The City of a Thousand Trades, Birmingham is well known for its industrial past. Far less well known, however, is its history as a centre for coding. But a new exhibition aims to change that: ‘Makers and Machines’ at Thinktank, Birmingham Science Museum celebrates local coders, past and present, while raising timely questions about the crossover between art and technology, and the impacts of Artificial Intelligence on creativity.

The exhibition dispels many myths. Among them, it shatters stereotypes that coding – writing instructions in a language that computers can carry out – is a man’s job. Instead, it profiles numerous female tech pioneers; among them, Dame Stephanie Shirley, who grew up in the West Midlands after arriving in the UK in 1939 as a five-year-old refugee. A talented mathematician, she set up her own software company in 1961, hiring only qualified women who had to leave employment because of caregiving responsibilities.

Another key figure in the exhibition is computer scientist Mary Berners-Lee, who has been overshadowed be her more famous son. After studying at the University of Birmingham, she collaborated with a team of pioneering women on the computer that in 1951 became the first in the world to be sold commercially: the Ferranti Mark I. As one of the world’s first freelance programmers, she worked as a home-based software consultant while raising 4 children; her eldest, Tim Berners-Lee, went on to invent the World Wide Web.

Originally from Stourbridge, Kathleen Booth is also given space for her story. This programming pioneer co-designed one of the oldest surviving electronic computers in the world, the HEC computer, which is a star of Birmingham’s internationally-significant collection of early British computers, and has recently returned to the city from long-term loan at Bletchley’s National Museum of Computing.

A more surprising masterpiece on show is a Morris & Co. sample of the ‘Dove and Rose’ textile. After all, didn’t William Morris rage against machines? A leading figure in the Arts and Crafts movement, the 19th century designer famously wanted to revive traditional handcrafts and skills as a reaction to the industrial revolution, and delivered lectures on the subject at Birmingham’s School of Art.

But, as the exhibition proves, it’s a common misconception that Morris was against all technology. A savvy businessman, he was interested in machine processes, including mechanised looms, when they could benefit the maker and quality of the work. A fan of precise processes, he once said, “Remember that a pattern is either right or wrong. It cannot be forgiven for blundering, as a picture may be which has otherwise great qualities in it.”

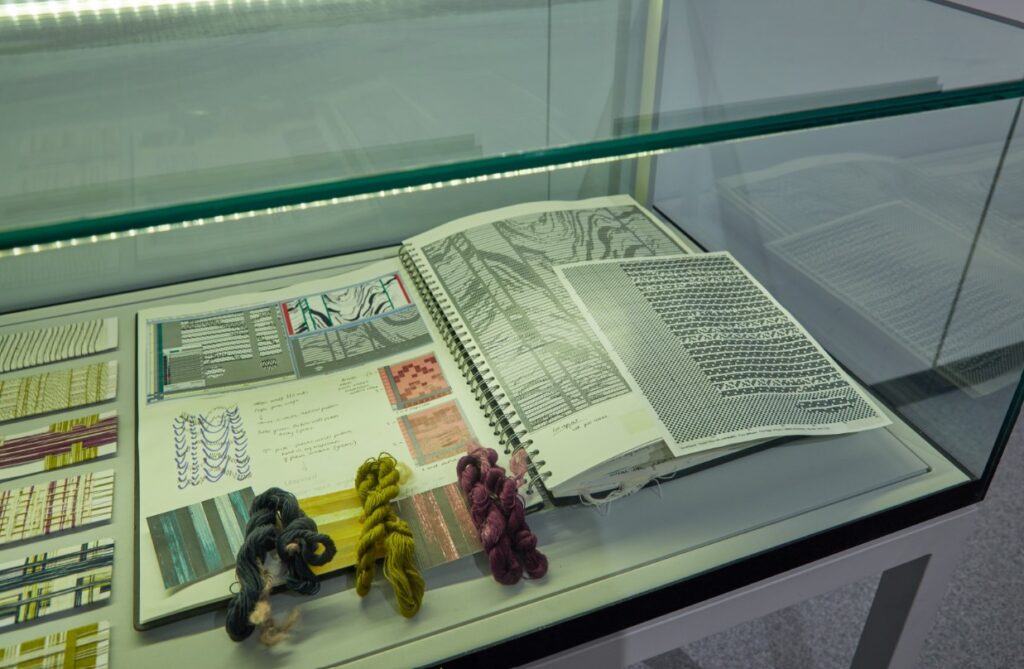

Proving his point, the intricate Morris & Co fabric on display was woven on a Jacquard loom. By its side is the original watercolour design, annotated with instructions for turning it into a thread-by-thread pattern for the weaver, called a ‘point plan’, which can be read as an early example of coding.

Comparisons are drawn with contemporary artists, including Sachi Shetty, Alexandra Woolner and Emily Jayne Higgs, whose digital pattern-making work is exhibited. Also featured is game designer Zafar Qamar, who speaks of games “as a form of art”, given “the layers of code and creativity” involved. As artists increasingly embrace the use of technology, it’s interesting to think what William Morris would be like now. Would he be playing around with the AI image-generator DALL·E?

Carrying a crucial message, the exhibition challenges binaries – too often we separate logic from artistic skill, and maths from imagination. Instead, it visualises the crossover between them, presenting coders as makers, and makers as coders, and all as creatives. As the exhibition’s curator Felicity McWilliams explains:

“Teachers told us that their students often see technological and creative careers as opposites of each other, that they feel they have to make a choice between them. Makers and Machines is designed to disrupt that idea. We want visitors to take away the message that tech industries have always relied on creativity in the same way that creative industries have engaged with new technologies.”

At a time when the art world is raising questions about the implications of AI, the interactive exhibition invites visitors to share their opinions on the subject, with a wall of challenging questions, as opposed to answers; among the most poignant: ‘What impact do you think Artificial Intelligence will have on human creativity?’

In a clever twist, curators also reveal that several captions in the exhibition were created using AI, asking visitors if they can spot the three labels written by a chatbot. Crediting, rather than concealing, the use of technology is essential in this new era of digital revolution, as evidenced in this disruptive, thought-provoking exhibition. Problems will only arise when its use, and the creatives behind it, are not acknowledged. Could this column, for instance, have been written by AI?

Entry to ‘Makers and Machines: creativity in the computer age’ is included in the price of entry to Thinktank.

This article was originally published in the Birmingham Post and Mail.

Great review of the exhibition. We had a blast working on the design and graphics. #designedbypenguins