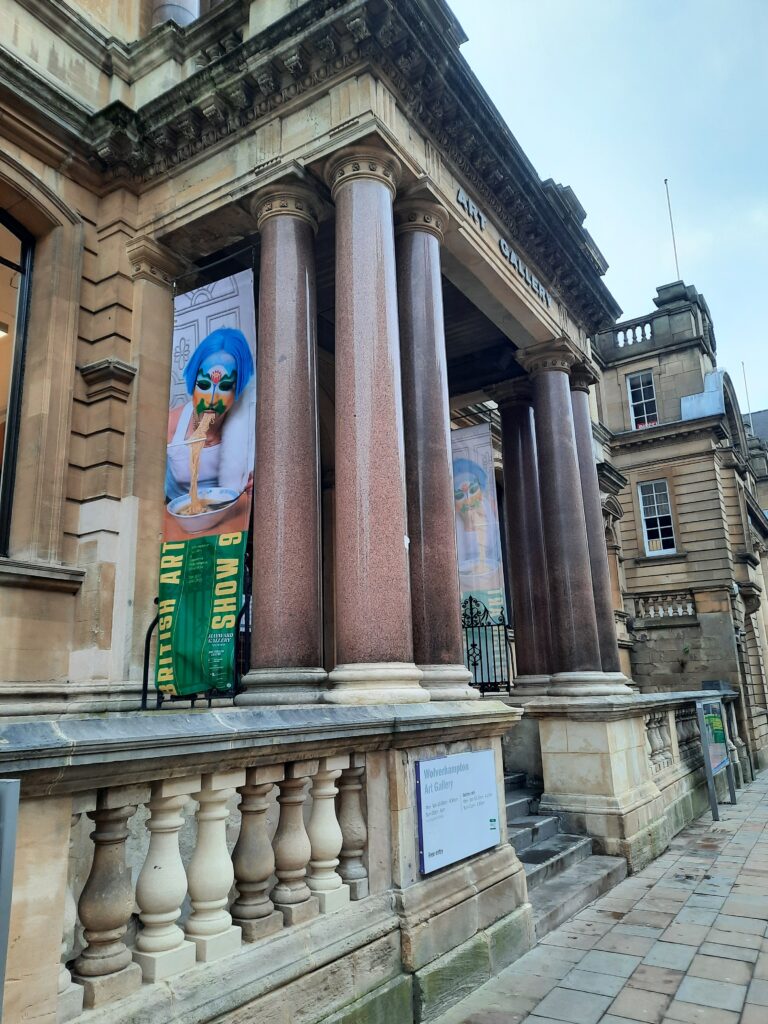

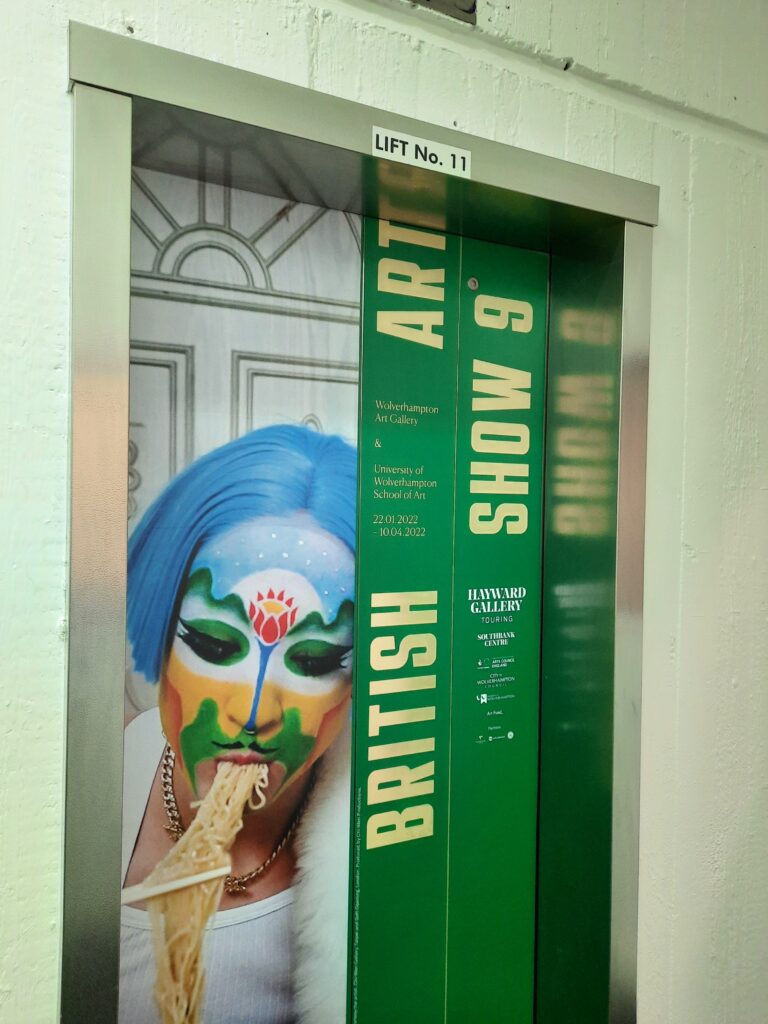

Holden is one of 34 artists who have work included in Wolverhampton’s iteration of British Art Show 9, which is being hosted across Wolverhampton Art Gallery and Wolverhampton School of Art. Having begun in 1979, this important Hayward Gallery Touring’s exhibition showcases the very best of Britain’s contemporary art every 5 years, or every 7 in the case of a pandemic.

British Art Show 9 has been curated by Irene Aristizábal and Hammad Nasar, who began their research with “no preconceived ideas” about what they would include. It’s a fair and admiral approach. “We visited 230 studios, in over 20 cities”, Nasar explains. Their one and only question: “What is exciting now?”.

Entering the first room at Wolverhampton Art Gallery, I have to admit that I felt less than excited to see a large ceramic sculpture by Florence Peake oozing across the floor. It appeared dated (pointing to the problem with finally staging a contemporary art show, which had been put on hold for several years; the works were selected pre-pandemic). Around the Gallery, there were also casts of severed animal heads, laid on their sides – again, they came across meaninglessly performative, rather than beautifully absurdist.

I’m not the greatest fan of video art (or sorry, ‘moving image’), and there is a lot of it included in this show. Much of it came across as self-indulgent reflections on identity, although there are nice beanbags – rather than the usual cold benches – to watch it from. You’d need half a day to watch the hours of footage: there are over 5 hours in one black box, which is not exactly conducive to moving between artists in a group show.

The show also seemed disconnected, jumping from a room of Holden’s cute cats to Uriel Orlow’s research project on malaria (which Jonathan Jones has taken real issue with) to an installation of colourful protest placards and costumes, titled ‘Plant Theatre for Plant People’, by Grace Ndiritu who has been living in alternative communities in LA. ‘Where is the connection and dialogue between these artists’?, I began to wonder.

There are some threads woven throughout; the curators had decided to “distil” what they had discovered during their research trips into 3 main themes: Healing, Care and Reparative History; Tactics for Togetherness and Imagining New Futures. I am not sure that this is entirely evident as you walk around, especially if you haven’t read the press release. I also felt that much of the work couldn’t quite be contained within one of these (slightly forced) structures.

But, where the show does excel is in its critical conversations with Wolverhampton’s own cultural history. I love the fact that the curators had decided to adapt the show for each of the 4 cities it would be exhibited in, taking into consideration local contexts. In Wolverhampton, known for its super-diverse population, the exhibition has a decided focus on how we live with and give voice to difference.

The city was also home to the British Black Arts movement – many of its members studied at Wolverhampton School of Art – so, I was thrilled to see work by Eddie Chambers, Hurvin Anderson, Barbara Walker and Sonia Boyce included. During the 1980s, these artists began to explore the intersection of gender, class and race in their radical, politically charged practice.

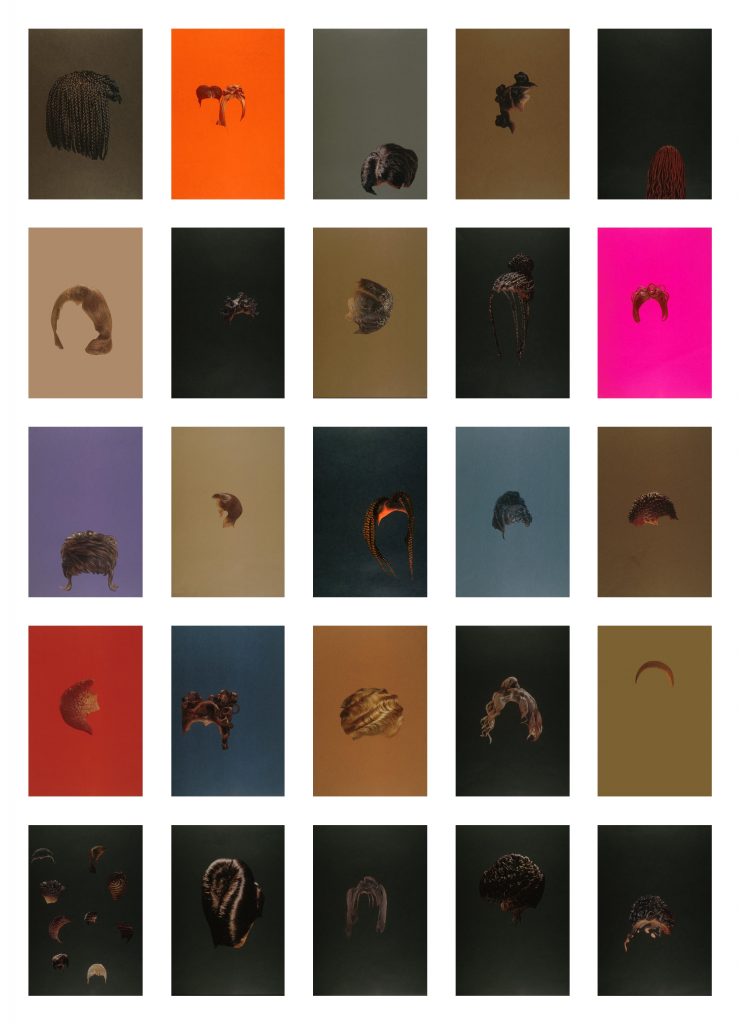

A highlight is the powerful collage ‘Black Female Hairstyles’ (1995) by Sonia Boyce, which explores the politicisation of natural Afro hair, and how Western beauty standards have led to the continued discrimination against Black people in the UK.

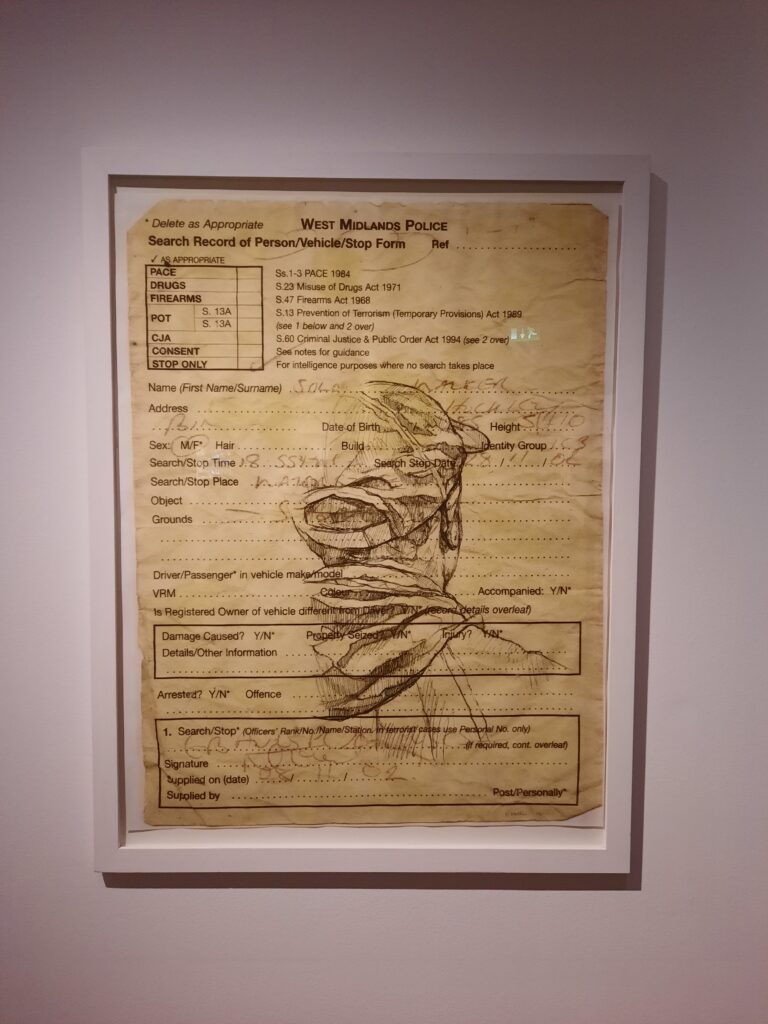

In the same room is Barbara Walker’s ‘I can Paint a Picture with a Pin’ (2006). She has overprinted a West Midlands police Stop and Search form with an image of the back of a young Black man’s head. The details on the form are those of her son, who had been stopped and searched numerous times. She has not only pointed to disproportionate use of stop and search powers against young Black men, but also given a name to the statistic. Now, this is the work that hits home the hardest, feeling more relevant than ever.

From here, the show only gets better, especially across the road at Wolverhampton School of Art. This is where the exhibition is immersive, more contemporary and, emerges as truly exciting.

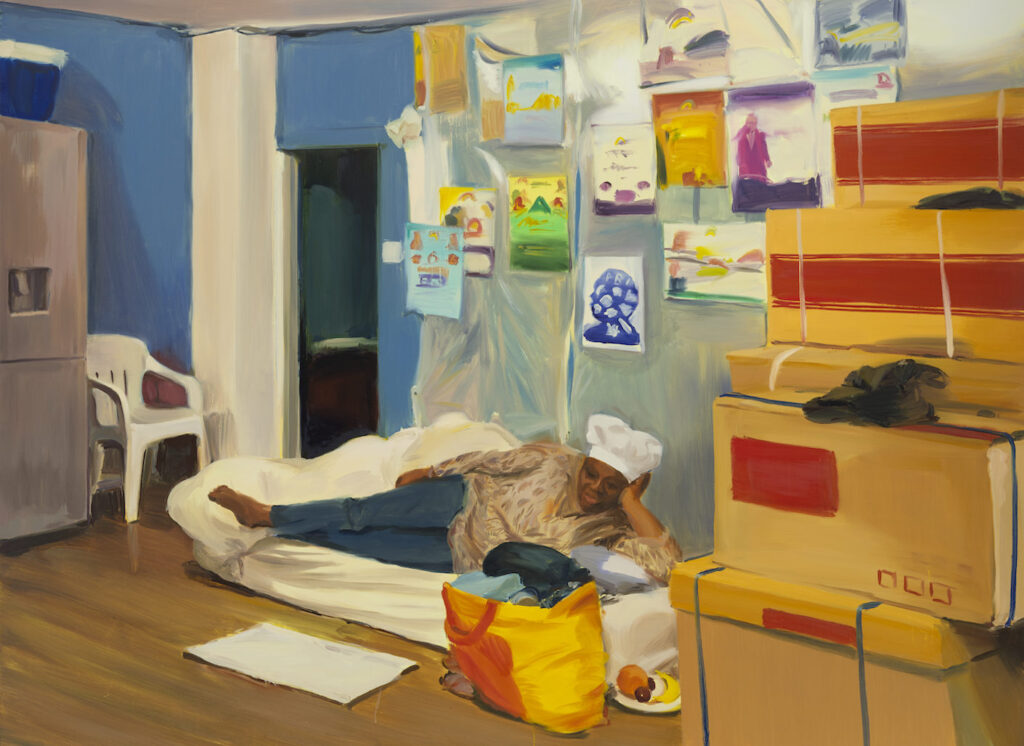

Highlights hanging in the art school include Caroline Walker’s lustrous paintings of female asylum seekers stuck inside temporary accommodation, lost in an unseen limbo. They wait in hostels and shelters, a psychiatric ward and a church basement – Walker deliberately opens the viewer’s eyes to their stories.

In the same space, Oscar Murillo’s new site-specific installation of blackened canvases hang from the ceiling, offering a glimmer of hope, presenting the idea of seeds flourishing in darkness, and (given the location) presenting art schools as spaces for daring interventions and progress.

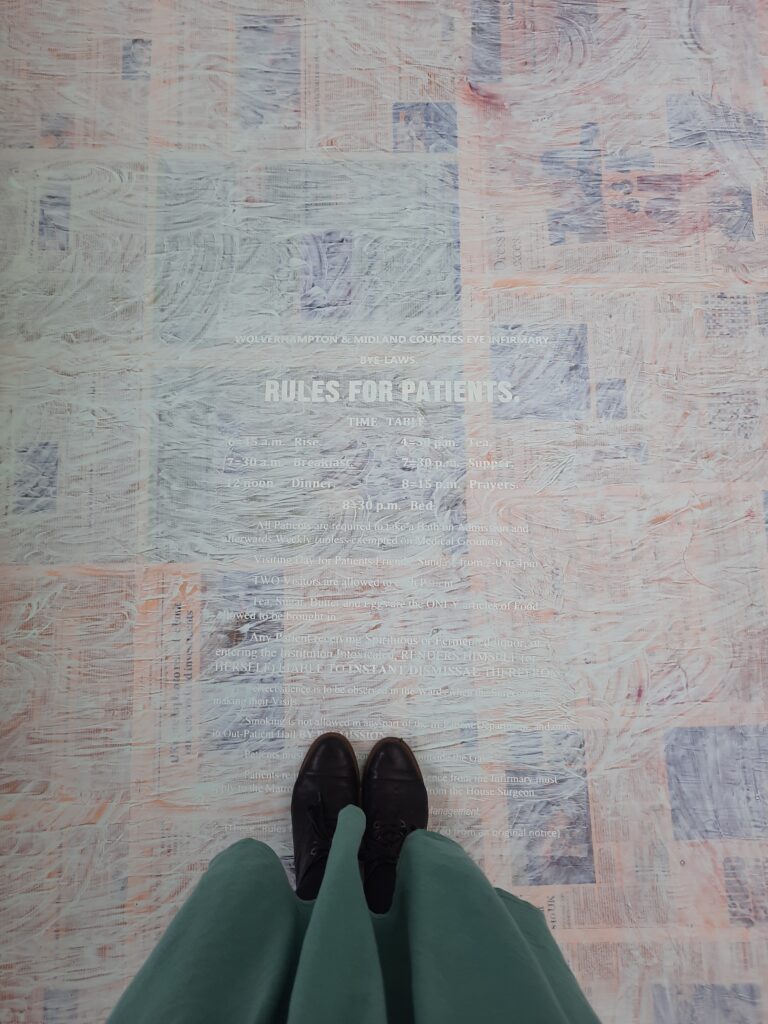

Meanwhile, Mandy El-Sayegh’s unnerving installation, ‘Blank Verse Blanket Man’ covers the walls of one room with copies of newspapers and hospital green paint, pointing to the act of a ‘dirty protest’. The artist was inspired by both local Wolverhampton poet Alfred Noyes, who wrote about France Drake, and political prisoners. As she has explained:

“In particular, it will be the smeared cell of excrement of a prisoner who doesn’t have a name, so it looks at the themes of the show for invisible subjects and voices and brings them together.”

Meaning become more loaded when it’s layered. And it’s these layers – from past to present, local and national, spanning and crossing gender, race and religion – which make for a rich British Art Show 9.

Before I leave the exhibition, I return to Holden’s kitsch kitties – this installation reflects the human desire, and need, to collect, order and categorise. But life, with its complexities, is hard to contain and structure into ordered subjects. The same goes for art – as becomes far too clear across this show, which feels somewhat disjointed at times. The 3 constructed themes don’t work particularly well, particularly when the best works on show elude such simple categorisation.

But, there is one consistent message which does emerge across both venues: great art can give shine a spotlight on the unseen and voice to the untold, including local people and their narratives. This national touring show has taken into consideration Wolverhampton’s own diverse and creative history, giving this city the attention it so deserves.

Moreover, the superb staging in Wolverhampton School of Art – which feels fresh, full of vitality and current – also demonstrates that it is in art schools where some of the most important, socially engaged and courageous conversations are happening today. We must continue to champion our creatives working across Britain – in fact, we need them more than ever, as they continue the work of their predecessors.

Kudos to the curators and all artists involved: at its best, British Art Show 9 is an immersive and eclectic exhibition, which demonstrates that the best contemporary art begins, and extends, beyond the carefully curated walls of the gallery. Engaging with Wolverhampton’s own radical art history, this is an invigorating and exciting exhibition which gives a celebratory voice to difference.

One thought on “Review | British Art Show 9 in Wolverhampton”