Digital protest art for Iran, focused on the symbolism of hair cutting, is a powerful new weapon in the fight for women’s freedom. While activist art has a long feminist history, these images are also breaking new boundaries…

For weeks now, protests have taken place across Iran, following the death of Mahsa Amini. The 22-year-old Kurdish woman was detained by the ‘morality police’ for failing to properly wear the hijab, and she died under suspicious circumstances, after falling into a coma, while in custody in Tehran.

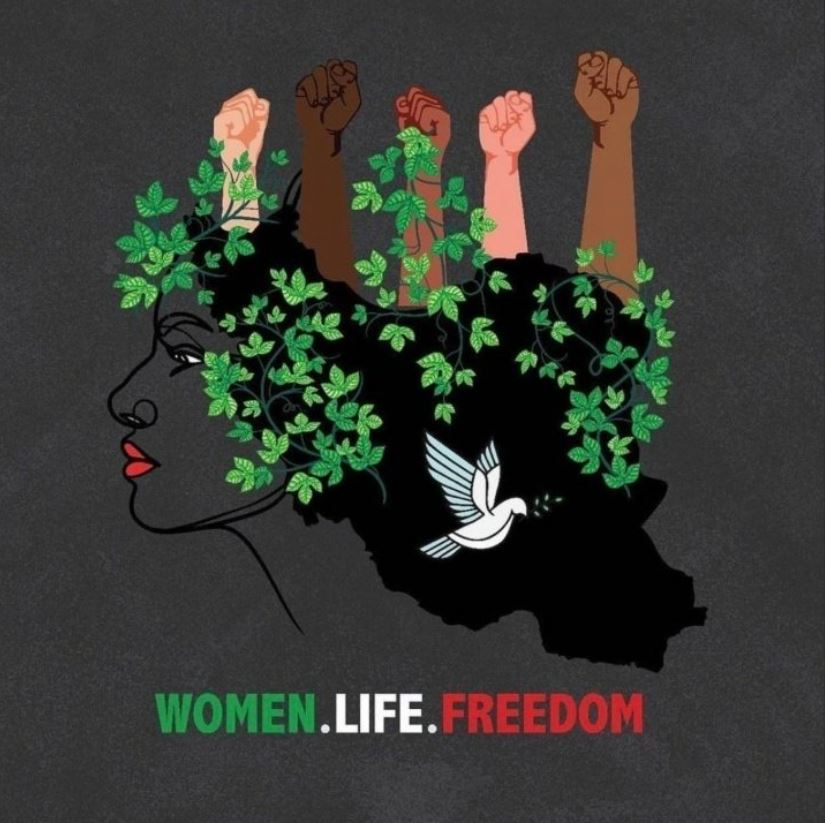

On the streets of Iran, women have been bravely burning their hijabs, cutting their hair, dancing, and chanting “women, life, freedom”. Not only are they demanding liberation from compulsory hijab, legally mandatory for all women and girls over the age of 9, but igniting wider debate about women’s rights, curtailed since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. Photographs and videos of these dramatic demonstrations have been shared widely across news outlets and social media sites, amassing thousands of likes.

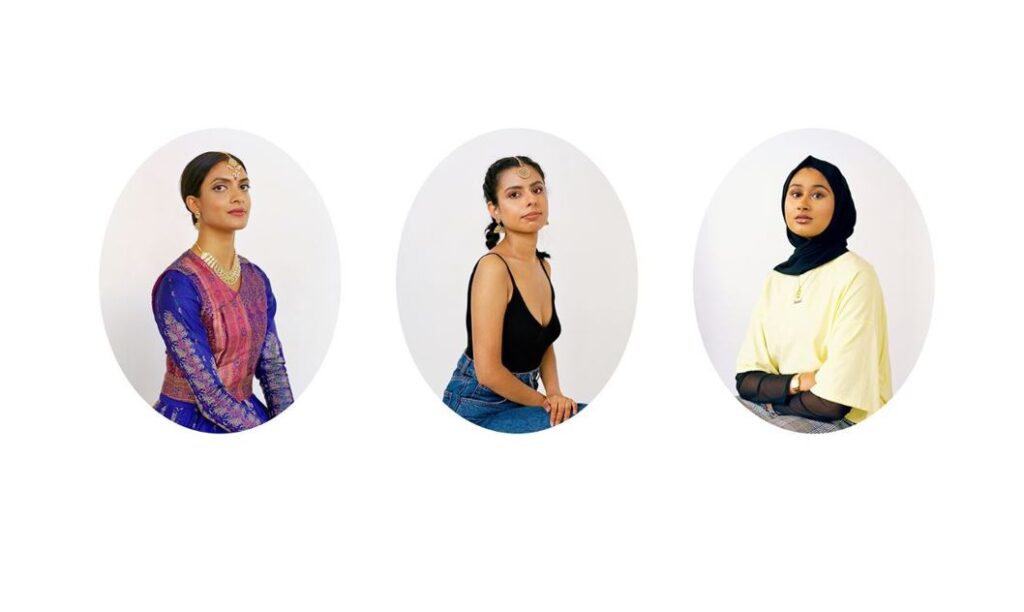

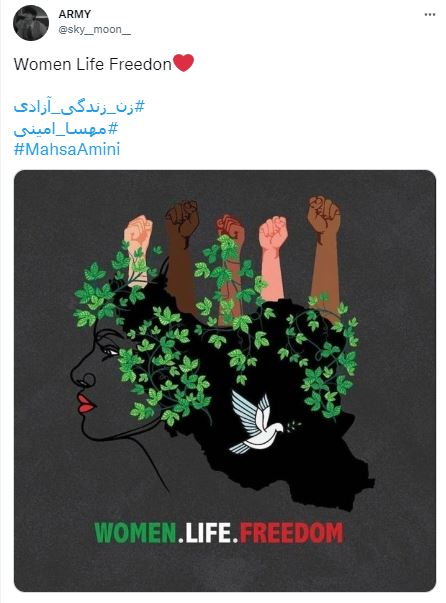

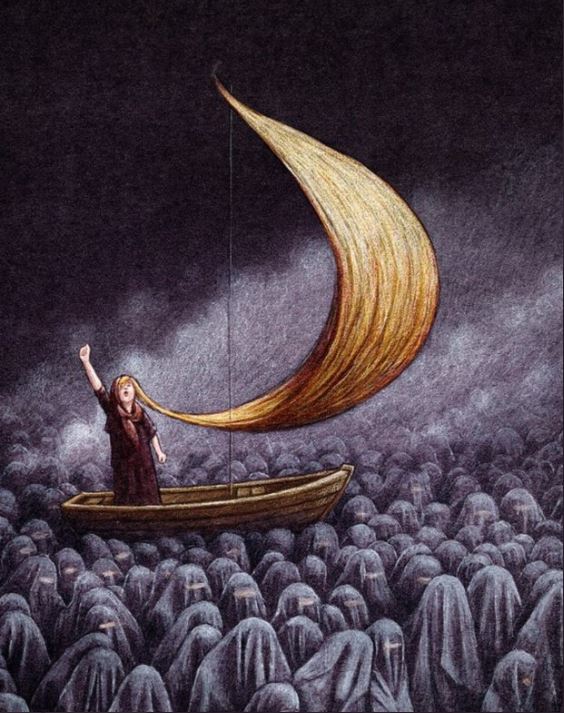

But, also being shared, and equally powerful, is digital protest art, much of it being made by women in Iran. Echoing, and illustrating, the fearless actions of countless protestors in public, the protest imagery depicts women wearing their hair free, or taking scissors to it, accompanied by the slogan ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ and #MahsaAmini.

Protest art has a long and significant feminist history, and these Iranian artists are using the same savvy tactics as women who have fought battles before them. While some of the artists are happy to have their name attributed to their work, others are uploading it namelessly, protecting their identity while acting as a unified collective, much like Guerrilla Girls, the anonymous feminist group devoted to fighting sexism and racism within the art world.

Their text and image-based artworks also recall the suffragettes in Britain, who used decorative banners, combining text and image, to share their message at demonstrations from the 1880s onwards. ‘DARE TO BE FREE’ is the slogan on one early banner; is this not the very same demand being made by these women today?

There were around 100 artists integral to the Suffragette movement, who worked as a collective to highlight injustices, raise public support and demand rights for women, including the right to vote. Among them was Sylvia Pankhurst, who created the graphic ‘Angel of Freedom’, blowing a trumpet. This active agent of change is not dissimilar from some of the female figures being digitally drawn today.

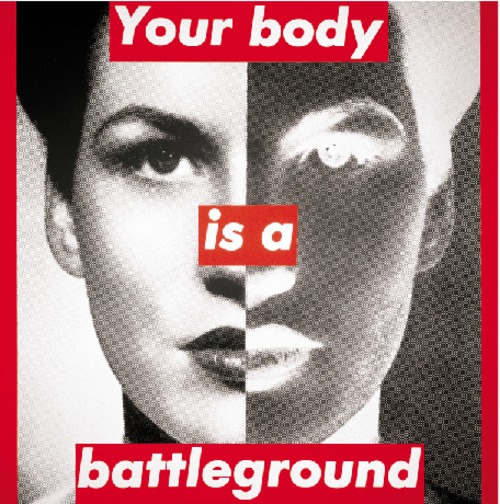

The emphasis on women centring, and cutting into, their own bodies also recalls reproductive protest art. In 1989, Barbara Kruger created ‘Untitled (Your body is a battleground)’ for the Women’s March on Washington to protest a new wave of anti-abortion laws and support women’s right to reproductive freedom. Juxtaposing black-and-white photograph with bold text, she subverted imagery of woman as an artist’s muse, instead framing her as an activist, carrying her own message, through her own body.

This new wave of feminist protest art for Iran’s women is also focused on the female body as a disruptive site for change and self-control. Taking scissors to the locks of their subjects, these women are cutting off the attribute of femininity, which has particular poignancy given the context – a woman’s hair is decreed to be hidden by the theocracy which rules them.

Throughout history, Iranian women have cut their hair as a sign of protest against an oppressor or to symbolise mourning. In The Shahnameh, an epic poem that recounts numerous myths and legends from Persian mythology, when the hero Siyavesh is killed, his wife and the girls accompanying her, cut their hair to protest injustice. Today, imagery of women cutting of hair marks both protest and mourning, given the death of not just Mahsa Amini, but over 100 other people, and counting, during the protests.

These artists are this historically symbolic imagery into a new realm, too – that of the male-dominated digital art world. To date, just 29% of those producing digital art are female and women artists account for just 5-15% of the multi-billion-dollar NFT industry’s turnover. However, OpenSea, the largest NFT marketplace, has been flooded with images titled ‘Mahsa Amini’. Many of these images are by women, and sales are now taking place with proceeds raised going towards United for Iran, a non-profit org working to empower the voices of women & girls in Iran. Other artists, including @Lunaleonis, have decided not to sell their NFTs, sharing them in protest and not for profit.

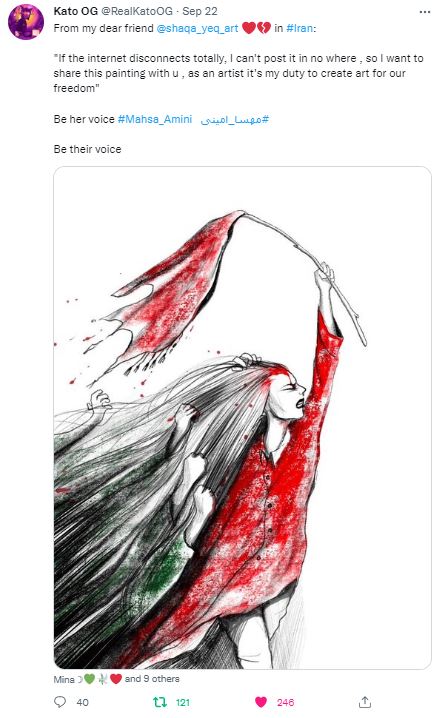

Whether they sell these images or not, with their protest art, these women artists are breaking boundaries in the digital art space. It’s a space which has Iranian authorities worried. In an attempt to curb this growing protest movement, Iran – which has often curbed internet freedom – has been enforcing restrictions. Over the last few weeks, it is reported to have blocked access to social networking platforms like Instagram and WhatsApp, and has shut off the internet in parts of Tehran and Kurdistan.

One Twitter user shared an artist’s work for her:

“From my dear friend @shaqa_yeq_art in #Iran: “If the internet disconnects totally, I can’t post it in no where , so I want to share this painting with u , as an artist it’s my duty to create art for our freedom” Be her voice #Mahsa_Amini #مهسا_امینی Be their voice.”

Iranian authorities are right to be scared, too, as many of the protest artworks are not simply raising awareness of their policing of women’s bodies, but acting as a real call to arms, just as we saw with the street art and murals for Black Lives Matter. International artists are now joining the movement, from Syrian/Iraqi artist Dina Razin, to Polish activist-artist Pawel Kuczynski and Marco Melgrati with his ‘Cut it out’ artwork.

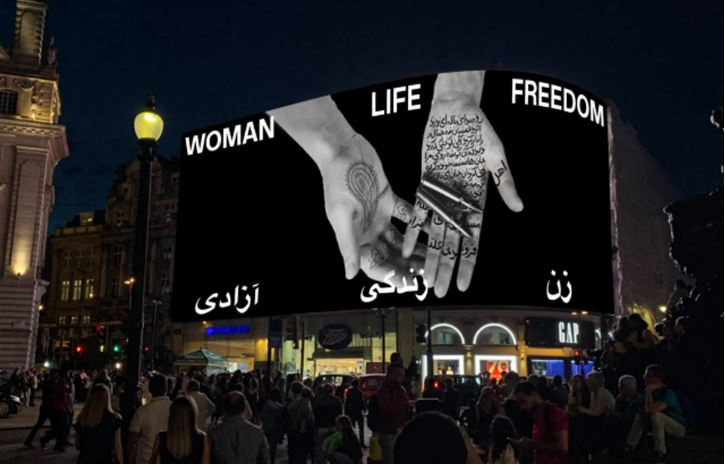

High-profile New York-based Iranian artist Shirin Neshat has also unveiled a digital art piece in London’s Piccadilly Circus and at Pendry West Hollywood in Los Angeles highlighting the deteriorating human rights situation in Iran sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini.

Neshat’s initiative, known as ‘Woman Life Freedom’ has been organised by the digital art platform Circa, and is accompanied by a time-limited print by the artist, with 50% of proceeds donated to the New York-based organisation Human Rights Watch.

Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, who spent six years in an Iranian prison, has also shared a video of herself cutting her hair in solidarity with the protesters. She has recently been joined, in this act, by a number of French actresses, including Juliette Binoche.

In digital artworks, protests on the streets of Iran, and in recordings such as this, the performative act of hair cutting has become the most important symbol in this women-led revolution which rails against existing power relations within Iranian society, while becoming a strong and unforgettable symbol for all women’s liberty.

As history shows us, protest art can have the power not only to condemn, but change, the status quo, and women, in particular, have used it as their weapon before. This is, undoubtedly, the next crucial chapter in feminist art history, in which activist artists are again turning to themselves as their own subject matter, and using their bodies as battlegrounds, with scissors as their symbol of struggle, rage and, ultimately, self-control.

While protest art is nothing new, in 2022 it is now infiltrating our feeds on social media, flooding digital art spaces and living on the blockchain, making it impossible for the world to look away from the crimes against women in Iran. But we mustn’t simply look and keeping scrolling; as internet access in Iran is denied, don’t we also have a duty to share these images? ‘Women, Life, Freedom’ is a simple and yet still radical aim for women today. Virtually standing side-by-side with them, let’s amplify their message; a retweet isn’t asking for much, is it?