Over the past few years, there’s been a trend for fictional retellings of myths and fairy tales. Female authors have been giving a voice to women characters, from Clytemnestra to Circe. But these modern titles are not the first to have shared legendary heroines’ stories from a feminist perspective, as proved by Wolverhampton Art Gallery’s major new exhibition: ‘Painted Dreams: The Art of Evelyn De Morgan’.

Once upon a time, or at least in the Victorian era, the pioneering painter Evelyn De Morgan twisted these tales to centre the likes of Morgan Le Fay, the Little Mermaid, and Helen of Troy in her frame. But her cast of mythical characters also reflect realities, carrying De Morgan’s more modern messages, from the personal to the political.

The prophetess Cassandra, cursed to see the future but never be believed, is a ravishing vision, dressed in long, flowing gown in a vividly painted composition from 1898. But the artist asks viewers to look beyond her subject’s beauty. Behind her stands the Trojan horse, referencing Cassandra’s prediction – that Troy would fall.

As the city is infiltrated, she tears at her golden hair in a moment of despair; De Morgan invites a sympathetic view of this woman who has been ignored, yet again. Could she also have been using this ancient character to allude to the Women’s Suffrage Movement which was gaining momentum that year? In 1889, De Morgan signed the Declaration in Favour of Women’s Suffrage, publicly presenting herself as a feminist and advocate for gender equality.

This feminist thread weaves throughout the entire exhibition. Another highlight is ‘The Love Potion’, 1903, which depicts the fearful enchantress, Morgan Le Fay. While a black cat curls up at her feet, stereotypes of the wicked witch have been replaced with a more compassionate depiction of the protagonist. Seated beside a row of old, leather-bound books, she appears as a woman of intelligence and learning, who uses magic for the greater good. As she pours her concoction, a window opens onto a scene of two lovers embracing. The scene seems to reflect proactive changes women were seeking at the turn of the century.

Rich with allegory and symbolism, De Morgan’s canvases reflect the inspiration she took from the earlier Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. However, while she shared their penchant for literary subject matter, there is a marked difference in her approach, particularly in her portrayal of female sitters.

In ‘The Hourglass’, 1904-05, a woman with greying hair is surrounded by luxurious, glowing tapestries and medieval furniture. But her expression is one of brooding sorrow, as she clutches an hourglass, in which the sand is swiftly running out.

The model for this poignant portrait was Jane Morris, a famous Pre-Raphaelite muse known for her long, brown locks and beautiful lips, which Dante Gabriel Rossetti painted through a lustful gaze. In contrast, De Morgan has portrayed Morris at the end of her life, replacing romanticised views of an immortal maiden with those of an ageing woman, coming to terms with her own humanity.

Next to it hangs a pastel portrait of Morris from around the same time. An exceptional drawing, it highlights De Morgan’s great ability to capture the human form. As one of the first women to study at the Slade, she was banned from drawing the male nude but allowed to work from female models.

Fighting for her rights, in 1883 she joined 25 prominent female students of the Royal Academy to demand access to life drawing and thus be able to pursue a professional artistic career. A reproduction of this important document is among the archive material relating to De Morgan’s life and work, adding contextual depth to the exhibition which forefronts her feminism.

Nature, too, is presented as a feminine force in paintings such as ‘The Cadence of Autumn’, 1905, in which five choreographed women represent the seasons of life. While three figures harvest an abundance of ripe fruit, painted in rich and autumnal tones, she has painted two women to the edge of the scene in a more muted palette as falling leaves swirl around them and death approaches.

Yet, death is not presented as an image of doom but as a phase of transformation, mirroring De Morgan’s own spiritualism – she believed in the afterlife and the ability to contact this spirit world.

Invoking a lunar magic, the moon also appears as a constant and protective source of light in most paintings, endowing De Morgan’s heroines with an ethereal quality. They seem to belong to the same enchanted realm, conjured up by their wondrous storyteller: De Morgan.

An illuminating addition, the final room presents the artist’s painstaking process, as local artist Paul Francis-Walker has recreated 3 of her lost paintings. Deliberately leaving his version of ‘The Spear of Ithuriel, c.1900, unfinished, it reveals her use of translucent layers to create colourful depth, which she adopted from Renaissance painters like Botticelli. Painted with jewel-like colours, her women shimmer in coats of cobalt blue, vermillion red, violet and yellow ochre.

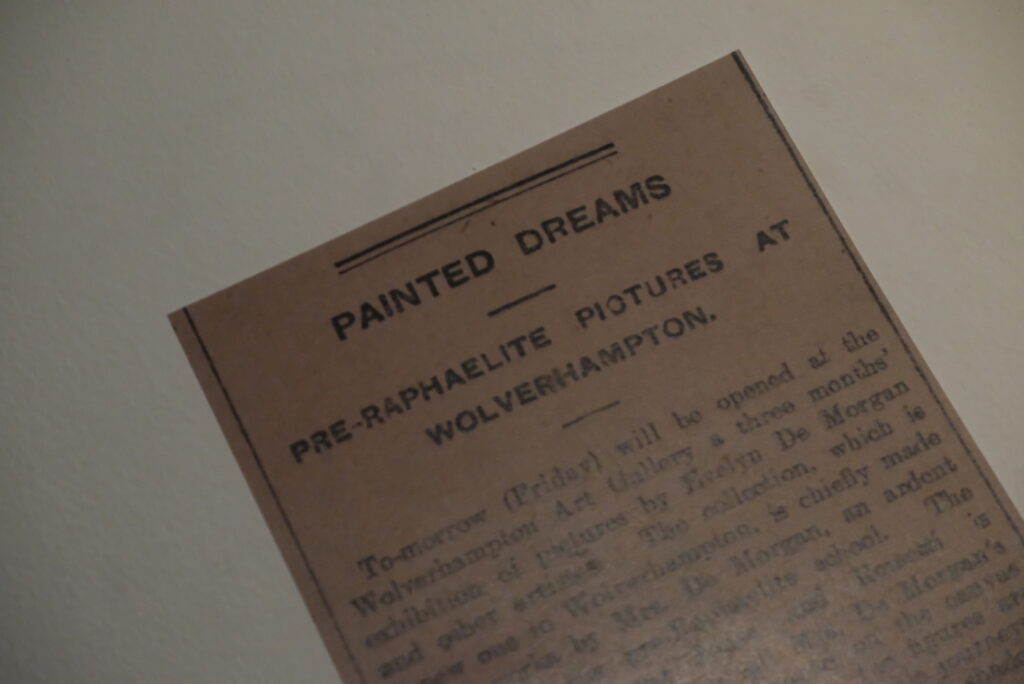

Wolverhampton’s show is a significant restaging of De Morgan’s ground-breaking exhibition at this same gallery in 1907. Back then, it earned a glowing review in the Express and Star, which referred to her works as ‘Painted Dreams’. Taking its title from this very writeup, 2024’s exhibition is just as deserving of praise today. At a time when feminist retellings are trending, this show celebrates a trailblazing artist whose captivating cast of women lead the way.

Painted Dreams: The Art of Evelyn De Morgan – Wolverhampton Arts & Culture is free to visit until 9 March, 2025.