Portrayals of the artist-muse relationship are all around us: in novels, famous films, binge-worthy TV series and, of course, art history’s narratives. But beyond fictional stories, such as ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’, what is an artist-muse relationship really like? Having researched this very topic for the past 5 years, resulting in my book MUSE, I discovered that fact is stranger than fiction when it comes to great artists and their inspiring muses, from the ancient world to today…

Meet the 9 muses of Greek mythology

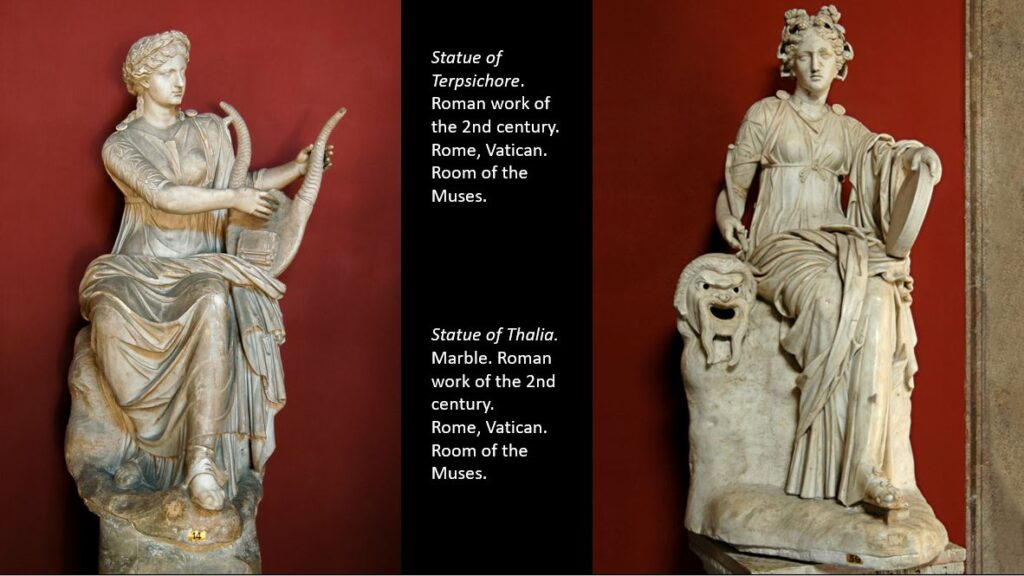

At their origins, in ancient Greek mythology, there were 9 muses. According to Hesiod’s Theogony (7th century BC), these divine sisters were daughters of Zeus, king of the gods, and Mnemosyne, Titan goddess of memory, and each could inspire certain art forms and held knowledge:

• Calliope (epic poetry)

• Clio (history)

• Euterpe (flutes and music)

• Thalia (comedy and pastoral poetry)

• Melpomene (tragedy)

• Terpsichore (dance)

• Erato (love poetry and lyric poetry)

• Polyhymnia (hymns and sacred poetry)

• Urania (astronomy)

In ancient art and architecture, we often seen them in with Apollo, who was the God and patron of poetry, holding instruments or with symbols of their creative power. In Homer’s epic poem, The Odyssey, the narrator asks the muse to ‘sing’ to him, allowing him to tell the story. The muses, at their origin, possessed real power! And it’s worth pointing out that the word ‘Museum’ comes from the Greek ‘Mouseion’, Shrine of the Muses, devoted to learning and the arts, which they represent.

But, this concept of the muse has evolved over time, and dramatically so.

During the Renaissance: their drapes and dresses fell away to reveal bare bodies, painted in soft, fleshy tones. They appear as seductive mistresses, feeding the fantasy of men, both in and outside of the picture frame. We find that muses have become icons of idealised and sexualised beauty.

Then, as early as the thirteenth century, the arts saw another major change in the relationship between the creator and the muse: visual artists and writers were increasingly influenced by real-life, rather than mythological, subjects. Dante Alighieri famously wrote about Beatrice Portinari as ‘the love of his life and inspiration muse’.

By the Victorian era, the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood were painting models who were friends, fellow artists, wives, sisters and lovers, including Fanny Eaton, Jane Morris and Elizabeth Siddal. Artists had become enamoured with, and creatively dependent upon, the muses they knew personally.

But what role have these muses really played in their relationships with artists?

Inside the artist-muse relationship

Elizabeth Siddall, Dante Rossetti and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Let’s start in the 19th century with one of art history’s most iconic muses, Elizabeth Siddall, who played a pivotal role within the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, inspiring many of its members and none more than Dante Rossetti.

In her 1896 poem In an Artist’s Studio, Christina reflected on the relationship between her brother and sister-in-law, while exposing the gap between the positions of man and woman, artist and model, in Victorian society: ‘One face looks out from all his canvasses… A saint, an angel; – every canvas means / The same one meaning, neither more nor less. He feeds upon her face by day and night, / And she with true kind eyes looks back on him…’

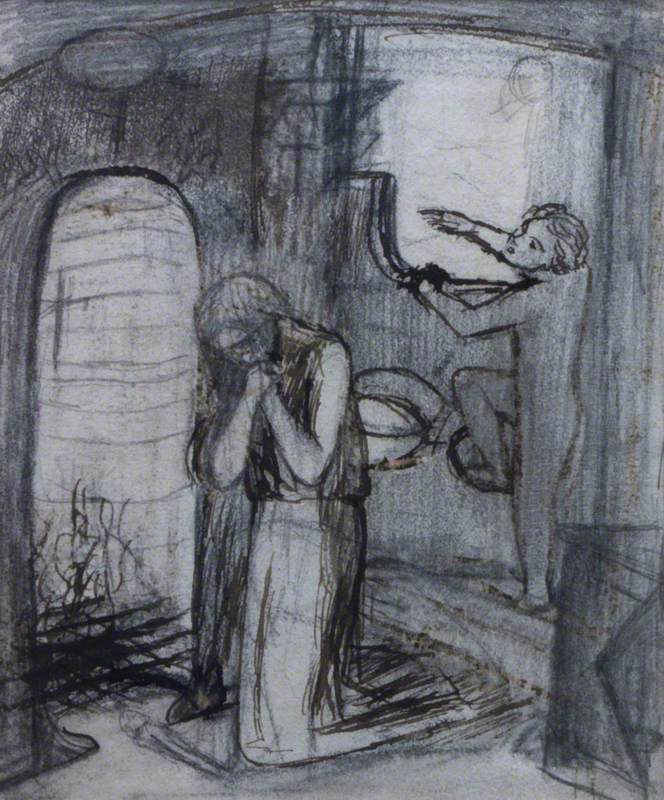

But Siddal was also a talented artist and poet, and inspiration flowed both ways for this pair. ‘The Siddal-Rossetti partnership was a mutual commitment to art, poetry and each other, despite the power imbalance that inevitably existed’, explains curator, art historian and writer, Hannah Squire.

‘They shared artistic commissions and created pieces of artworks together, harmonising their styles and ideas. When depicting the same figures their art is clearly inspired by each other’s compositions. For instance, Siddal’s drawing Sister Helen, 1860, is an artistic response to Rossetti’s poem of the same name.’

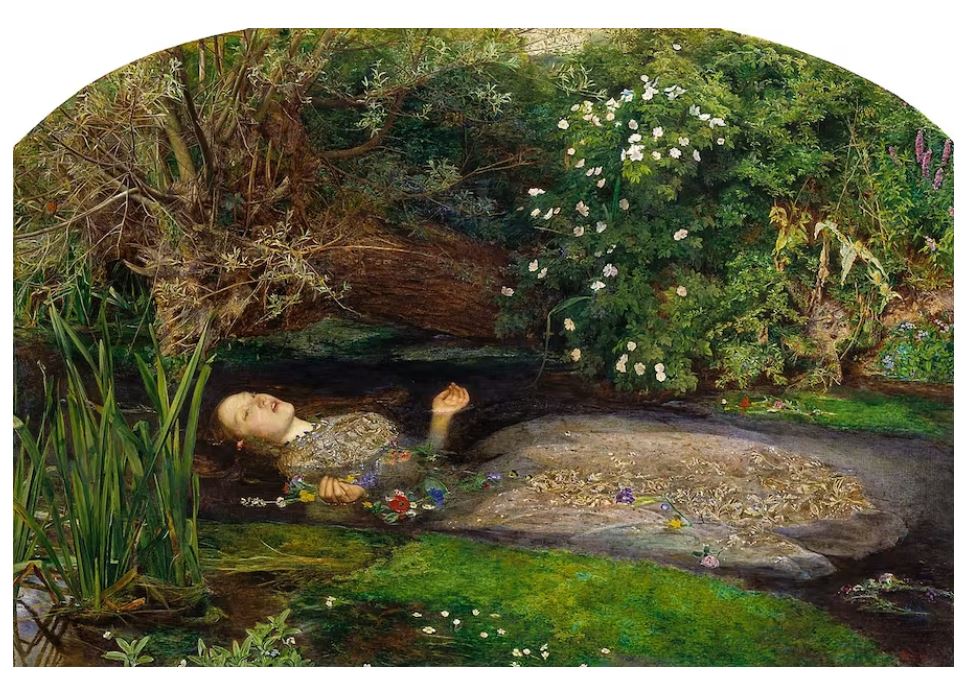

One of the most well-known works which Siddal modelled for is John Everett Millais’ Ophelia, which was completed in 1852. She posed in a bathtub filled with water, heated by oil lamps placed underneath the tub to keep the water warm (during winter time) for 6 hours, even when the lamps went out and the water became icy cold. Like many muses, Siddall was committed to the role, which can almost be seen as that of a performance artist.

Emilie Flöge and Gustave Klimt

Not all muses have been life models: Emilie Flöge (1874–1952), although pictured in several portraits by Gustav Klimt, brought her own talents as a fashion designer to what was a creative partnership between equals.

In 1904, Flöge opened the salon Schwestern Flöge with her two sisters, from where she designed and sold cutting-edge dresses, decorated in geometric shapes and swirling patterns. Her popular ‘Reform dress’ range was designed to liberate women’s bodies from the corset, allowing them to participate fully in everyday life.

It was in Flöge’s store that Klimt met many of his models, portraying them in the dresses designed by his muse; in effect, Flöge was responsible for fashioning Klimt’s trademark style on show in works such as Portrait of Hermine Gallia (1904).

When Klimt was on his deathbed his final words were reportedly, “Get Emilie.”

Dora Maar

Many of the greatest muses have also been artists, bringing huge amounts of creativity to the role. In her darkroom, successful Surrealist photographer Dora Maar (1907–1997) taught Pablo Picasso complex photographic processes, such as cliché-verre, meaning ‘glass picture’, which involves drawing handmade negatives on glass. Under her direction, Picasso used this technique to create a series of startling, unposed portraits of her.

Outside of the studio, Maar also indoctrinated the painter in her ultra-Left-wing politics, which infused not only Picasso’s portraits of her but also the epic anti-war mural, Guernica (1937).

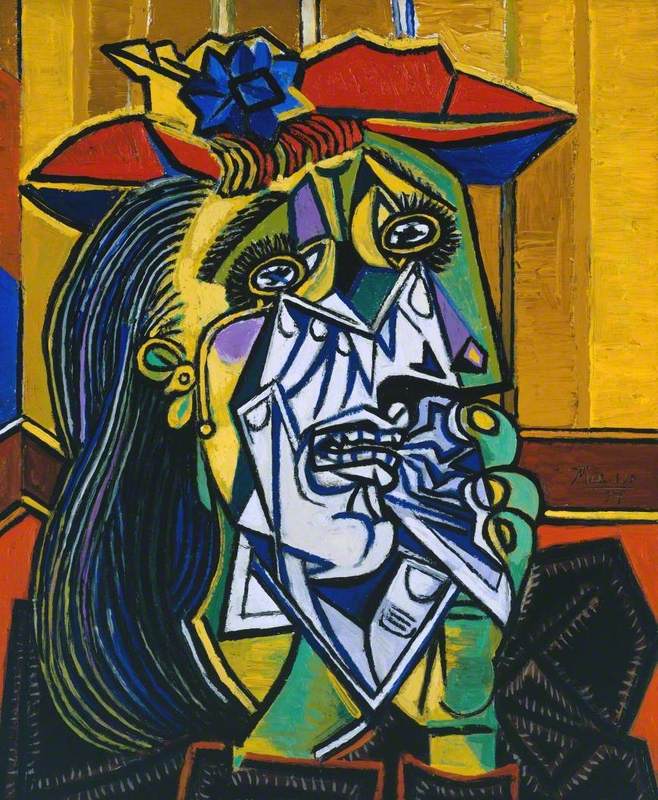

In fact, it was Maar who found Picasso a site large enough for this huge protest painting — the former headquarters of her radical political group, Contre Attaque. Inside the space, Maar photographed Picasso making the mural and helped him with sections of painting it. Leaving his bright palette behind, he created Guernica in black and white, influenced by Maar’s photography. There is even a darkroom spotlight in the picture, beneath which appears, for the first time, Picasso’s famous Weeping Woman.

That same year, Picasso painted a stand-alone portrait of Maar as The Weeping Woman, crying glass tears. This portrait is often read – in patriarchal narratives that frame women as romantic partners – as an inflection of her troubled relationship, and the abusive way in which Picasso treated her. But, if you look closely, you can see black warplanes in her eyes, proving Maar’s political convictions, which had a profound impact on Picasso.

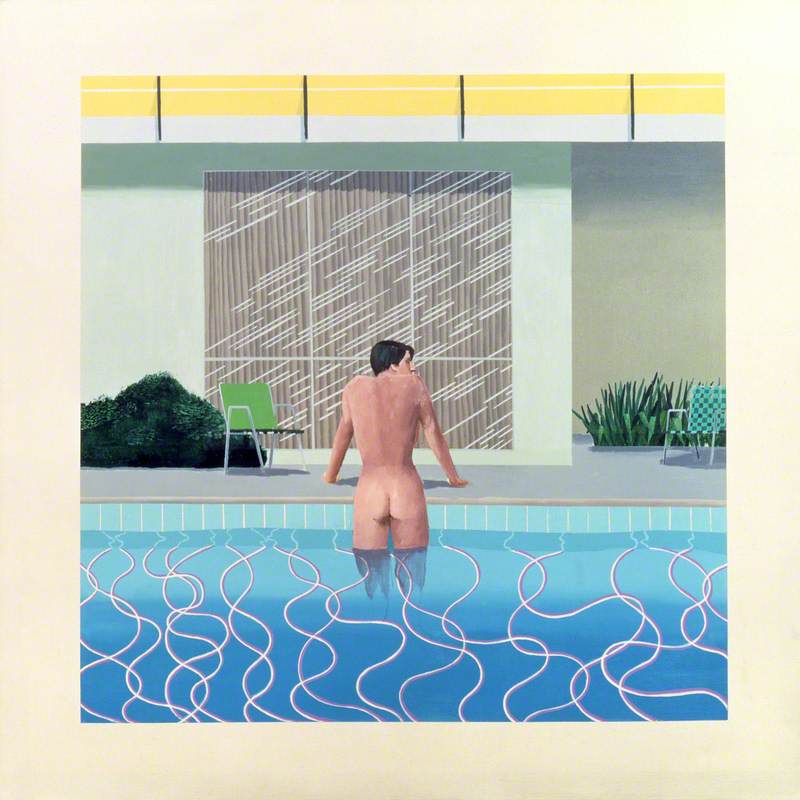

Peter Schlesinger and David Hockney

Men, too, can me muses.

David Hockney has collaborated with many naked male muses, although in his case adopting the male-on-male gaze to celebrate his sexuality on canvas. Among his most significant subjects is American photographer and artist, Peter Schlesinger.

It was LA-based Schlesinger who invited Hockney into his world of swimming pools in back gardens, including his own family’s. Hockney’s muse provided him with career-changing subject matter – he subsequently reworked the tradition of bathers in art through a homoerotic lens.

It was Peter Getting out of Nick’s Pool which won David Hockney the highly respected John Moores Painting Prize in 1967. This was the same year that homosexuality was partially decriminalised in the UK. Schlesinger acted as a bold icon for gay identity and culture in Hockney’s paintings before pursuing his own career as an artist.

And muses continue to inspire artists today.

New York-based, Chinese artist Pixy Liao takes provocative photographs of her younger Japanese boyfriend, Moro. Inside their home, he poses naked as a life-size sushi roll on the bed, allows her to cradle him in her arms and is pushed on a swing. In another playful double-portrait, the artist stares defiantly into the lens while pinching her male muse’s nipple. Moro adopts a submissive role, while still performing for the camera, an active participant in their romantic and creative relationship, caught in Liao’s camera.

While we often think of the muse possessed by, and serving, an artist, it’s clear that this is far from the truth. Instead, muses have often had great power over the artists they have inspired, bringing emotional support, intellectual energy, career-changing creativity and practical help to the role. If we look inside the artist-muse relationship, it’s clear that muses have played a pivotal role and undoubtedly left an indelible mark upon the makers who have immortalised them.

You can find my books on Booksradar.com – Books in the Right Order.

4 thoughts on “What is an artist-muse relationship really like?”