The Coventry Biennial is back, and it’s more imaginative than ever. Titled ‘… like a short cut through the brambles’ and featuring 15 artists across 5 spaces, it investigates our relationship to nature and addresses an issue on the wider art world’s mind: climate change. But, what role should artists and curators assume in changing conversations around this global problem?

I start at the Old Grammar School, where Mothers Who Make Coventry have grown a garden from scratch. A peaceful space in the city centre, it also celebrates the collective effort of local mothers who are makers. A quietly important intervention, this flowering patch makes connections between motherhood, creativity and nature.

It also offers a direct rebuttal to the norm of shipping giant artworks across oceans, and most famously to the sinking city of Venice, for temporary Biennials. As participating artist Adele Mary Reed points out:

“Art often centres around “stuff” and materials. There’s endless more work that could be done around monitoring and adjusting where these materials come from and what happens to them afterwards. People rarely take account for what they consume and discard and artists, galleries and biennials are no different.”

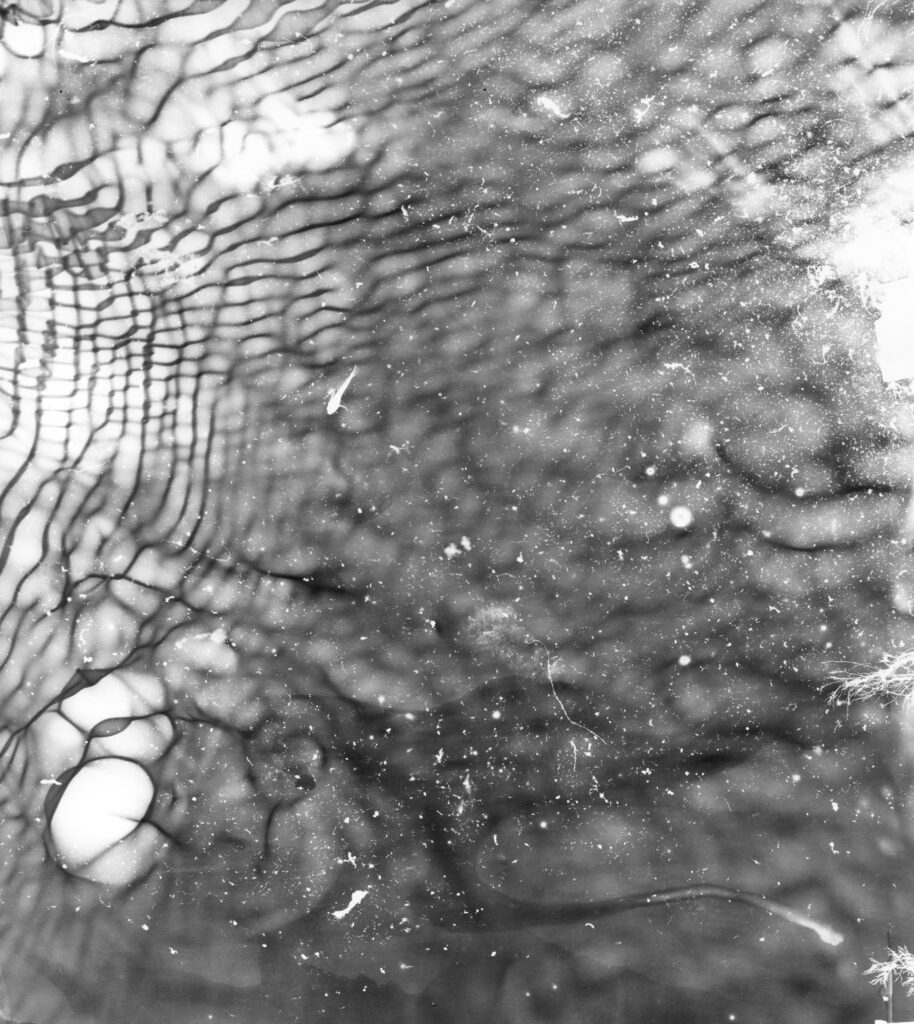

Instead, this locally-grown garden of humble British plants shows what can be done from just a few seeds. The same consideration towards the environment is reflected in Jo Gane’s photograms – using historic techniques, she has carefully captured the abstracted flow patterns of the River Sherbourne as it passes through Coventry, carrying with it objects, including a fish. Framing the water’s ever-changing routes, she invites wonder at the world’s forces.

Exhibited in the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, Gane’s photograms exist in dialogue with water-themed work by other local and international artists. Silver-dipped shells sit on the bed of Alice Channer’s huge, pleated sculpture, ‘Soft Sediment Deformation’, its earthy colours evoking a rock formation. Growing from the wall opposite are her silver bramble sculptures, as if pointing to the resilience of nature which has reclaimed this space.

Water also ripples through the hand-dyed, woven textiles made by members of the Ikon Youth Progamme in collaboration with Seungwon Jung and volunteers from The Weaver’s House, to explore Coventry’s history of weaving. Working from Ikon’s Slow Boat, a converted narrowboat, these young artists are intrinsically connected to nature. As Programme Coordinator Rosie Abbey says:

“The routes, viewpoints, and movements of the boat offers the group a unique perspective of the natural environment within and just outside of the city. This project with Seungwon has allowed us to consider these small moments (of light, water and natural materials) and their relationship to the climate.”

Their woven patterns of collaboration are uplifting, and echoed in an epic painting, ‘Memories of a Future City’, which stretches 20ft across one wall. A kaleidoscopic landscape of tessellated shapes, it was created by Birmingham-born artist, Paul Lemmon. As if foraging through cyberspace, he collects and deconstructs screenshots of digital images.

“Just like in the natural world where material is broken down and grows into new things, I’m following that process by breaking down what I find in the digital forest and transforming it, growing it into a physical thing, a painting”, he explains.

Evolving from earthy greens to brighter hues, the abstracted, map-like painting carries a deeper message. Created in partnership with Professor Graeme Macdonald, it includes an imaginary timeline to 2123, which charts potential events, such as the city being declared fossil-free in 2072.

When so much climate change-centred art is apocalyptic, Lemmon’s positive view offers a refreshing new vision. It also contrasts with the aggressive tactics of Don’t Stop Oil, who deliberately attack artworks in major museums; while they gain headlines, they also alienate huge numbers of people; isn’t this a more productive way of gaining support for green policies?

Lemmon does, however, find the idea of responsibility falling upon artists “problematic, because it’s a bit of a utilitarian approach and shouldn’t be a requirement.” Art shouldn’t need to have a specific purpose or impact. But, as he recognises, “Biennials perhaps have the most responsibility, in that the sheer size and weight of what they bring together can amplify ideas.”

Before leaving the museum, I take the stairs down to the medieval undercroft, where artist duo A History of Frogs have imagined an alternative universe: uncanny, spindly sculptures carry bathos in their dark ‘Goblin City’. It’s a curious and amusing end to my visit; this Biennial recognises its responsibility to the environment, but wears it lightly, thankfully.

Without preaching, the curators of this absorbing 4th Coventry Biennial have successfully cultivated a show of creativity embedded in the care of nature, while sharing nuanced messages of hope that we might all have more appreciation for life on earth. After all, as Lemmon says, “it’s the greatest masterpiece of all”.

Coventry Biennial 2023 takes place across Coventry and Warwickshire until 14 January 2024.