As writer-in-residence at the Birmingham & Midland Institute, my desk overlooks the red-bricked School of Art on Margaret Street. Typically, before I start to type, I will stare out of the window, its ledge lined by overgrown spider plants, at this historic building. During these moments, I’ve often mused on other women writers and artists who have made their names in Birmingham, and none more than Mary ‘May’ Morris, although her contributions have since been obscured by a more famous father.

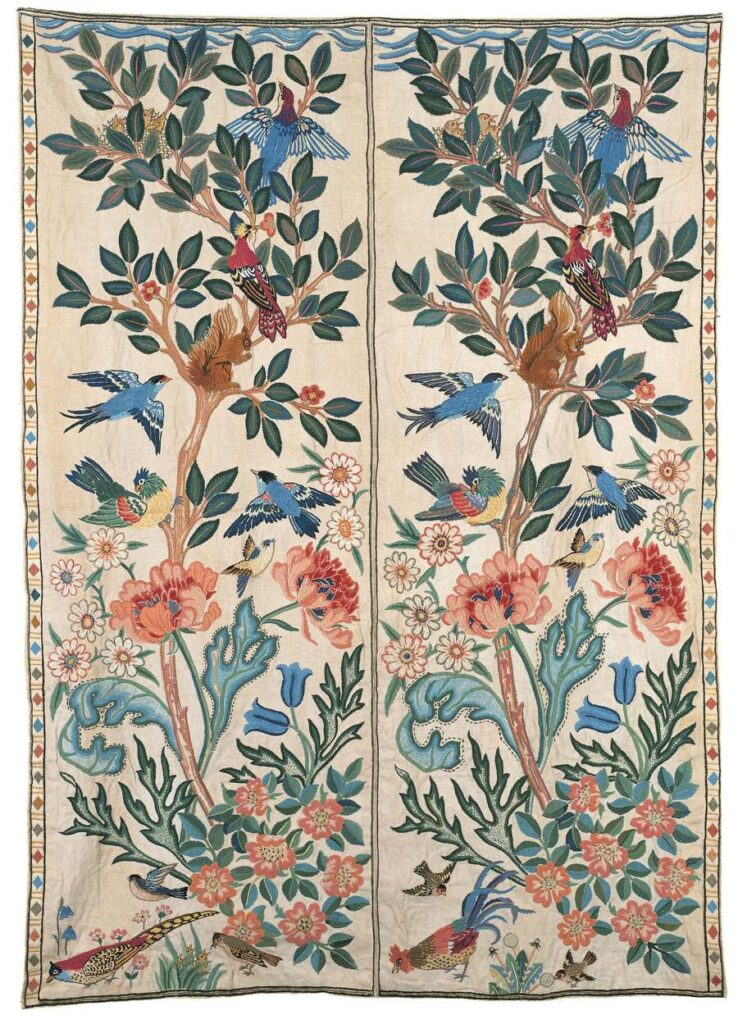

“Embroidery is the first thing I learned…I sat beside my mother at her embroidery frame and watched the needle come down and begged to be allowed to fasten the thread”, wrote the youngest daughter of William Morris in 1910. Largely home educated, she was taught needlework by her accomplished aunt, Elizabeth Burden, and talented mother, Jane Morris, who was also a significant muse for the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

An exceptionally skilled craftswoman, May joined the Royal College of Art to study embroidery at the age of 16. The school was located close to the V&A Museum, where she drew inspiration from the collection of hand-made embroideries from the Middle Ages, Opus Anglicanum. She believed that medieval embroidery was far superior to mass-produced modern textiles, and her appreciation, and belief in, traditional techniques became a key feature of the Arts and Crafts movement, which railed against the Industrial Revolution.

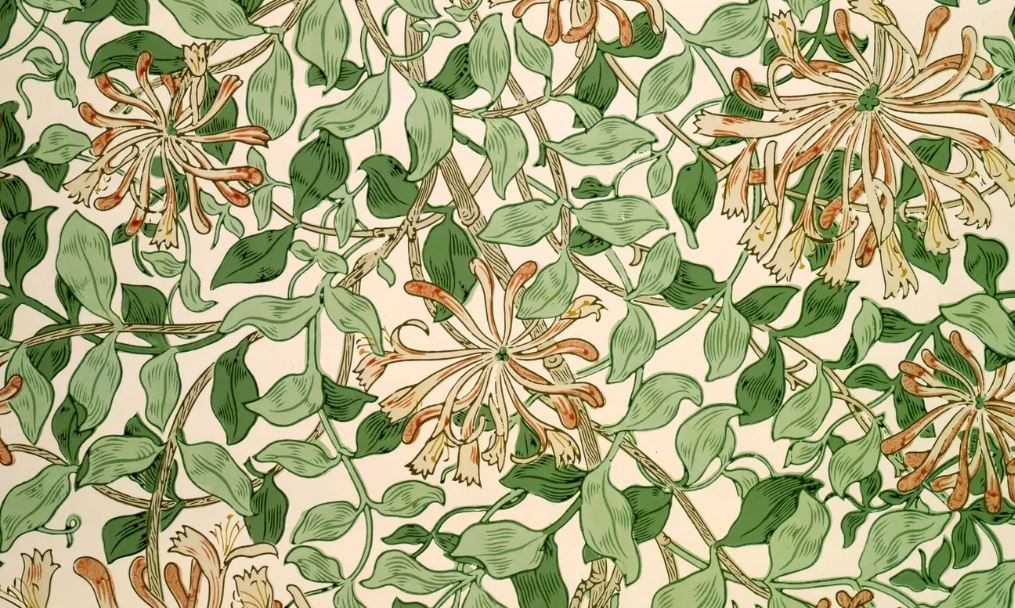

In the early 1880s, May began working alongside her mother and father at Morris & Co, and soon became the firm’s main designer, working on bed and cushion covers, pillow cases and tablecloths, and her renowned wallpapers. Several of her most popular wallpaper designs, including ‘Honeysuckle’ (1883) and ‘Horn Poppy’ (1885), were assumed to have been designed by William; however, the more delicate compositions, celebrating British flora and fauna, and grounded in the medieval tradition, are characteristic of May’s signature style.

May left Morris & Co. after her father’s death in 1896. By this time, she was established as an artist in her own right and set up an embroidery workshop. She began to teach design and embroidery at various schools, including Birmingham’s School of Art, which held a special status within the Arts and Crafts Movement. Here, crafts were considered equal to fine art. Moreover, in a scene dominated by men, the school welcomed and celebrated women artists on equal terms.

May played a significant role in teaching and supporting women artists in Birmingham. At Birmingham School of Art, she shared her creative ideologies, focused on handmade and historical techniques, with artists including Georgie Gaskin, Celia Levetus, Kate Bunce, Florence Camm and Mary Newill. Together, these women led the revival of embroidery, handmade crafts, jewellery and design. Across their practice are recurring motifs of the natural world, imagined in decorative patterns, and executed meticulously by hand. They invoked a return to simpler times, whilst raising the status of crafts from amateur pastime to serious artistic pursuit.

With the growth of the women’s suffrage movement at this time, May championed the rights of women artists. “It is the want of thorough training that hampers women in the arts, great and small,” she explained in an address to the International Congress of Women in 1899. In 1907, she founded the Women’s Guild of Arts, as no existing guild would then admit women:

“As I understand it, we are a body of women joined together as such, men always having their own organisation, to do what we are doing i.e. to keep to the highest level the arts by which and for which we live, to keep fresh and vital the enthusiasm, the belief – all the things which are the impetus of human endeavour”, May declared in an address to the Guild in 1907. Her aim, which she achieved, was to raise the status and rights of women artists and designers, in Birmingham – and beyond.

In turn, May also drew inspiration from the artists she worked alongside. With access to Birmingham School of Art’s workshops, she began to design jewellery around the turn of the 20th century, and her use of brightly coloured gemstones, rather than diamonds, shows the influence of the Birmingham jewellers Arthur and Georgie Gaskin, who were friends of the Morris family.

By the end of the 19th century, May had become prominent in the public eye. Her expertise on embroidery and jewellery gained recognition and she authored numerous articles and a book, Decorative Needlework, as well as lecturing in the UK and US. Through such work, she continued to elevate the status of crafts, such as embroidery, to an art form worthy of being exhibited and discussed in academic circles.

But May’s assertion, that craft skills should be valued as highly as that of fine arts, fell out of fashion, particularly with the arrival of modern art in the 20th century. Embroidery, needlework and other textiles have since been categorised, by the Western art world, as something that women simply filled their afternoons with, and marginalised by many narratives, which separate ‘high’ art from lowly domestic crafts.

In a letter from 1936, May wrote, in recognition of herself, “I’m a remarkable woman, always was, though none of you seemed to think so”. She was right, and her words feel more relevant than ever. Isn’t it time that women’s innovations in craft were given more attention and their rightful place within the canon of art history? Isn’t it also time that May emerged from her father’s shadow to receive the same acclaim as him? After all, it was many of her delicate, yet defiant designs, which ensured the success of Morris & Co.

So much more than just a designer’s daughter, May Morris should be more famous than she is for her work as an embroiderer, designer, jeweller, feminist and activist. Positioning herself as leading figure in the Arts and Crafts Movement, she influenced a generation of artists at Birmingham School of Art, while continuing to inspire contemporary creatives’ work, including my own.

Writing from the Birmingham & Midland Institute, with a view of Birmingham School of Art, May’s inspiring story is one which I have felt compelled to share. Just as she once spoke up, acting as a fierce advocate for the rights of women artists, so too does Mary ‘May’ Morris deserve to be appreciated, and credited, for her immense contributions today.

Further reading

May Morris: Arts & Crafts Designer (Thames and Hudson, 2022) by Jan Marsh et al

Decorative Needlework (Illustrated Edition, Dodo Press, 2010) by May Morris

Thank you for describing the work and achievements of May Morris. I have to admit that I knew very little about her before, even though I also taught at BCU and was inspired by her designs in some of my own work, mistakenly thinking it was her father’s. What a talent she was.