Reproduced by permission of the artists

As an artform, drawing has consistently been underestimated, undervalued and dismissed as a preparatory activity in an artist’s wider practice. However, hosting a British Museum touring exhibition ‘Drawing attention: emerging artists in dialogue’, Wolverhampton Art Gallery is challenging such preconceptions.

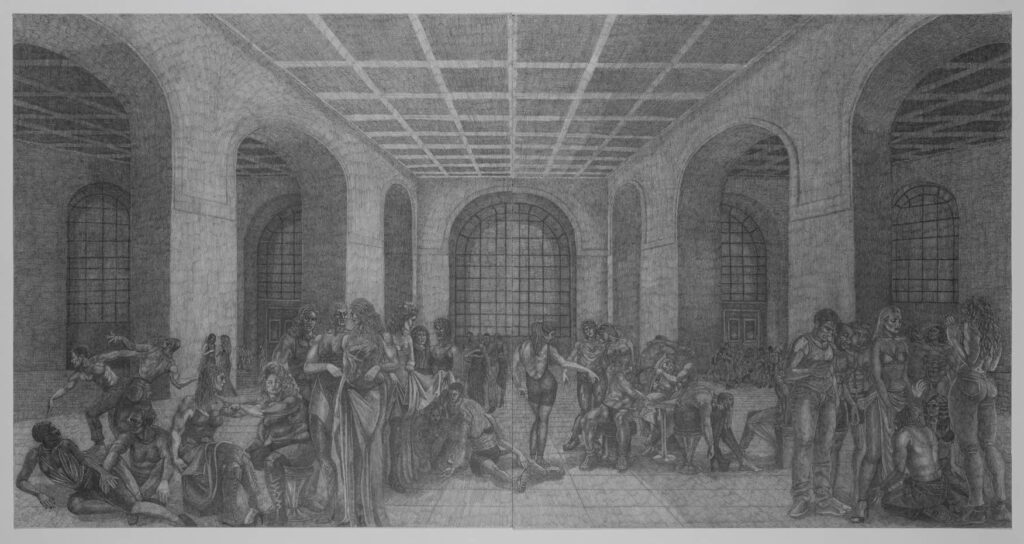

For a start, the show’s first work complicates notions that drawing must always be done alone. A monumental sketch, ‘Funny Girls’, 2019, by art duo Hannah Quinlan and Rosie Hastings demands that viewers look closely at what they are drawing, and saying, with their shared pencils.

On first glance, the meticulous drawing looks like an Italian Renaissance example. Deliberately toying with viewers’ expectations, the artists have depicted a tableau of figures defined by the same dramatic use of light and shadow, and sharp perspective, as that employed by the likes of Michelangelo.

However, Michelangelo has had a modern makeover: the idealised classical architecture has been reimagined as a gay club, inspired by a Blackpool drag cabaret theatre after which the drawing takes its witty title.

on the Sistine ceiling’. Engraving on paper, early 1570s.

Positioned next to this work is Giorgio Ghisi’s 1570s engraving ‘The Eritrean Sibyl, after Michelangelo’s fresco on the Sistine ceiling’. The exhibition is made up of pairings, some more successful than others, between masterpieces from the British Museum and the work of emerging artists.

In this instance, there is a direct relevance to the coupling, as Quinlan and Hastings borrowed a pose from the Sistine Chapel for one of their figures, assimilating Renaissance iconography to restore a sense of magnitude to LGBTQ+ spaces.

This sense of borrowing from, and subverting, traditional drawing practices runs throughout the exhibition, beginning in the first of three themed rooms, ‘Alternative Histories’.

This opening display also challenges notions of drawing as a gentle activity, pointing instead to its political nature, a statement made most strongly where Wolverhampton Art Gallery have included objects from their own Black Art Collection in the curation to invite new ways of seeing.

A highlight is Barbara Walker’s ‘I Can Paint a Picture with a Pin’, 2006, in which a West Midlands Police stop and search form has been printed over with a depiction of the artist’s son, who had been unjustly searched on a number of occasions.

Another imposing addition is ‘Regal’, 2000, in which Chris Ofili has accentuated his sitter’s afro to celebrate the beauty of Black identity. His drawing has been paired with Chila Kumari Burman’s ‘For Freedom We Will Lay Down Our Lives’, 1984, which presents a rebellious dancing figure to challenge more reductive representations of South Asian women.

Hopkins Foundation support © 2024 The Trustees of the British Museum. Reproduced by

permission of the artist

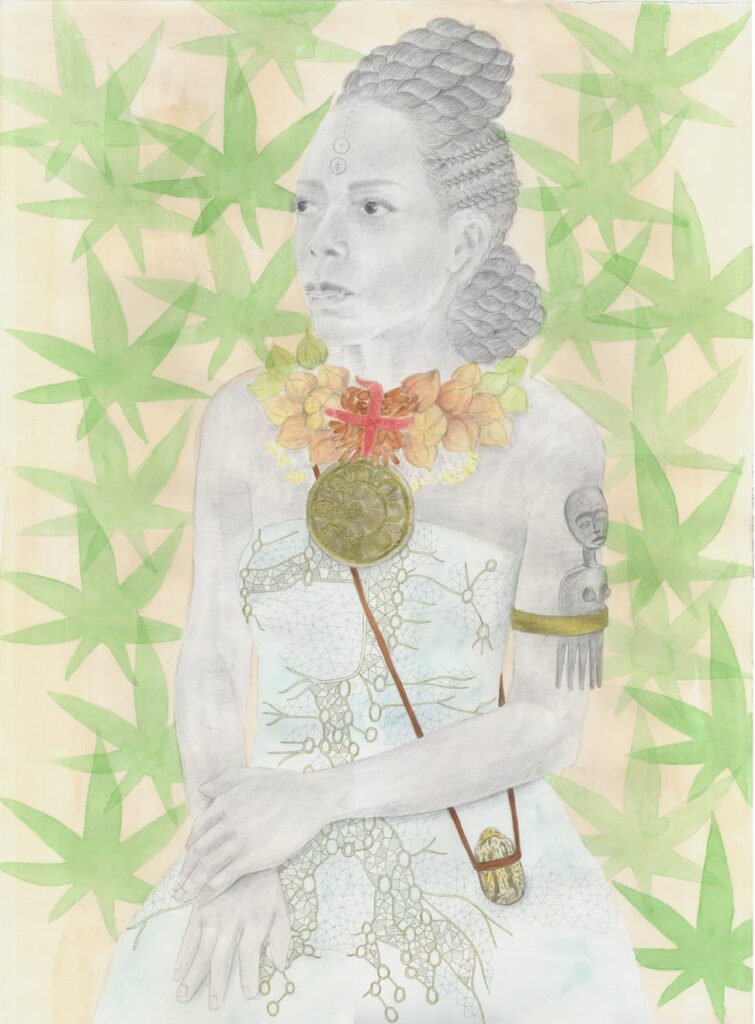

It is not just who an artist draws, but how, that matters. These figurative works create a conversation with a symbolic and thought-provoking drawing by Charmaine Watkiss’, titled ‘Double Consciousness: Be Aware of One’s Intentions’, 2021.

Taking up space on the paper, a Black female figure carries plants seed like a weapon, as if warning viewers about the poisonous qualities of the medicinal oil if misused. Positioned against a background of castor leaves, this muse is not just an object of beauty, despite the pretty patterns, but embodies traditions of herbal medicine in Caribbean culture.

Although beginning with her own likeness, Watkiss doesn’t draw direct self-portraits. In contrast, the show’s second room ‘Self and Other’ focuses on those artists who use drawing as a means for intimate self-reflection.

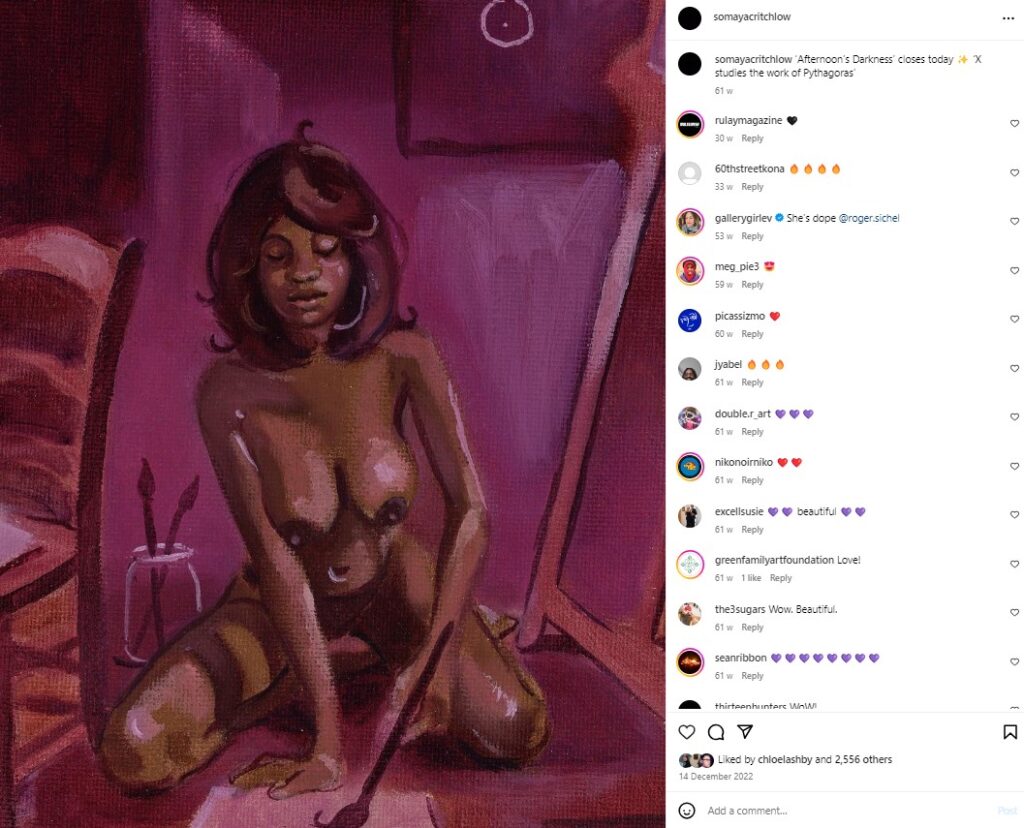

Challenging traditional notions of the gaze is Somaya Critchlow. Much like the better-known Claudette Johnson, who is also included in this curation, she renders self-possessed Black women who have presence and agency. While taking sexualised tropes as her starting point, the artist undresses taboos with her confrontational nudes.

In a direct challenge to art history, her compositions have been paired with an etching of Edouard Manet’s ‘Olympia’, 1865, in which a Black servant has historically been overlooked. Taking such precedents as a starting point, Critchlow is among those contemporary artists who invite viewers to look again at masterpieces of the past.

Acquired with Art Fund support © 2024 The Trustees of the British Museum. Reproduced by permission of the artist

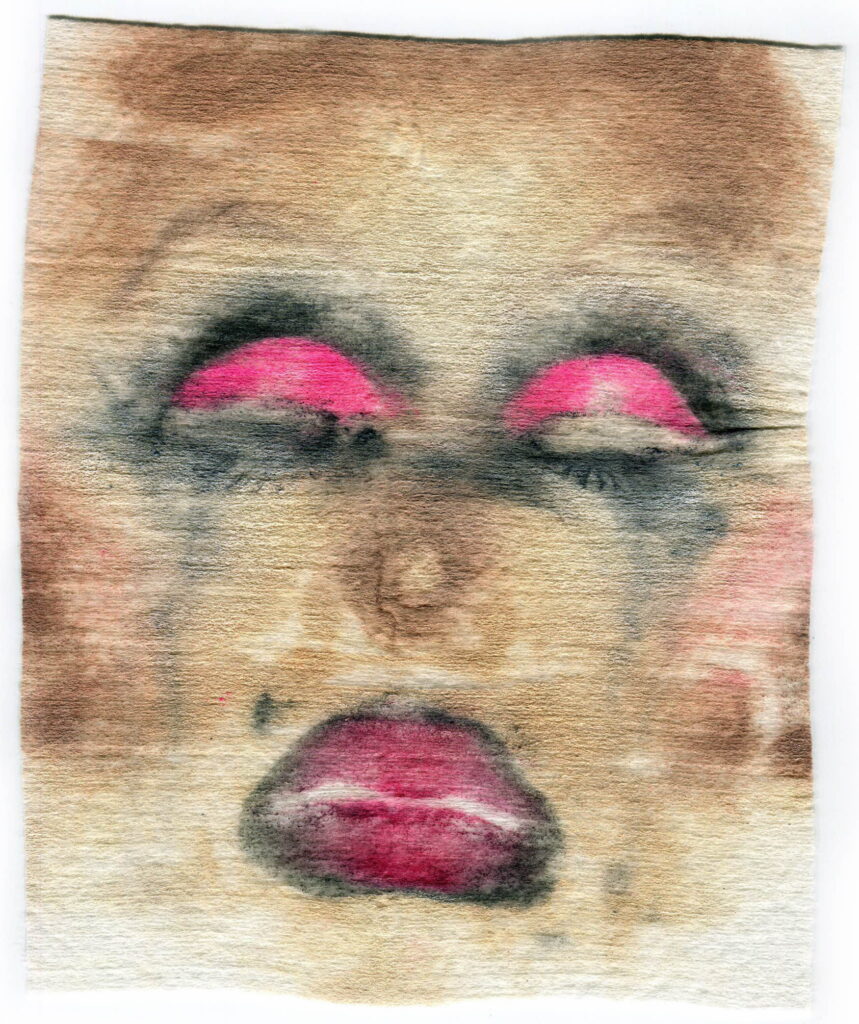

The show’s final room, ‘Medium and Materiality’, presents an artist’s chosen medium as their message. Sin Wai Kin’s ‘what you have gained along the way’, 2017, is a monoprint taken directly from the artist’s drag makeup at the time of London Pride 2017, as a means of protesting the event’s glitzy commercialisation.

Although this composition seems redefine what a drawing is, in using their body to create a direct impression on an everyday item, Sin echoes prehistoric cave artists who left handprints on walls.

After all, drawing has always been the most primal of art forms, through which artists have expressed themselves, protested, and shared stories which are too uncomfortable or complex to tell through words.

Pairing historical artworks with emerging talent, this compelling exhibition challenges stereotypes of representation and drawing in equal measure. Showcasing a diversity of contemporary approaches, often inspired by works of the past, it proves that drawing remains a daring and versatile means of expression at the very heart of an evolving art story.

To discover more contemporary drawing artists, you can read about the RBSA Gallery’s inaugural Drawing Prize here