Birmingham was once home to the strangest of all modern art movements, Surrealism. It was in the Trocadero pub – still serving pints on Temple Street today – that Emmy Bridgwater, Conroy Maddox, Oscar Mellor, John Melville and Desmond Morris would meet up. These five artists were some of the most important, and outrageous, members of the group. But their names are largely unknown – because they chose to live and work locally, rather than moving to London.

London has always been seen as the centre of Britain’s art world, when creative talent can be found across the UK. Regional cities have long been overlooked, as reflected in Arts Council England spending of £21 a head in the capital, compared to an average of £6 a head in the rest of the country. In 2022, the government announced its plans to reduce such inequalities through the Levelling Up agenda, with an aim “to make sure that people feel enormous pride in the places that they call home”. What better way to do this than to ‘level-up’ local art history, starting with Birmingham Surrealism?

Founded in Paris by André Breton, Surrealism is associated most of all with Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, who pictured the unconscious with dreamy paintings of cloud-filled eyes and melting clocks. But in 1936 it officially arrived in Britain, with the International Surrealist Exhibition in London. Artists from Paris were showcased alongside their British counterparts, including Henry Moore. However, none of the Birmingham Surrealists exhibited; in fact, they refused to take part, and with good reason.

From the beginning, Birmingham’s artists saw themselves as opposed to the London group, believing that many of these artists involved in the movement just for exposure. Morris says: “There was a popular preconception that just because Birmingham was the second city and London was the first, the art of the latter had to be more significant than the art of the former. Because of this illogical notion, we tried harder – we wanted to show not only that we too were Surrealists, but also that we were truer to the ideals of the movement”.

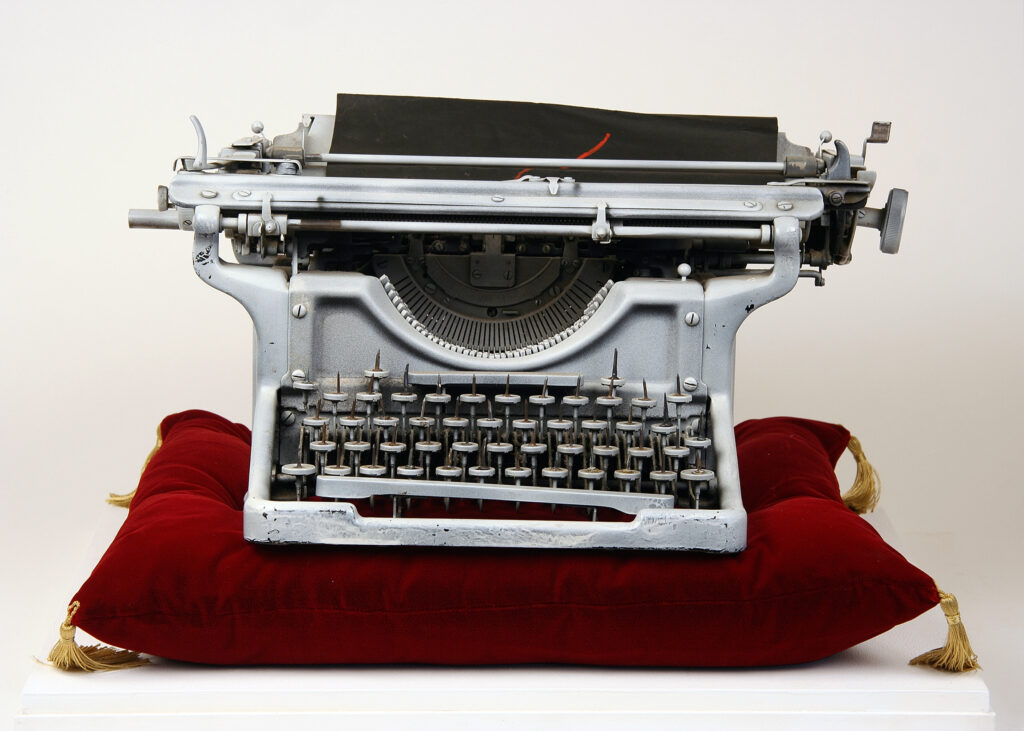

In fact, one year before the exhibition, British Surrealism had already begun in Birmingham. Ring-leader Maddox joined forces with Melville, and then Mellor and Bridgwater, to shake up the city’s art scene, and shake it up they did. Maddox transformed ordinary objects into surreal sculptures, sticking spikes to the keyboard of a typewriter, and staged scandalous photos in which he was naked and accompanied by a drunk nun; the council put a stop to his plans to enact these scenes in shop windows.

Meanwhile, Bridgwater made paintings and wrote poetry populated by strange birds, eggs, and swirling lines. Impressed, Breton wrote: “Bridgwater brought a new purity of outlook to British Surrealism”. Forging links directly with France, Birmingham’s Surrealists exhibited in Paris and were invited by Breton to sign new manifestoes.

Back in Balsall Heath, Maddox hosted parties at his huge 11-bedroom home. Among the guests were dancers, singers, and students from the University of Birmingham. It was through these gatherings that Morris, then a zoology student, joined the movement. He painted canvases, such as ‘The Jumping Three’, 1949, featuring imaginary “biomorphs”. Police were also called to investigate one of his surrealist stunts, when he appeared to have planted “a dinosaur in Broad Street”, as this newspaper announced. It turned out to be an elephant’s skull, discarded by his academic department, but in Morris’ hands it became shocking installation art.

It’s clear that British Surrealism’s most radical members didn’t just survive, but thrived, in Birmingham. In fact, the city has always been home to great artists, including the early Impressionist David Cox, leading Pre-Raphaelite Edward Burne-Jones, Arts and Crafts designer Georgie Gaskin and photorealist painter John Salt.

Yet, dominant narratives in books, exhibitions and documentaries have often side-lined such artists, denying them the attention they deserve. It’s a travesty, as art created beyond the capital is often more subversive and inventive than that produced within London. Contemporary art in Birmingham continues to prove this point, with the city and its people inspiring photographer Vanley Burke, Turner Prize-shortlisted Barbara Walker, and Cold War Steve, who inserts significant historical figures into satirical collages. As he says:

“I’m very proud of Birmingham’s art history, which, in typical Brummie self-deprecation, never seems to be boasted about. I particularly admire the Birmingham Surrealists’ dismissal of their London contemporaries, who we’d now call ‘too metropolitan elite’. There remains, I feel, a genuine authenticity and freedom, for an artist to live and create work outside of the capital, free from the foreboding influence of the bourgeois art establishment”.

With a wealth of regional talent, we must all take pride in the cities and suburbs beyond the capital, where some of art’s greatest stories can be found. Art history needs ‘levelling up’ and Birmingham Surrealism is just the start.

This text was originally published as an op-ed in the Birmingham Post

Really enjoyable article and I also very much enjoyed the Radio 4 programme. Are you intending to give any talks about the Birmingham Surrealists?

I am giving two talks but they are sold out, so I will have to organise some more!

Please do! I really enjoyed the Radio 4 documentary and your article!