Recently, there’s been a shift towards immersive exhibitions, which allow viewers to step into 360° paintings or listen to soundtracks that tell an artist’s story. I’ve enjoyed these experiences to varying degrees, so was intrigued by the sound, or should I say smell, of ‘Scent & the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites’ at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts. The gallery was promising “a delight for the senses – both visual and olfactory”, thanks to a collaboration with perfume house Puig. But would inhaling aromas add or detract from looking at the art?

At the entrance to the exhibition, I was greeted by Evelyn de Morgan’s ‘Medea’, from 1889. In ancient Greek mythology, the sorceress uses her magic powers to help Jason find and retrieve the golden fleece. But, upon discovering that the hero has been unfaithful, Medea takes revenge by murdering their two sons. In de Morgan’s painted version of events, she stands tall, in a sweeping, dark fuchsia-coloured gown. Alone in a corridor, she’s framed by extinguished lamps, which emit their last curls of smoke, symbolising her own dark thoughts. In her hands she holds a vial of iridescent potion, from which violet fumes rise.

It’s a potent and compelling opening to the show, which took me by surprise. I’d been expecting portraits of pretty young maidens smelling rose petals, with sweet fragrances to match. Instead, the exhibition reflects a far wider range of scents and their associations. Among them are the long-established anxieties around the sense of smell as a harbinger of physical and moral corruption – as Medea’s deadly mixture represents.

Such surprises are thanks to the rich curation and expertise of Dr Christina Bradstreet. Having spent more than twenty years researching the symbolism of scent in Victorian era paintings, and recently authored Scented Visions: Smell in Art, 1850-1914, this exhibition is an illustration of her findings.

As part of her research, she has explored Miasma theory, the idea that smell can cause disease. This underpins several paintings, including John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s ‘Thoughts of the Past’, 1859. He created it in the year of the ‘Great Stench’, when hot weather intensified the smell of untreated human waste that poured into the River Thames – to such a degree that Parliament closed early.

Given recent news of sewage being released into British rivers and seas, the painting carries a contemporary relevance. Moreover, as Bradstreet points out:

“Many of the themes that emerge in relation to smell in Pre-Raphaelite art resonate with us today. Having lived through the Covid-19 epidemic we, like the Victorians, have felt the fear of an invisible deadly force (be that a virus or stench) invading our spaces and bodies, to devastating effect”.

This painting’s aroma carries with it another meaning, too. An open window in the picture suggests the infiltration of the stench into a sex-worker’s parlour, aligning the ‘fallen woman’ with the foul river.

Smell carries another moralising message in Simeon Solomon’s ‘A Saint of the Eastern Church’, 1867-68. An alluring, haloed young man wears a tunicle, traditionally worn during Catholic Mass. In his right hand, he holds a large sprig of myrtle, which was typically given to bridegrooms as an aphrodisiac on their wedding night. In his other, he bears a smouldering censer of incense, which was banned in Anglican ceremonies. At a time when homosexuality was illegal, and Solomon was himself arrested for sodomy, the portrait is dense with symbolism of forbidden male love and same-sex desire.

This is one of the show’s paintings that viewers can experience at an extra dimension, by releasing a bespoke scent into the air. Pressing the button on a nearby diffuser, I inhaled notes of myrtle, white flowers, and dark amber, which evoked the incense-filled air of the Solomon’s scene.

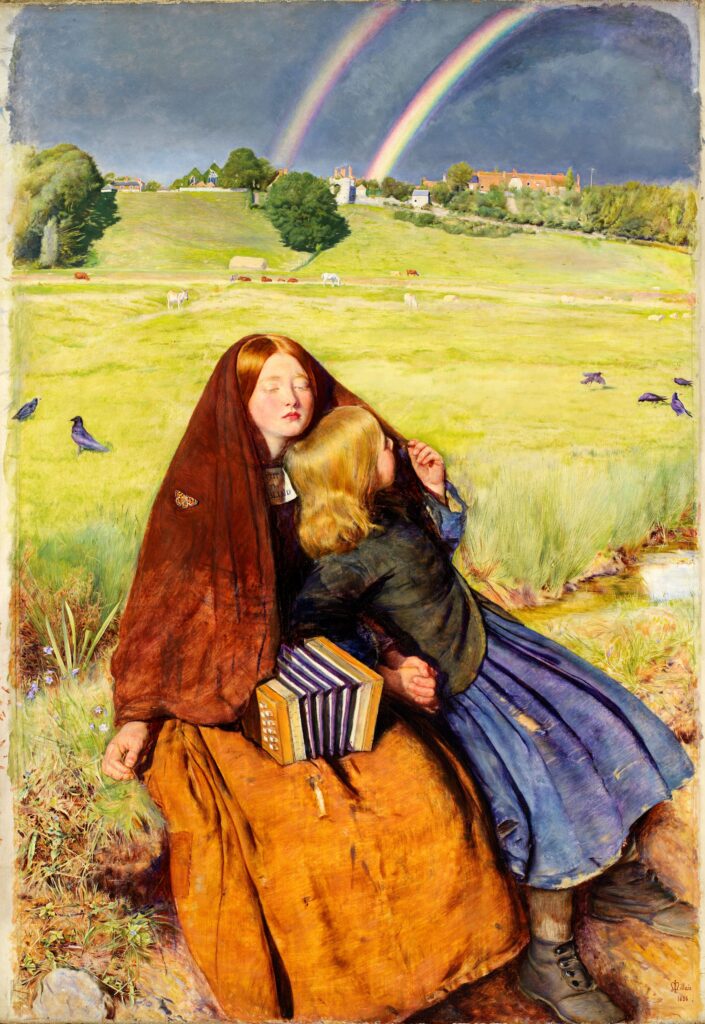

Next, I diffused two more scents associated with another painting – John Everett Millais’s ‘The Blind Girl’, 1856. It’s a work I have stood before on countless occasions at Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery, from where it’s on loan. But this interactive experience made me look at it in a brand-new light.

The first of the perfumes evoked the aromas of freshly cut grass and earthy flowers, which the blind girl cannot see but can smell, as she sits upon the meadow, below a double rainbow. As I released the scent, I was transported back to my own childhood, playing outside, before returning to the painting to empathise more fully with the sitter. Noticing that her nose was tinged pink, I could almost feel the freshness of the spring air.

My eyes also moved to the blind heroine’s younger sister, who snuggles into her older sibling’s damp, yet comforting, shawl – this item of clothing has inspired a second, more musty scent that I released from the diffuser. It made me experience the scene from the perspective of a character, whom I had previously overlooked.

Professor Jennifer Powell, Director of the Barber, hopes that “the show will enable audiences to connect with Pre-Raphaelite paintings in inspiring new ways.” I found this to be true.

While gimmicky technology can at times detract from the act of looking at real-life paintings, on this occasion it made me slow down. By inhaling the artworks’ imagined aromas, I engaged with them more fully. An evocative, multi-sensory exhibition, Scent & the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites has real depth and hits all the right notes.

Developed in collaboration with Artphilia, the storytelling art curators, and Puig’s AirParfum olfactory technology, Scent & the Art of the Pre-Raphaelites is free to attend and runs until 26 January 2025 at the Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham.