This year, I moved back to Birmingham, and what a year I chose. I’ve been reflecting on the highs of 2023, as well as its lows: Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery has been closed for major renovation works, the Council declared bankruptcy (with significant ramifications for the creative sector) and, just weeks ago, the inimitable poet and writer Benjamin Zephaniah sadly passed away.

The outpouring of love for Zephaniah has been overwhelming – proof that this Brummie touched so many people. What a great loss for the city. But his words will live on, as the first of my 2023 highlights proves.

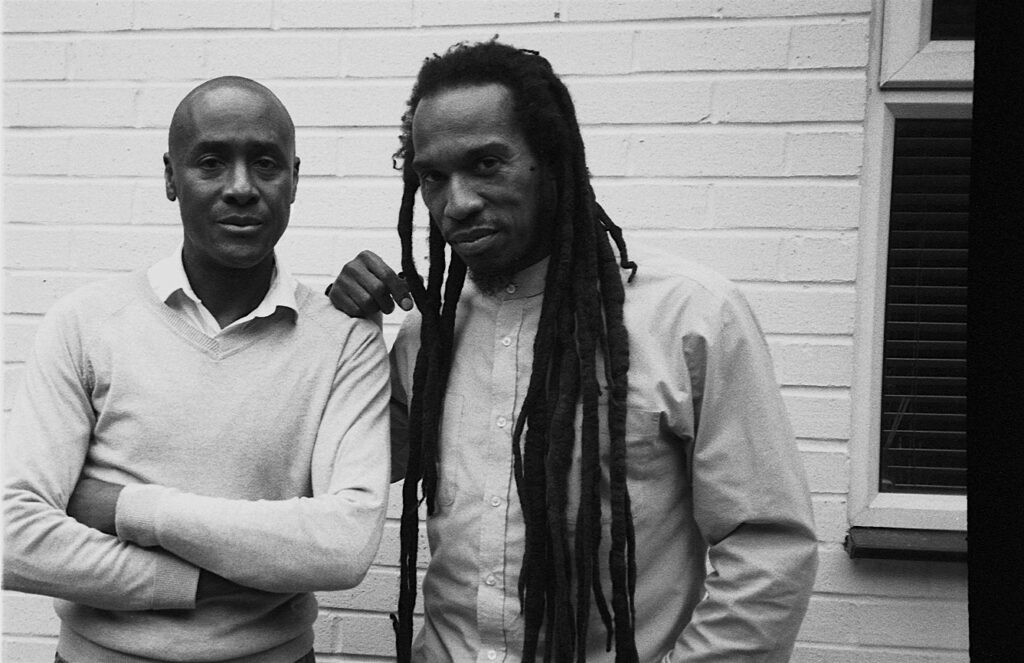

In the summer, I reviewed ‘The Tiny Spark’, which Zephaniah created in collaboration with Pogus Caesar. The powerful film reframes the Handsworth Riots, which took place almost 40 years ago, with Caesar’s striking black and white photographs of the traumatic event accompanied by the poet’s words, spoken by contemporary performers.

“This is an angry young man, you should see him when he smiles” – Zephaniah’s line breathes humanity into a balaclava-clad rioter who appears on screen. Words and images combine to complicate reductive narratives that often make catchy headlines. Instead, viewers are offered another view of Birmingham’s history.

Birmingham’s history is too often misrepresented or forgotten, and another 2023 highlight was sharing the story of the city’s Surrealists, who have been largely erased from mainstream narratives. Walking the streets with comedian Stewart Lee, we uncovered their tales, stunts and Surrealist masterpieces for BBC R4. From Five Ways to the Trocadero pub and Balsall Heath, we followed in the footsteps of Birmingham’s most radical artists, one of whom left ‘a Dinosaur in Broad Street’, or so this newspaper reported in 1949.

I also took the story of Birmingham’s Surrealism to the top of the Rotunda, where Staying Cool have been hosting Creative Heights, an engaging year-long programme of painting and drawing sessions, literature talks, and open house photography sessions, set against the city’s skyline.

Back on the ground, contemporary Birmingham artists have made history, too. A month ago, I got chatting to a man leaving the Library of Birmingham. Revealing that he was once a local art teacher, as we awaited a tram, I asked who his best student was. “She’s nominated for the Turner Prize”, he told me. “Barbara Walker?”. “Yes”! One of 4 artists selected for the prestigious and often controversial prize, Walker has drawn poignant Windrush scandal portraits directly onto Towner Eastbourne’s walls.

Back in her home city, Walker also generously gave her time to judge over 120 artworks in the inaugural Drawing Prize at the RBSA Gallery. In the contemporary art world, drawing has become an overlooked practice but the RBSA made quite the statement with this year’s show, inviting viewers to appreciate the diversity of approaches and rather radical act of drawing in our fast-paced world where shareable images dominate online galleries.

It was Curtis Holder, highly commended for his portrait ‘The Jewellery Maker’, who told me: “Drawing is shy – it doesn’t shout, it’s a conversation. You need to stand in front of it and see it in person.”

Those words have stuck with me, as I’ve viewed hundreds of artworks in person this year. Particularly memorable have been the evocative landscape paintings of Annette Pugh at the New Art Gallery Walsall, Paul Lemmon’s kaleidoscopic mural of deconstructed digital images, titled ‘Memories of a Future City’, at the Coventry Biennial, and a painted storm in a teacup by Paul Newman in ‘Worlds Away’ at Midlands Arts Centre. I also loved seeing the doodles, drawings and textiles of Madge Gill, who used art as a form of therapy, in her major and inspiring retrospective at MAC.

‘Makers and Machines’ at Thinktank Museum was another stand-out show for me. I like to be surprised by an exhibition, and this thoughtful, clever curation had exactly that impact as I viewed contemporary art alongside historic objects, in an exploration of the connections between creativity and science, AI and traditional weaving, by the likes of Arts and Crafts pioneer William Morris.

However, I experienced my greatest moment of wonder not in a gallery but, instead, stood in Birmingham Cathedral. It is home to four of the finest stained-glass windows in the world, which have now been restored to their former glory, thanks to a grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund. In time for Christmas, panels of pink and gold, rich reds and cobalt blue glow as sunlight shines through the windows, illuminating crowds of angels, sheep, Christ and Mary – all designed by Edward Burne-Jones.

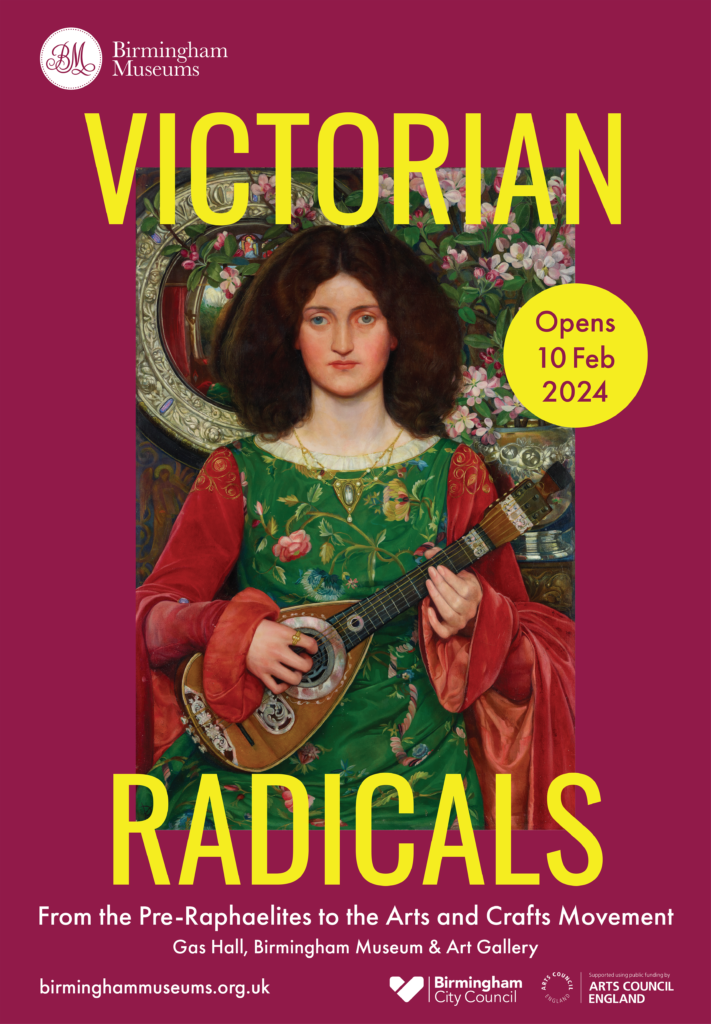

Burne-Jones will also be making a return to Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in February 2024, when the Gas Hall will reopen with a major exhibition celebrating the city’s ‘Victorian Radicals’, including Kate Bunce, Joseph Southall and Arthur Gaskin. Looking back and ahead, from the late Benjamin Zephaniah to Barbara Walker, it’s the city’s radical artists and their legacy which makes Birmingham a place to be immensely proud of, and I’m happy to be back home writing about them.