Rediscovered Birmingham Surrealist Emmy Bridgwater is finally getting recognition, with a solo show at London’s Mayor Gallery, titled ‘The Edge of Beyond’. It was an honour and privilege to write an essay for the catalogue, which I am sharing an extract of here.

Emmy Bridgwater: A Surrealist State of Mind

On 11 June 1936, the International Surrealist Exhibition opened in London. Huge crowds brought Piccadilly’s traffic to a standstill. Visitors were both awed and baffled as Dylan Thomas offered around teacups of boiled string, Salvador Dalí delivered a lecture while wearing a full deep-sea diving suit, and Sheila Legge strutted through the show dressed as The Phantom of Sex Appeal, carrying a prosthetic leg. None was more impacted by this dramatic arrival of Surrealism in Britain than a 30-year-old artist and poet from Birmingham: Emma ‘Emmy’ Bridgwater.

Born in Edgbaston, Bridgwater began formal art education at the progressive Birmingham School of Art, which had a history of welcoming women artists. Here, she became a skilled painter and draughtswoman. But it was the Surrealist exhibition that Bridgwater regarded as “quite a revelation”. Here, she crucially met fellow artists Conroy Maddox and John Melville, and the writer Robert Melville. These three men, all from her home city, were already committed to Surrealism. Having found artistic allies, Bridgwater worked with them to establish the Birmingham Surrealist Group, which was later joined by the younger artists Oscar Mellor and Desmond Morris.

Bridgwater was a leading member of this ambitious circle of artists and writers. Throughout the 1930s and 40s, they acted as a unified collective, organising lectures and debates, to which they also invited Birmingham-based academics and musicians, while working individually on their own Surrealist visions, each developing a unique style.

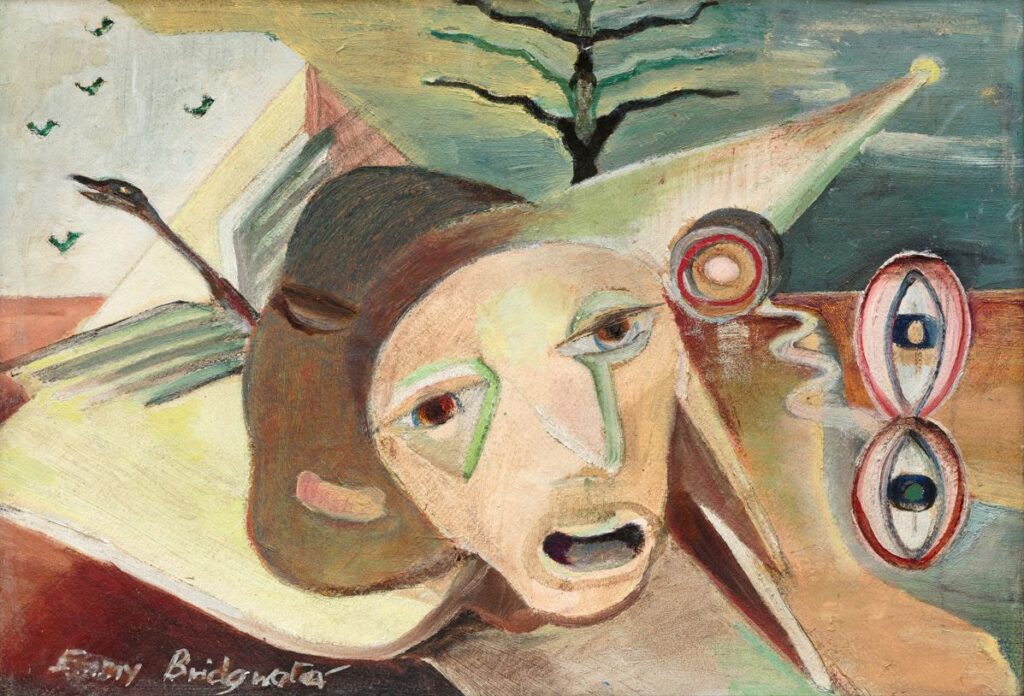

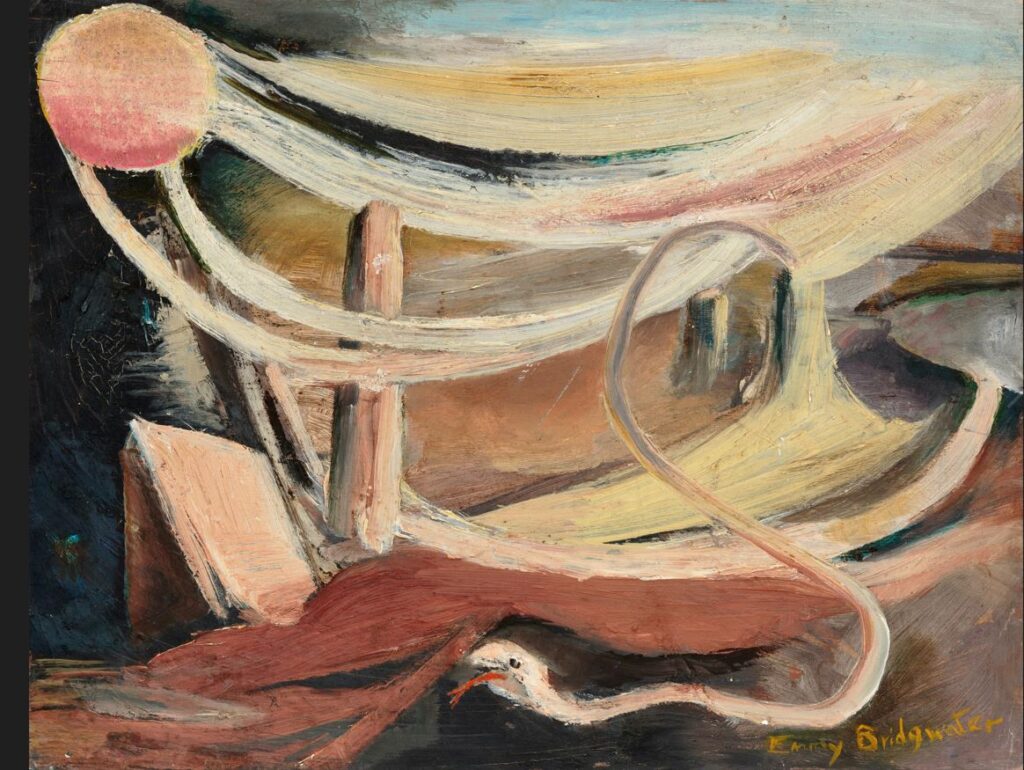

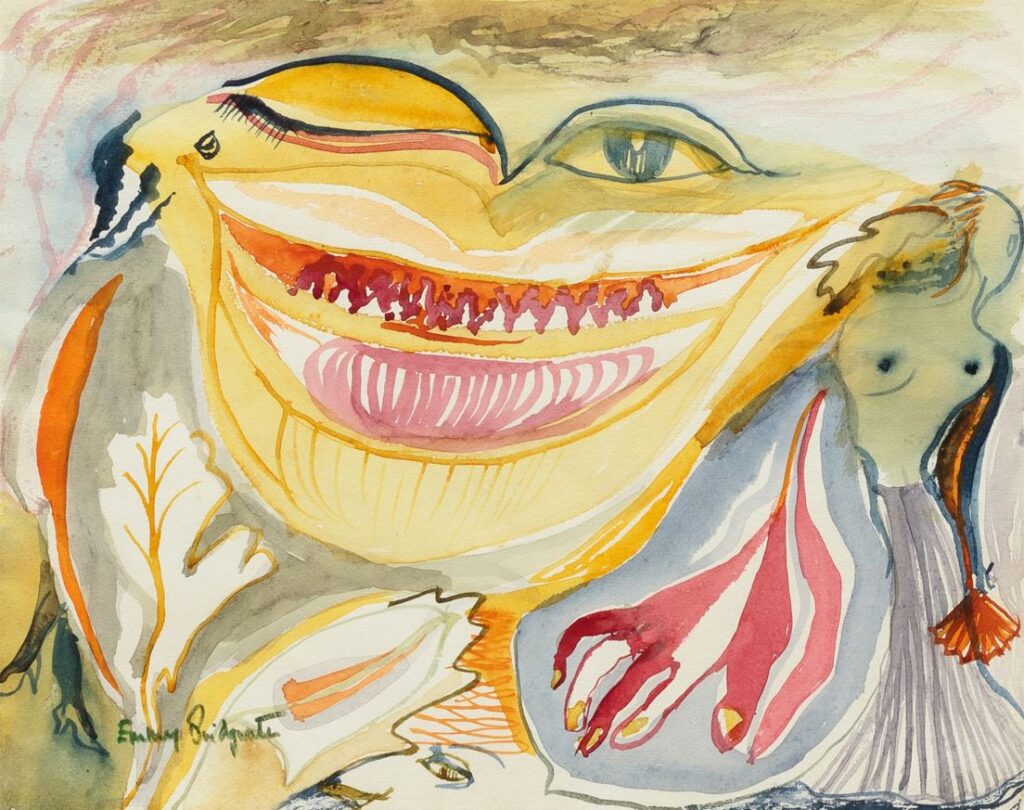

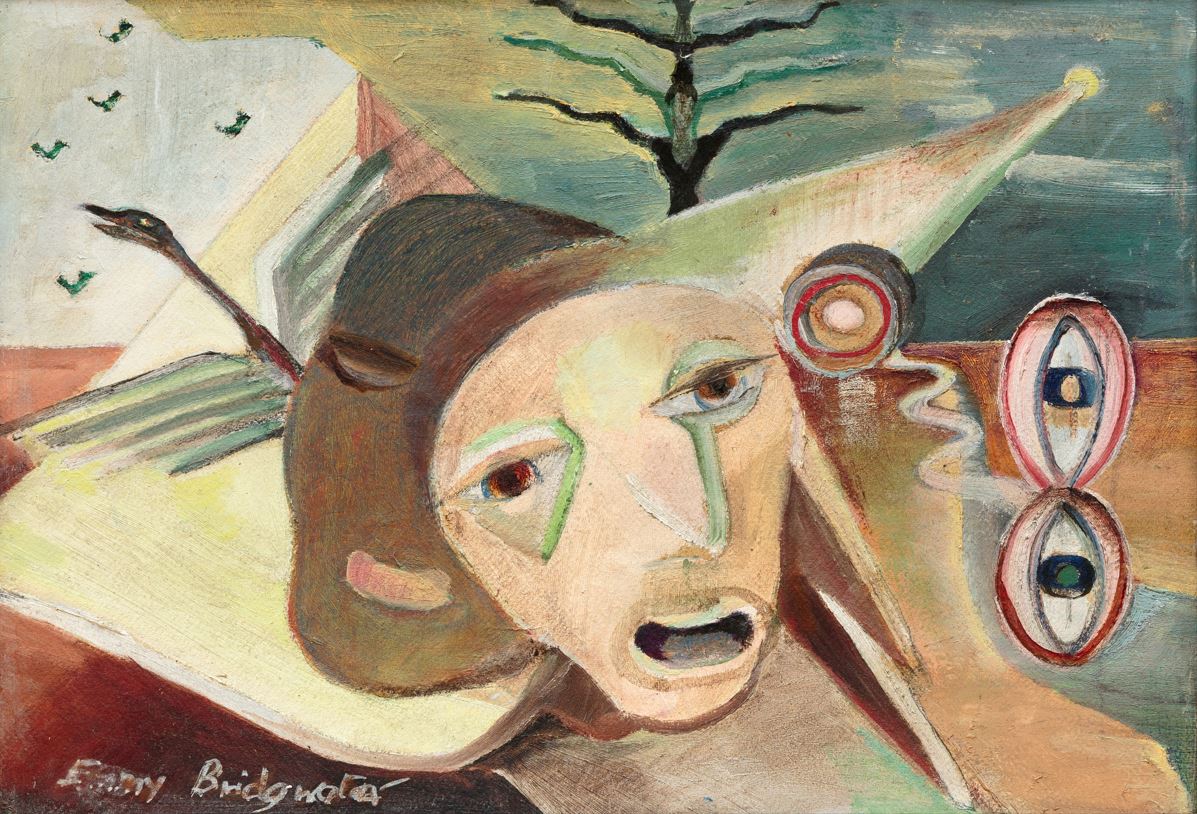

During this period, Bridgwater invoked the Surrealist principle of juxtaposing unusual objects to reveal uncanny narratives; in her paintings and ink drawings viewers are invited into interior worlds, defined by a symbolic language of birds, eggs and organic forms.

From the outset, these Birmingham artists were distinguished by their opposition to a London-based vision of Surrealism, which they saw as inauthentic or even anti-Surrealist. Often overlooked and side-lined by art history’s narratives, these Surrealists of the ‘second city’ not only separated themselves from the London-based members but were determined to make art that was more revolutionary, more scandalous and ultimately more surreal, than that of their southern rivals.

In his founding 1924 Manifesto of Surrealism, Breton had defined Surrealism as: “Pure psychic automatism … the dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason and outside all moral or aesthetic concerns”. Among those who adopted automatic drawing, which allowed them to suppress all conscious control in favour of chance, was Bridgwater. She experimented with automatic ink drawing as a means of accessing and expressing her subconscious, without bounds. Impressed, Breton wrote in the 1940s: “Bridgwater brought a new purity of outlook to British Surrealism, returning to the early days of the movement, to its ‘automatic’ beginnings in France”.

Bridgwater also wrote much poetry, populated by the same symbols from her drawings and the recesses of her mind: birds, plants, spirals and “twisted forms”. She successfully published her poems in significant surrealist and modernist publications.

In 1942, Bridgwater held her first solo show at Jack Bilbo’s Modern Gallery in London. By 1947, Breton selected her and Maddox as two of just four British Surrealists, to be exhibited at the International Surrealist show at Galerie Maeght in Paris. Although Birmingham’s male Surrealists’ shunned London’s artists, Bridgwater played a critical role in bridging the gap between the two competing cities. In part, this was because she made a close and significant friendship with fellow female Surrealist, Edith Rimmington. Here was yet another ally for Bridgwater, who found herself operating not only a regional surrealist, but as a minority female member of a movement, which primarily relied on women as sexualised muses, inspiring male desire, rather than operating as artists in their own right.

Like numerous other female members, from Leonora Carrington to Remedios Varo and Rimmington, Bridgwater appropriated the language of surrealism to express her own desires and fears. She subverted domestic spaces, reimagining them in claustrophobic terms, and played with imagery of life’s origins, focused on the symbolism of fertility.

But, and as has been the case for so many women artists throughout history, caring duties took precedence over Bridgwater’s career – she had to look after both her elderly mother and disabled sister throughout the 1950s and 60s. Bridgwater did then return to the scene in the 1970s, when she primarily produced collages, and exhibited in numerous group Surrealist shows. Then, throughout the 1980s and 90s, the art world’s interest in her work continued: she was included in retrospective Surrealist exhibitions in both public and private galleries in Birmingham, London, Milan and Paris.

Nevertheless, as both a regional and female surrealist, Bridgwater has been overlooked, especially during recent decades, and to many, she is yet an unknown member of this pioneering movement, in which she played such a leading role.

In 2022, and on the occasion of her first solo show in 32 years, it’s time that Bridgwater’s story was retold for today’s audiences. It comes amongst increased interest in the once-side-lined women surrealists, emerging from the shadow of their male counterparts. In 2019, Tate held a major Dora Maar retrospective, Frida Kahlo recently claimed the highest price paid at auction for a Latin American artwork, $34.9m, beating the record previously set by her husband, and Alice Rahon is being reassessed by San Francisco dealer, Wendi Norris, with an exhibition this year.

Deservedly joining the ranks of these ‘rediscovered’ surrealists, who should never have been forgotten, is Bridgwater. Highly regarded during her lifetime, by both critics and the founders of surrealism, she was a visionary force who changed the face of art history. Including never-before exhibited paintings, collages and drawings, (prices starting at £1,500) this exhibition presents her as an imaginative surrealist, whose complex narratives of the subconscious speak for themselves. A heroine of female, Birmingham and British surrealism, her surrealist state of mind still lives on, as it should.

This text is edited from my essay ‘Emmy Bridgwater: A Surrealist State of Mind’, which will be included in the catalogue for ‘Emmy Bridgwater: The Edge of Beyond’ on the occasion of the artist’s retrospective at The Mayor Gallery, London, which runs from 1 December 2022 – 27 January 2023

Thank you thank you for the Emmy Bridgewater extract. I’d heard the Leonora Carrington story before – but not her (video clip) non-cerebral analysis of art. Got at least one of Carrington’s Virago-published novels. And your Bridgewater text & illustrations are a delight. I got to this via the Farleys House & Gallery newsletter/ exhibition and then to the Mayor Gallery exhibition & video clip. Both referring to your larger text. Sussex to London to…Bham – where I live in Kings Heath. I’d discovered the few Emmy B works in that long ago Birmingham Museum & Art Gallery/ BMAG Surrealist exhibition – curated by the sadly deceased Tess… Thank you. again.