Six years ago, I moved from London to Birmingham. Since then, I have researched and written about the city’s art history, from the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and Arts and Crafts makers to the founders of Ikon Gallery. But, if there’s one movement which I love above all, it’s Surrealism and Birmingham was home to its most subversive and radical members. Recently, I spent the day recording a BBC documentary on the Second City’s Surrealists with comic legend Stewart Lee, as we toured leafy Edgbaston to bohemian Balsall Heath, in search of the true story of Birmingham’s Surrealists. Here, I share those sites of Surrealism, with behind-the-scenes photos of our day…

42 Lee Crescent, Edgbaston

A blue plaque at 42 Lee Crescent signals that this was once the home of Emmy Bridgwater. Born in Edgbaston in 1906, Bridgwater began her formal art education at the progressive Birmingham School of Art. Taught for three years by portrait artist Bernard Fleetwood-Walker, she became a skilled painter and draughtswoman.

But attending the 1936 International Surrealist Exhibition in London, she was inspired to join this radical new movement. Here, she met fellow Birmingham artists Conroy Maddox and John Melville, and the writer Robert Melville, working with them to establish the Birmingham Surrealist Group.

From this point onwards, Bridgwater invoked the Surrealist principle of juxtaposing unusual objects to reveal uncanny narratives; in her paintings and ink drawings viewers are invited into interior worlds, defined by a symbolic language of birds, eggs and organic forms.

Bridgwater’s desire to delve into the darker recesses of the psyche was characteristic of the wider Birmingham Surrealist Group, who were opposed to London’s surrealists who they perceived as “anti-surrealist”. Often overlooked and side-lined by art history’s narratives, these Surrealists of the ‘second city’ not only separated themselves from the London-based members but were determined to make art that was more revolutionary, more scandalous and ultimately more surreal, than that of their southern rivals.

Driven by this desire, the Birmingham Surrealists instead built strong and direct links with the Surrealists in Paris, including the movement’s founder; in return, they were welcomed and applauded, and particularly Bridgwater. As the movement’s founder André Breton wrote in the 1940s: “Bridgwater brought a new purity of outlook to British Surrealism, returning to the early days of the movement, to its ‘automatic’ beginnings in France”.

Bridgwater’s art proves that for her Surrealism was, above all, a state of mind. Alongside her fluid pictorial experiments, she also wrote much poetry, populated by the same symbols from her drawings and the recesses of her mind: birds, plants, spirals and “twisted forms”.

In 1947, Breton selected her and Maddox as two of just four British Surrealists, to be exhibited at the International Surrealist show at Galerie Maeght in Paris. Both were also chosen to sign the 1947 declaration of the Surrealist Group in England, proving that they had become two of the most important members of the movement.

29 Speedwell Road at Balsall Heath

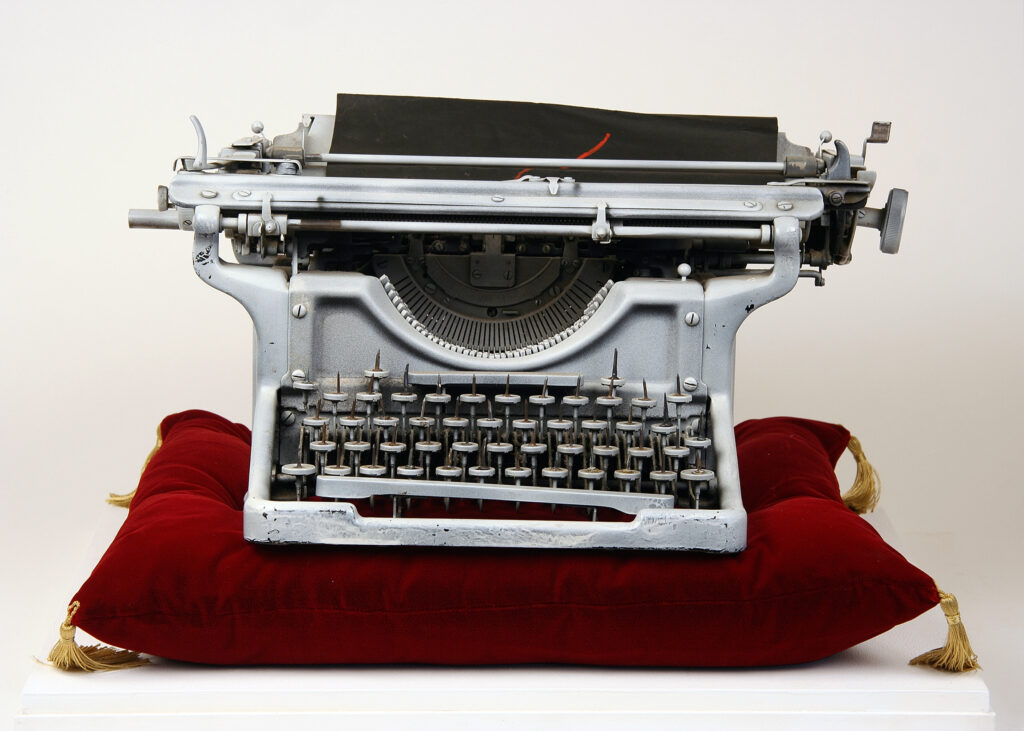

Conroy Maddox was to Birmingham what Salvador Dalí was to Paris, spending 70 years as a committed surrealist, creating paintings, collages and sculptures including his legendary typewriter, ‘Onanistic Typewriter I’, 1940, a useless typewriter with spikes on the keyboard, which evokes the Brummie humour.

Although the surrealists each had an individual style, they also acted as a collective, and were brought together by Maddox. An extrovert, who loved debate, he would welcome the surrealists into his 11-room house in Balshall Heath, for fortnightly gatherings. In an interview he once recalled these events:

“We had a friend who worked in the laboratory and he used to bring pure alcohol, so we would open the bottles and knock out about half a pint and fill it up with pure alcohol, which was quite potent, you know, you’d be talking to someone leaning against a wall and suddenly they would collapse in front of you.”

During the late 1940s, Maddox’s guests included the jazz star George Melly, dancers, academics and students from the University of Birmingham. In fact, it was through these gatherings that Desmond Morris became involved with the movement:

“True, I was attending lectures, taking notes, and making copious drawings from the microscope, but my preoccupations with the art world were still a major distraction. As soon as I had arrived in Birmingham I had set about exploring the local art scene and found, to my great pleasure, a thriving surrealist group centred on the home of the painter Conroy Maddox. Perhaps painter is the wrong word for him — he was a theorist, an activist, a pamphleteer, and a writer, as well as an artist — in fact, the total surrealist, typical of and traditional to that movement. He was as much concerned with surrealist ideas as with the production of art objects.”

University of Birmingham

The University also provided Morris with inspiration for one of his great surrealist objects:

“Behind the zoology department there was a rubbish dump and on it, one day, I spotted a discarded elephant’s skull. I was surprised that anyone would want to dispose of such an awesomely magnificent relic, but I was told that this one was in rather poor condition and no longer suitable as a scientific specimen.”

“I was surprised that anyone would want to dispose of such an awesomely magnificent relic, but I was told that this one was in rather poor condition and no longer suitable as a scientific specimen.

As far as I was concerned, its eroded surfaces rendered it even more remarkable, as a piece of natural ‘sculpture’ – what the Surrealists referred to as an objet trouvé. I decided that such an object should inspire a sense of wonder and determined to bring it to people’s attention.

It was extremely heavy and I had to enlist the aid of a number of hefty helpers, who assisted me in carrying it down the road to the nearest tram stop. The conductor refused to allow us to sit with it in the tram, insisting that it was ‘luggage’, and made us stow it under the stairs with a group of suitcases, where it was already beginning to take on a suitable irrelevancy”.

Arriving in the city centre, Morris left this surrealist object sitting in a shop doorway on Broad Street…

Broad Street

The next day, “A dinosaur in Broad Street” was the headline in the local Birmingham newspaper. “Below it”, Morris says, “was a photograph of two policemen struggling to force a strange object through the door of a police-car. It appeared to be a huge skull, so massive that it was clearly jamming in the open door. What it was doing in the centre of a busy industrial city was not clear. The paper played up the mystery angle and noted that a museum expert had been called in to identify it”.

Kardomah Café

And surrealism lives on in the city today. Inside Tyrwhitt, a men’s clothes shop on New Street, are remnants of the Kardomah Café where the surrealists once met to share ideas. On one wall is the original mosaic, featuring roses and leaves. I have no doubt that the Surrealists would love that it’s a clothes shop, filled with headless mannequins standing around today.

RBSA Gallery

Surrealism also lives on in the archives of the RBSA Gallery, which houses an original Emmy Bridgwater drawing featuring one of her bird-women who seem to be seeking freedom.

From the start the Birmingham surrealists saw themselves as opposed to the London lot, and were determined to prove that they were more radical, and more subversive. In fact, the industrial city of Birmingham, the city of a thousand trades, was the perfect playground for their movement. Moreover, while London Surrealism only lasted a short while (Surrealist activity in London virtually ceased in 1939), the Birmingham Surrealists remained committed throughout their careers.

The Trocadero

It feels fitting, then, that while Paris had its Café de flore, and Vienna its coffee shops, Birmingham’s Surrealists took to the streets, private house parties and the Trocadero pub, where we can still drink to them today!

Enjoyed the R4 programme on the Birmingham surrealists. Good follow-up to the 2022 exhibition at Tate Modern. Bought Desmond Morris’s ‘The British Surrealists’ there. Interesting biogs, including E Bridgwater, Conroy Maddox, Mellors, Melville. Programme helped bring it more to life. Have a neighbour who’s an Aston Villa fan and university statistician – surreal enough? Another friend supports AVFC while being from Gibraltar and an observant Sephardi Jew and craftsman in glass. Best wishes.

Hi Ruth, I listened to the programme in the week and found it very interesting. I ashamed to say that as someone who worked in the Local Studies section of the Reference Library for many years I never came across the group or was ever asked about them. I did some work back in the 70s on the reaction in Birmingham to the Spanish Civil War which included looking at several literary and intellectual figures who were active in the city in those late 30s years including,Auden, McNeice, John Cornford, Philip Toynbee, the Longfords and various University figures. I was wondering out of interest if you have come across any connections between the Surrealists and these writers or indeed did the group, such as it was in its early days, have any political affiliations or interest. Pretty much all the writers with the exception of Tolkien were supportive of the Spanish Republic. Congratulations on the research for the programme, Peter