Currently on show at Birmingham’s Argentea Gallery is ‘Fertile Ground’. The exhibition features two young female artists from the Midlands – Nilupa Yasmin and Madeleine Muir – both of whom use photography as a process to explore issues of identity and body politics. Since the 1970s female artists have used photography to explore notions of self, femininity and womanhood, picturing themselves in the frame. I wanted to see if this exhibition would add anything new to that narrative.

In the upstairs gallery I was immediately drawn to a large-scale, woven photographic installation, ‘Grow me a waterlily’, by Nilupa Yasmin. Throughout her photographic practice, the artist explores notions of culture, identity and anthropology, drawing on her South Asian heritage through the act of weaving. The artist explained to me that she had created this beautiful wall hanging by interweaving 42 self-portrait photographs together. Each individual photograph presents her numerous and multi-faceted characteristics as a British Bengali Muslim woman. For example, woven into the fabric of the work (and the artist’s identity) is a photograph of Nilupa dressed in her mother’s traditional wedding dress, at exactly the same age as when her mother had been married.

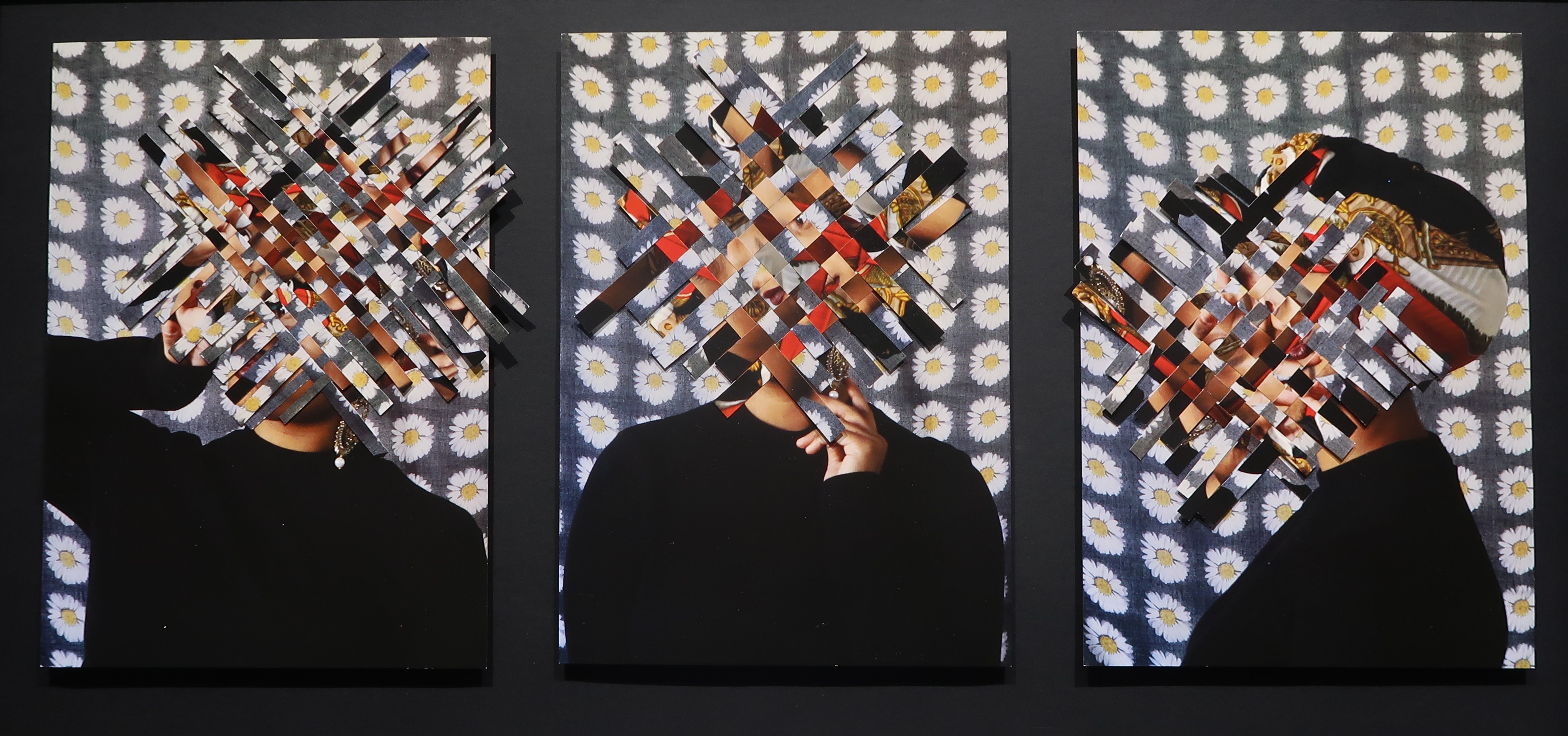

Opposite the large installation is a series of three self-portraits: established in traditional triptych, this work shows the artist cutting into her medium, carving up traditional imagery of the woman. Against, and into, the feminine floral backdrop, Nilupa has both disconnected and then interwoven fragments of her identity: the viewer is left to piece together clothing, costume and face, to establish the elements of idenitity, which forms at a complex intersection. The effect is visually striking, and echoes Francis Bacon’s iconic ‘Three Studies for a Self-Portrait’, in which the artist wanted to identify the essence of a person’s psyche, rather than simplifying and objectifying the human form.

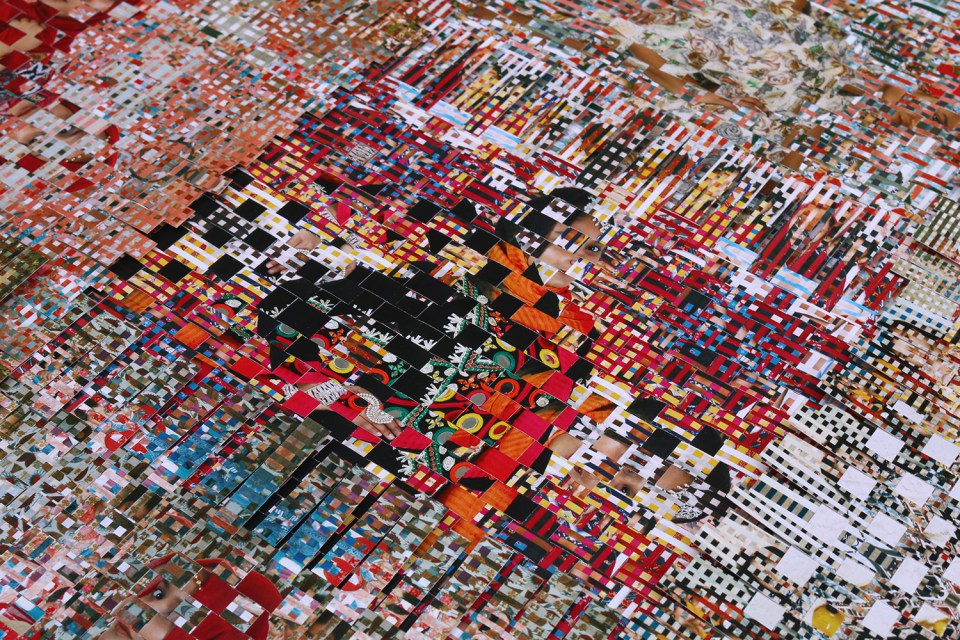

Her body of work also comprises a collection of small woven photographic patches and a large woven mat (exhibited as wall hangings). These beautiful pieces show the artist using the intricate craft of weaving as a study of the Foleshill area of Coventry. Defined by their rich combination of colours, patterns and textures, they reflect Foleshill’s former centre of the ribbon weaving industry together with its present day population of south Asian Muslim, Sikh and Hindu communities. These works also reference traditionally feminine materials: at first they appear purely decorative in the ornate combination of lace, golden thread and jewellery photographed and then embroidered together. And yet, Nilupa has used curated the collection of craft materials to make a powerful statement of identity, or multiple identities, as something essentially complex.

“It was only half-way through my first weaving project that my mother told me that my great-grandmother had been a weaver in Bangladesh” – Nilupa Yasmin.

In the gallery’s more atmospheric space downstairs, I was then confronted with a completely different set of images: Madeleine Muir has created a series of black and white self-portraits that examine teenage identity. An installation of 54 sequential photographs show the artist exploring the amount of physical space she, as a person, takes up. Individual self-portraits then show her personal response to this: some show her folding in on herself, hinting at an anxiety about her place in the world.

Here, self-portraiture becomes less an expression of self but a means of exploring and accessing things the camera can often not see: emotions, traumas, desires. This collection owes a certain debt to artist and photographer Jo Spence (1934 – 1992), who has been an integral figure within photographic discourse from the 1970s onwards. It was in 1984 that Jo Spence developed Photo-Therapy, adopting techniques from co-counselling. The considerable achievement of Photo-Therapy was to invert the traditional relationship between the photographer and the subject. If historically the subject had little control over their own representation, Photo-Therapy shifts this dynamic. The subject was able to act out personal narratives and claim agency for their own biography.

Certainly here, each collection of images explores the artist’s innermost feelings of confinement, apprehension and vulnerability. As an analysis of self-consciousness, with moments of sudden, explosive self-expression, they give a glimpse into a private, inner world behind the masquerade we perform when we go about our daily lives. In the age of Instagram, which has created another platform where many women still perform, present and adhere to the expected image of traditional femininity, this body of work seems somehow needed and necessary.

This exhibition shows that we do still need a new wave of artists to challenge the traditional, idealised imagery and views of the female form. In fact, many of the things women were fighting for in the 1970s—equal pay, the right to be safe, and access to free sexual health care—are sadly still far from resolved. There are additional enemies today, which are more insidious: across social media, we are faced with too narrow an image of femininity, often uploaded by women themselves. These two talented young artists re-tell what it means to be a woman now, exploring the female body, identity and the spaces in which women live, without filters. This important exhibition showcases the next generation of image-makers, who I hope to see more of.

Fertile Ground runs from 18th January – 10th February 2018 at Argentea Gallery in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter.