Situated on the Welsh Border is an ancient estate, called The Rodd, comprising a striking Jacobean manor house, 17th-century barns and orchard, set against a beautiful backdrop of vast, green countryside. This was the last home of the significant Australian artist, Sidney Nolan (1917 – 1992).

Luckily, it is open to the public, as his story, involving his most important muse, is one which has fascinated me for a long time…

Who was Sidney Nolan?

Once famous, but now largely overlooked, particularly in Britain, Sidney Nolan was one of Australia’s most important modern artists. Coming from humble, working-class origins – his father was a Melbourne tram-driver – as a young man, Nolan was shy but determined to break into Australia’s art scene.

In 1938, he sought out a couple, who had established their reputation as influential patrons of contemporary Australian art, Sunday and John Reed. Sunday came from a wealthy family, and John was a successful lawyer; they poured their collective wealth into buying art from Melbourne’s galleries, and they also began to back a small group of emerging artists, providing them with financial and moral support.

Nolan initially took his portfolio to John’s law office, hoping to impress him. That same night, John took Nolan’s art home to show Sunday, and the next evening they invited him to dinner at their house, Heide.

Heide was a large Victorian farmhouse, located on the outskirts of Melbourne, which came with six hectares of land. This was the spot where the Australian impressionists had come to paint, and it was ideal for what the Reeds had in mind; they wanted to create a retreat where artists could stay, paint and share in their vision of creating a radical new style of modern Australian art.

Sidney Nolan had just the talent that they were seeking, and they accepted him into their circle of artists at Heide.

What inspired Sidney Nolan to paint?

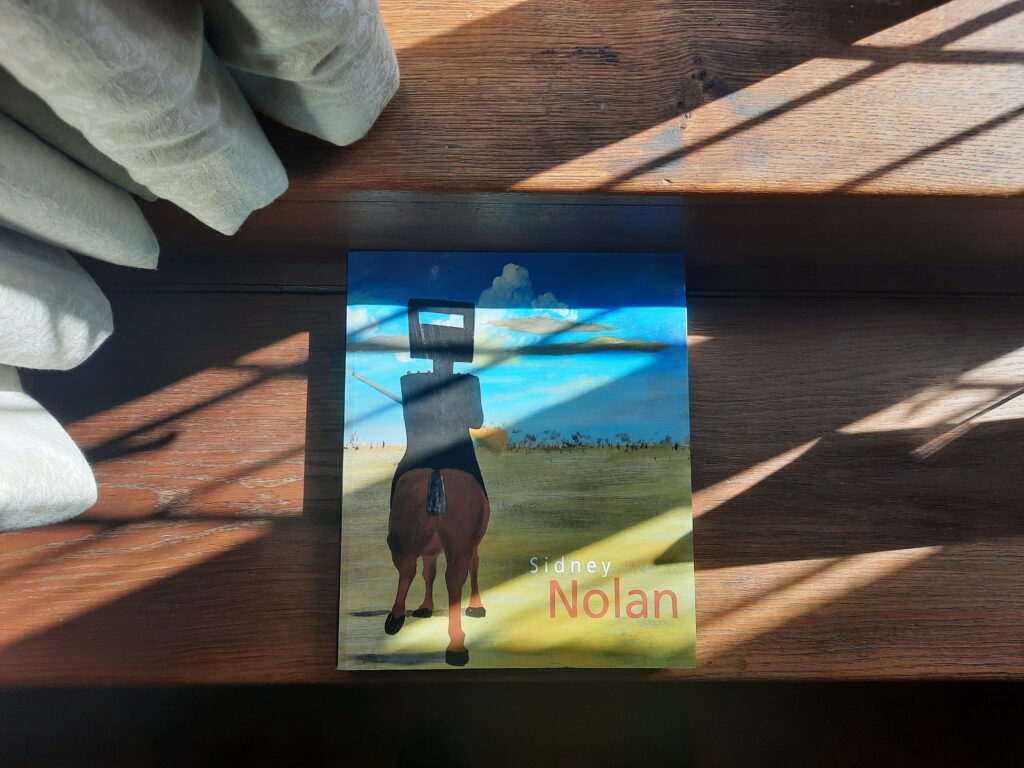

Nolan is most famous for his ground-breaking series of paintings of Ned Kelly, which he painted at Heide.

Kelly was a 19th-century Australian outlaw, bushranger and gang leader, who has become an infamous, and controversial, figure in the country’s history. While Kelly was a much-feared criminal in the eyes of many Australians, he was also a symbolic, anti-establishment hero who fought against the British colonists and corrupt police government. Nolan perceived of him, and portrayed him, in this light:

“Obviously, I have treated Ned Kelly as some sort of hero,” the artist later reflected.

Throughout Nolan’s paintings, Kelly appears against the stark, simplified backdrop of the bush, in his homemade armour, often on horseback. These images are a celebration of Australian history as indelibly tied to its landscape.

But there was another inspiring force in his life and work…

Nolan’s real-life muse, Sunday Reed

In 1945, Nolan painted Rosa Mutabilis. Beneath a wide, blue sky and inside a large, abstracted green garden stands a single bush of white roses, from which emerges a young woman. Intertwined with the flowers, she appears to belong to this idyllic realm. The figure in this picture is Sunday Reed, depicted within the walls and gardens of Heide. During this time, the pair also entered into a romantic relationship, of which Sunday’s husband approved. Rosa Mutabilis was painted as a celebration of Heide in its heyday, during which time Sunday was Nolan’s patron and romantic partner, his mentor, ally and muse.

But, following a fall out with Sunday, which I write about in my book Muse, Nolan left Heide for good, resulting in a fierce debate over who owned the paintings he had made there: artist or muse?

Spray painted muses

Sunday wasn’t his only muse, however.

Leaving Australia for good in the 1950s, Nolan came to London, where he befriended a circle of modern British artists. In the 1980s, Nolan spray painted an extraordinary collection of abstract portraits in the ancient barns of his estate, The Rodd, which he had moved to in 1983. They mostly depict individuals that had strong personal significance for Nolan, including his brother (killed in World War II), close friend Benjamin Britten, Francis Bacon and fellow Australian artist Brett Whiteley.

Nolan’s paintings, whether made in Australia or the UK, tell emotive stories, about people and the places they belong to.

In the artist’s studio

A highlight of visiting The Rodd is seeing Nolan’s studio, that has been left undisturbed since he last worked there. Trestle tables are bent under the weight of his spray cans in every imaginable colour, while benches are filled with boxes overflowing with tubes of paint, toy trucks, cutlery, books and brushes.

While visiting The Rodd, you can also see a gallery, which has a programme of temporary exhibitions, enter into the manor house and huge barns, where an artist-in-residence works, and enjoy the surrounding gardens.

In 1971, Nolan published a book of poems, with accompanying illustrations, titled Paradise Garden, in which he expressed his distress and “shame” at the ongoing argument with the Reeds over his paintings. Heide, once a Garden of Eden, later became a season in hell. But, Nolan’s creativity was fuelled by a life-long fascination with the elusive notion of paradise, which he sought in the Australian landscape and then travels abroad, including, and ending at The Rodd.

Visiting The Rodd, I could see how it became another Paradise Garden for Nolan, as he worked within echoey barns on his final extraordinary, expressive portraits.

How to get to the Sidney Nolan Trust

The Sidney Nolan Trust is on the B4355 Presteigne to Kington road. To plan your trip, I recommend visiting The Rodd’s website here.

I stayed about 10 miles away in an idyllic lodge (with a hot tub!), at Black Hall Lodges, which I highly recommend…