Today, the term ‘muse’ carries negative connotations, particularly within feminist art history. However, the muse can be viewed from another perspective altogether – through that of the female gaze. Here are 10 contemporary women artists and their muses, who are shattering stereotypes and subverting expectations.

Throughout art history, male artists have made claim to their female muses. Since the 19th century, when the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood painted their sisters, wives and mistresses as mythological heroines, the muse has been positioned as a passive, female model at the mercy of a great male artist.

However, at their origin in ancient Greece, the muses were 9 goddesses of the arts and sciences. Clio, Euterpe, Thalia, Melpomene, Terpsichore, Erato, Polymnia, Ourania and Calliope were invoked by poets, musicians, makers and thinkers, before bestowing creative inspiration upon them.

Drawing on this divine imagery, contemporary women artists are now painting new life into outdated tropes. Rejecting romanticised images and representing a more diverse cast of sitters, they are reframing the muse as an empowered protagonist in the making of their immortalising portraits.

Depicted as Thalia, the Muse of Comedy, is actress and comedian Katherine Parkinson who can be seen laughing while boating in the frame of Roxana Halls, an artist best known for depicting wayward women who refuse to conform to societal norms on her cinematic canvases. Halls equates “painting with performance”, recognising her protagonists as co-conspirators in the creation of layered narratives.

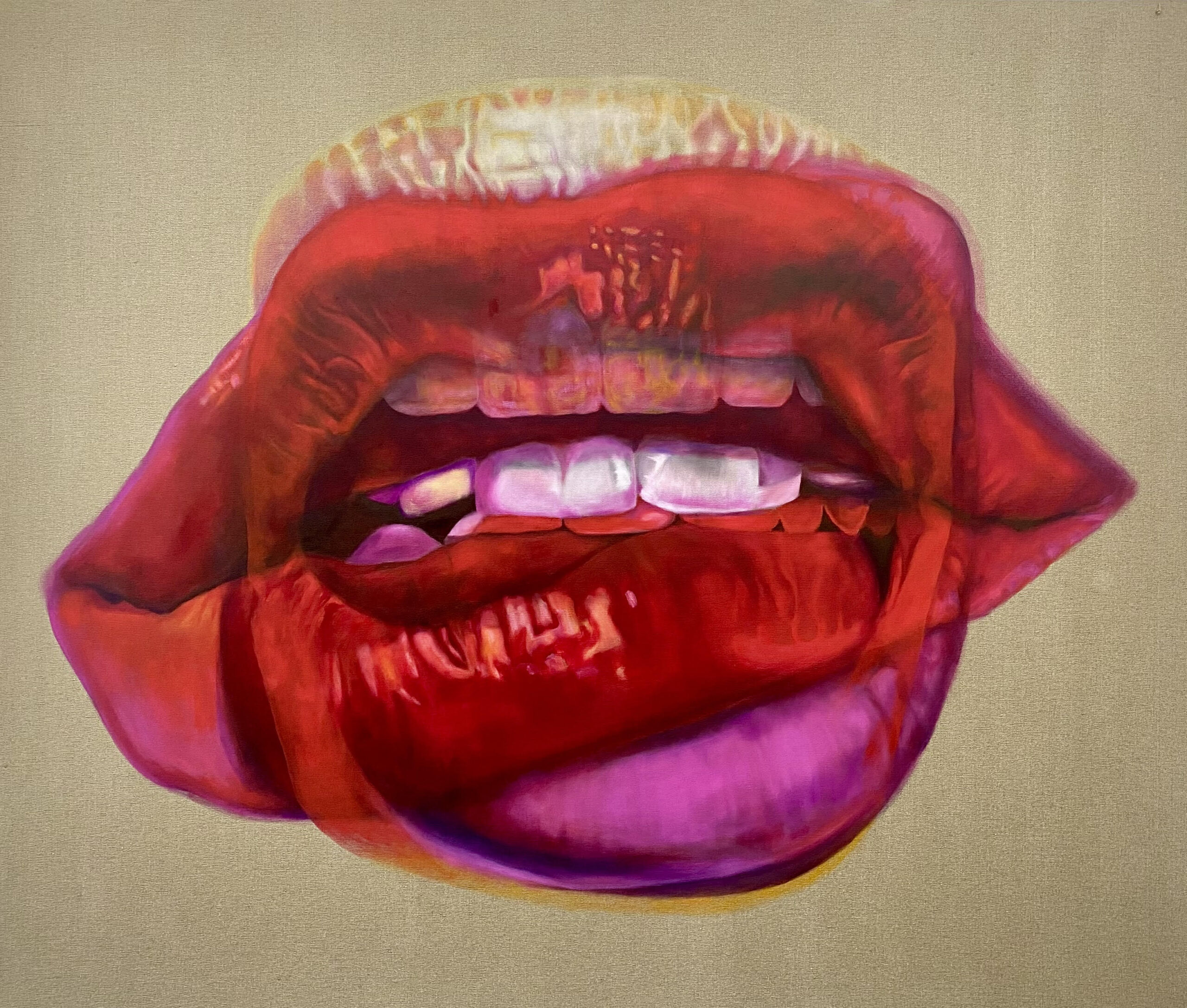

Like Halls, Annis Harrison also breaks conventions of women being seen smiling politely, lips pursed, in portraiture. She has framed Polymnia, the Muse of Sacred Hymns, as open-mouthed in her statement painting, ‘Words come out to play-ayyy’. As she has explained:

“The importance of storytelling through song and poetry has had through the ages and across all cultures. I then started thinking of Gospel music its role in informing and educating people who could not necessarily read. And also Hip Hop as a form of wordplay, now finally ‘recognised’, with literature awards such as the Pulitzer Prize.

I therefore chose to represent Polyminia as multiple mouths belonging to multiple black women on a bare canvas, layered on top of each other to represent many voices at the same time, and to celebrate that wonderful instrument that is our voice.”

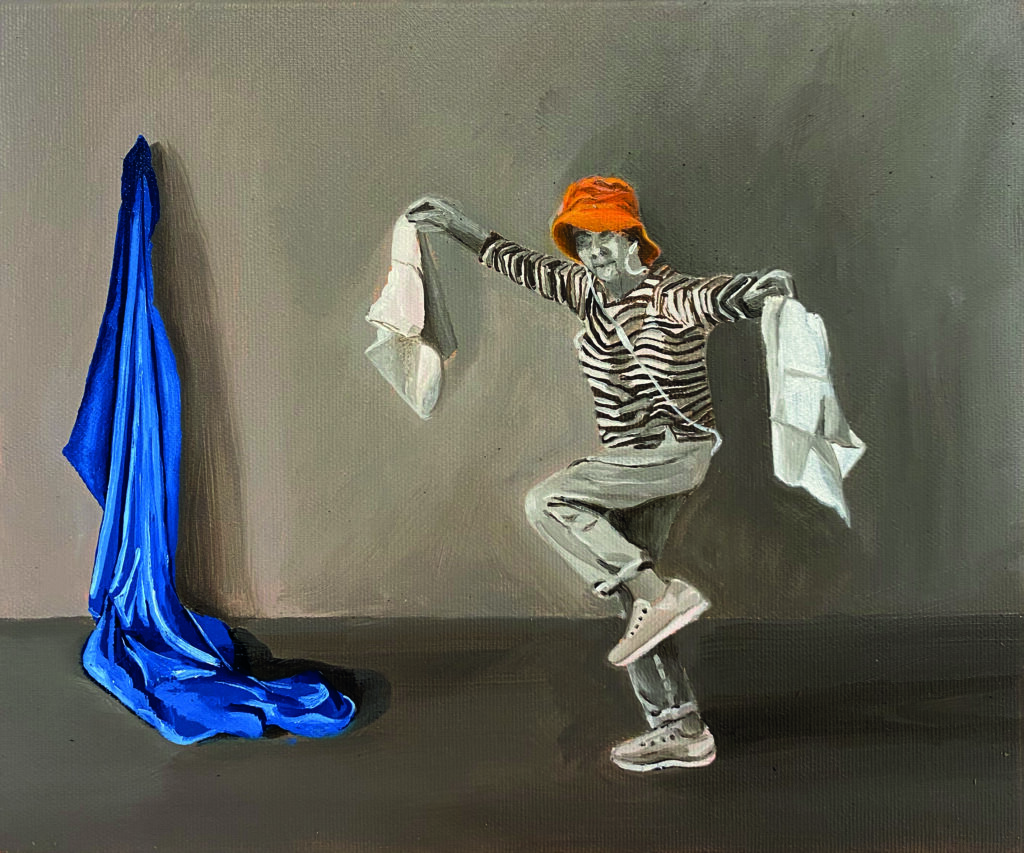

A musical score continues in Lindsay Simons’ painting ‘Emily Euterpe’, in which her muse plays a piccolo in the landscape, which references Sandro Botticelli’s springtime scenes. Such symbolism recurs in Carolyn Blake’s series, which feature a Greek vase and rich blue fabric hanging from the walls of a house, as if holding memories in its folds.

However, Blake’s muse is modern. Her partner Annette collaborated with her for these ambient paintings in which she appears as Terpsichore, dancing to music only she can hear through AirPods. It’s as if Annette is keeping her personal memories safe, and the artist deliberately separates her subject from viewers.

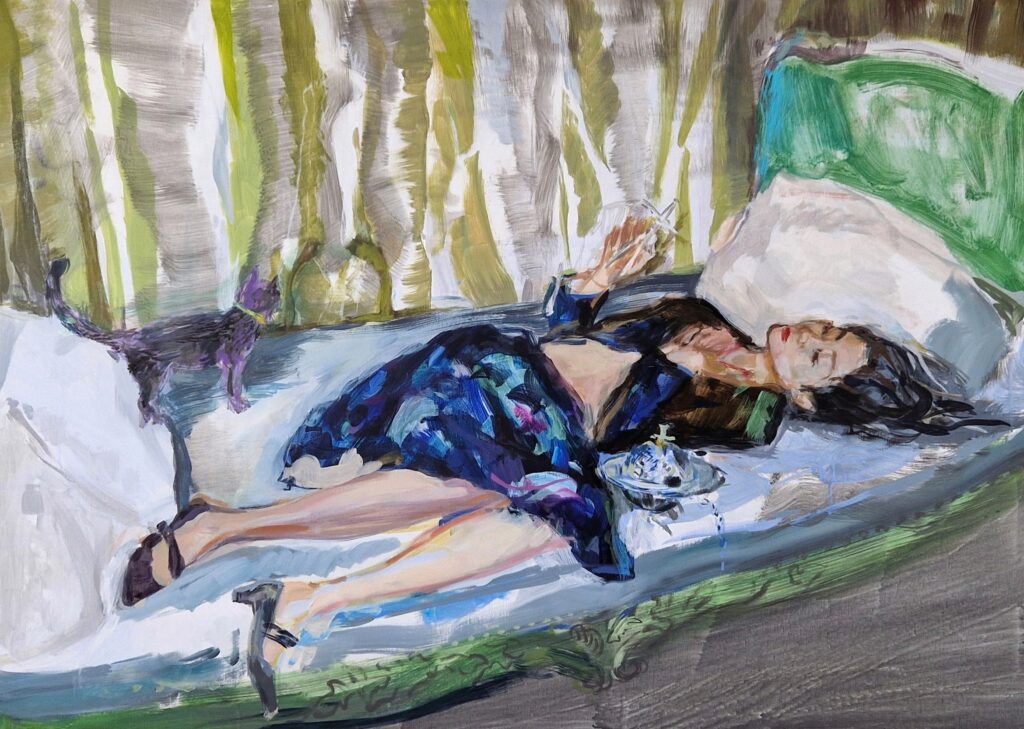

Pictured in her own private space, too, 90s Cantonese pop star, Faye Wong, has inspired Elaine Woo MacGregor. In her expressively painted composition ‘Urania’s Love – Shanghai Flâneuse’, the Muse of Astrology and Astronomy is a star herself, posed as if for a billboard campaign and clutching a shiny compass in one hand.

“I wanted my painting to have the look and feel of a Shanghai billboard with a filmic and quirky interjection of a cat and the gentle musing expression of Faye Wong. Classical Urania’s compass or staff, and the celestial globe is replaced by an imagined Vivienne Westwood metal handbag and a school drawing compass. She is not wearing a crown of stars; she is a star herself. It a strikingly casual pose, one that many of us can relate to but the theatricality of it all reminds us that it is a staged fashion-shoot”, says the painter.

Behind other closed doors, Francesca Currie has riffed on ‘The Rokeby Venus’ to portray her male actor-friend Lewis as Erato, looking lovingly upon himself in a mirror which in the history of art has typically been associated with female beauty and vanity.

In her personal painting, emotion has been brushed onto the textured aluminium panel. Lucy Andrews’ father emerges as the Muse of Tragedy, Melpomene, escaping temporarily from his alcoholism by tending to the garden. However, his flame thrower burns and scorches the earth, representing the impact of addiction on his family’s lives.

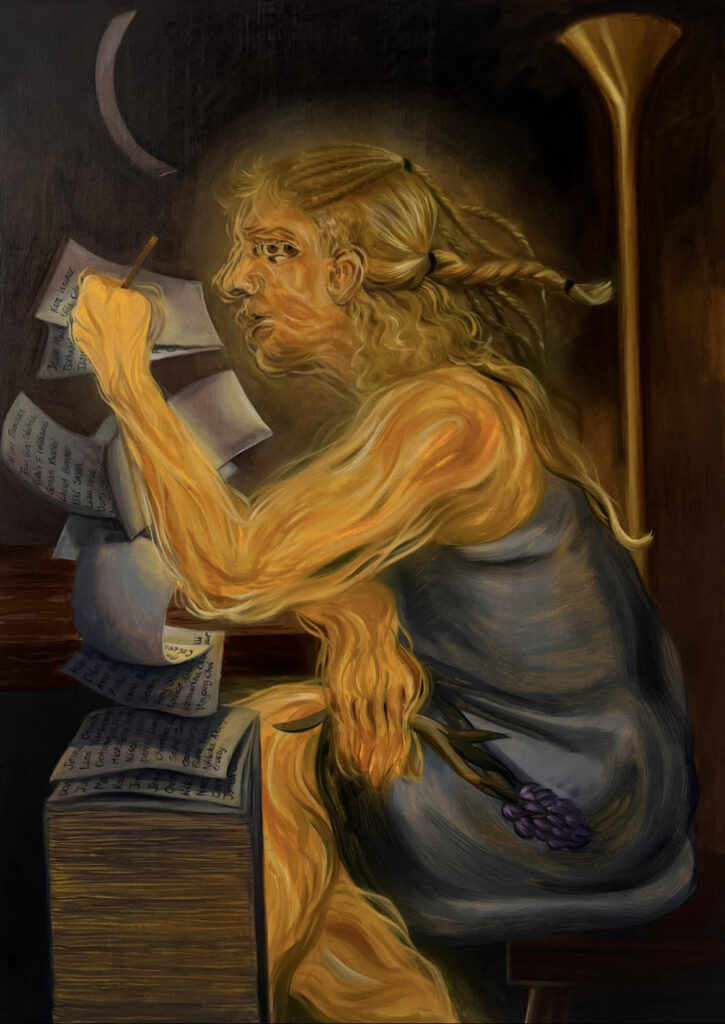

In contrast, Clio, the Muse of History, is more than human. Painted into multitudinous life by Louise Reynolds, she writes down the names of countless female artists in a flurry of papers which assemble into a huge book by her side – a task still not complete. As the artist explains:

“My painting emulates Clio as painted writing in the book of history by Artemisia Gentileschi, except in my depiction she is writing down the names of countless female artists in a flurry of papers which assemble into a huge book by her side. They are all names of artists I greatly admire in my practice, and all living. I hope it signifies that we are in a time now where female artists are being celebrated more than ever before, yet there is still so much to be written.

Clio’s face and form flicker with lots of different features, hopefully to suggest that the depiction of a goddess plainly as a beautiful white woman is outdated. Hopefully there’s a recognisable flicker for all women somewhere in her form. I’ve also included a couple of the symbols she was traditionally associated with – hyacinths and the heroic trumpet.”

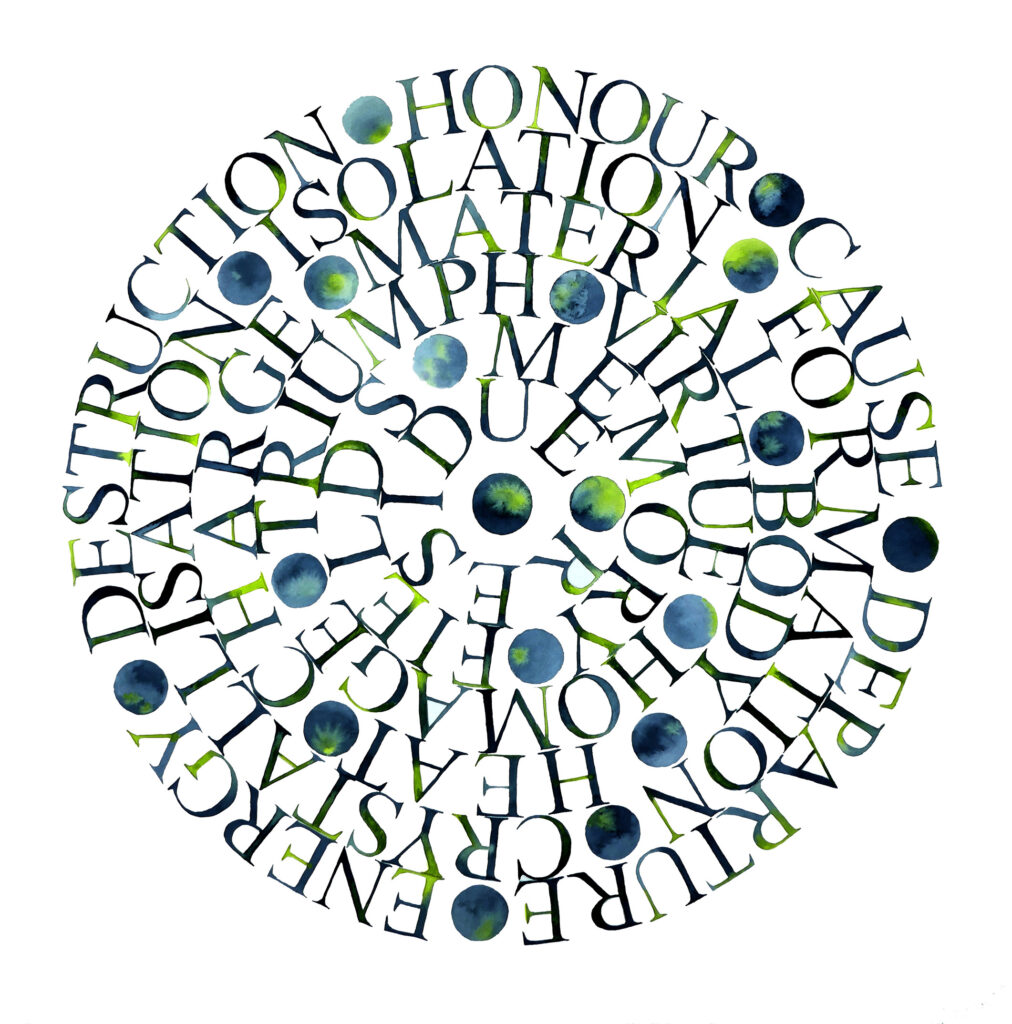

Liz Collini’s muse is a real woman from history, Marie Curie. Her watercolour and pencil work, ‘Radium Nouns (Marie Curie)’ was inspired by the scientist, and presents a selection of nouns from her Nobel Prize speech which the artist found when researching female scientists as modern era equivalents for the ancient sibyls (known to us though epic poetry).

Meanwhile, Ava Khera’s Muse of Epic Poetry and Eloquence, Calliope, inspires a modern female writer: within a verdant spring garden they stand side by side on a bridge of their shared imagination.

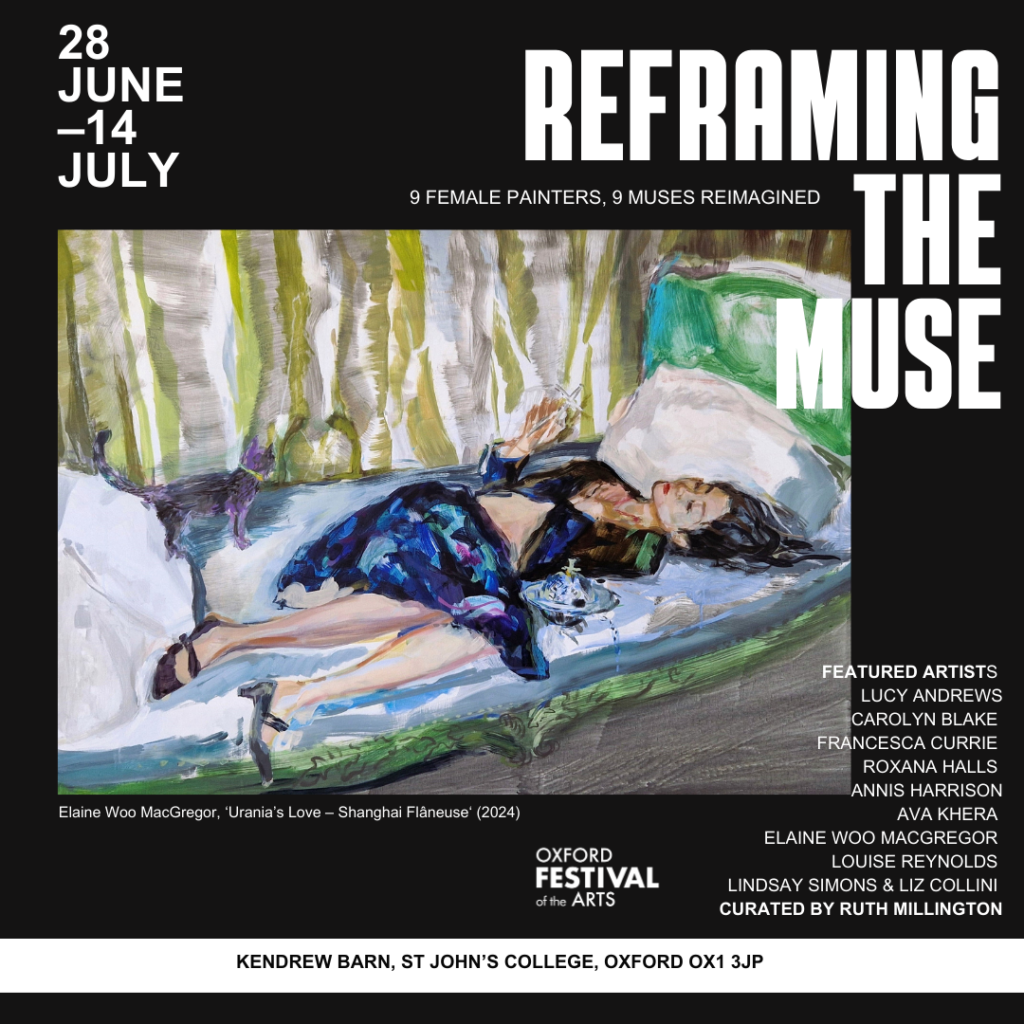

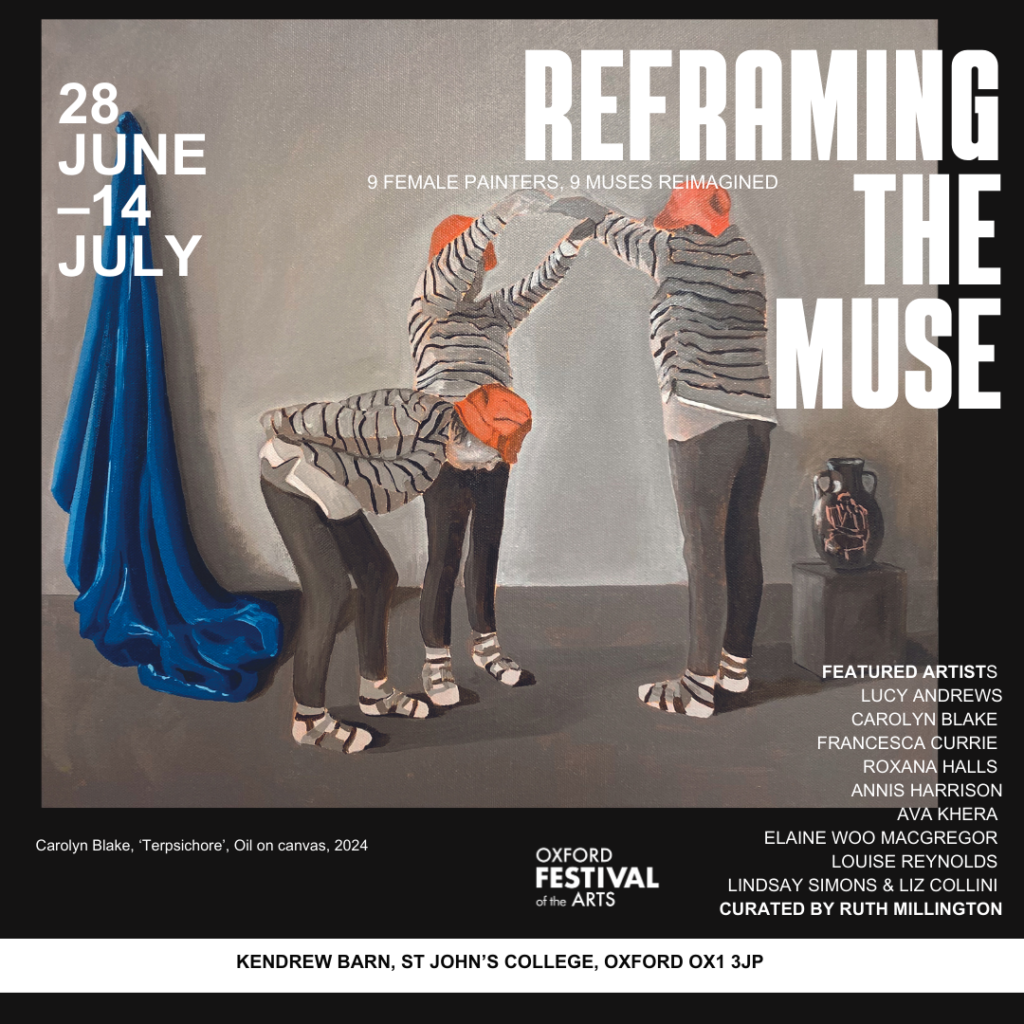

Reframing the Muse will take place from 28 June – July 14 at St Kendrew’s Barn, Oxford as part of Oxford Festival of the Arts. Curated by author and art historian Ruth Millington, this exhibition draws on research and writing from her book MUSE: Uncovering the hidden figures behind art history’s masterpieces (Square Peg, 2022).