The British Museum is currently home to goddesses, demons, witches, spirits and saints. These divine and demonic figures, feared and revered for over 5,000 years, are the protagonists of an exhilarating new show, ‘Feminine power: the Divine to the Demonic’. But, what exactly is femininity? And, at a time when the word woman is a point of contention, did the curators dare to define it?

Art history is filled with images of anonymous, passive and beautiful females reclining for the male gaze. This narrow definition of femininity, tied to a woman’s sexuality, is still dominant in Western society today; just take a look at Instagram. But, this show proves that anthropology and ancient history are defined by powerful women, many of whom are named. And clothed.

Rather than being arranged in neat chronological order, the exhibition is cleverly arranged across 5 themes, including Creation and nature, Passion and Desire, Magic and Malice. This refreshing approach means that around every corner are surprising pairings, across cultures and contexts, which we can learn valuable lessons from.

Opening the show are female figurines, created between 10,000 and 4,000 years ago, from the Jordan Valley and Cycladic Islands. While their meaning is unclear, they show the importance that many early societies attached to a femininity, rooted in a woman’s body, and elevated motherhood.

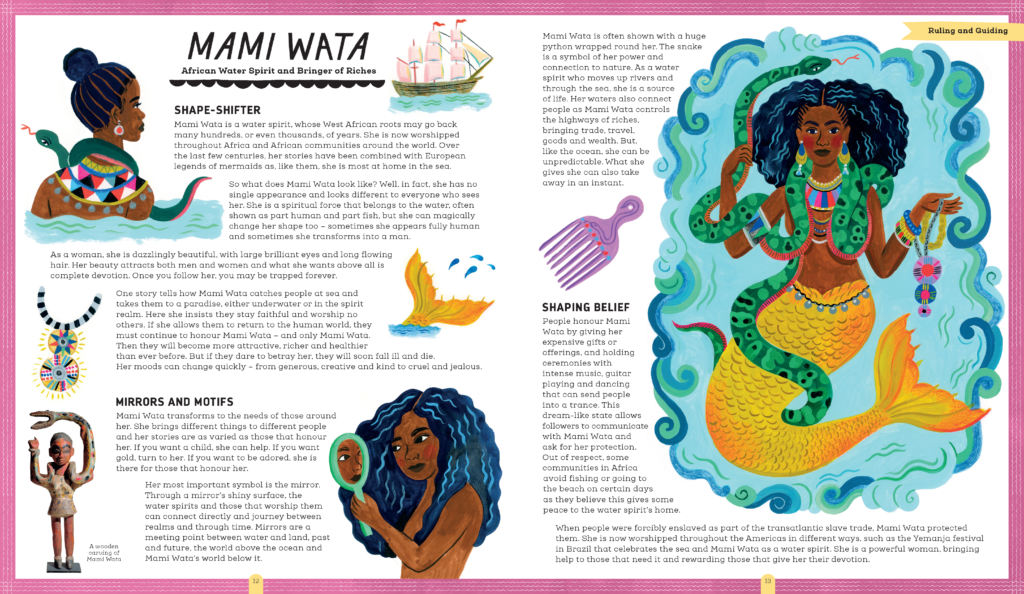

Female power has often been associated with nature, and many cultures see the earth as a maternal force. In Greek mythology, Gaia is the personification of the Earth. But femininity is undoubtedly full of contradictions, and the exhibition celebrates this. Embodying the complexities of femininity is Pele, the Hawaiian goddess of volcanoes, who both destroys the land with her lava, while in doing so enables growth and regeneration.

The exhibition also shines a light on femininity as a social construct, separate from biological sex; it differs according to different cultures and societies. There’s the lion-headed Egyptian goddess Sekhmet, known for unleashing violence or engaging in war, a realm more associated with men. There’s the Hindu warrior goddess Durga, worshipped for her supreme wisdom and fearlessness. There’s Tlazolteolt, the Huaxtec goddess of purification, who inspires sexual desire and eats filth to cleanse transgression.

A highlight of the show is John William Waterhouse’s 1891 painting of Circe. The painting depicts a scene from the Odyssey in which the sorceress Circe offers a cup full of potion to Odysseus, whom she intends to bring under her spell, as she has already done with his crew – now turned into pigs, who sit compliantly at her feet. More could be discussed about the ways in which women, past and present, use their sexuality as a force of dominance and control over men, including when it’s their only option, as has often been the case throughout history.

This show also missed a trick by not including representation of the muses – in ancient Greece, these 9 feminine divinities were the source of inspiration for poets, writers, musicians and artists. They appear on pottery, as well as in paintings, as the embodiment of creativity and wisdom. In fact, the Greek word for museum, ‘Mouseion’, means shrine of the Muses. So much female power has thrived in the form of influence and inspiration, as it continues to do today. Where would artists be without their muses? And the BM owes its name to them!

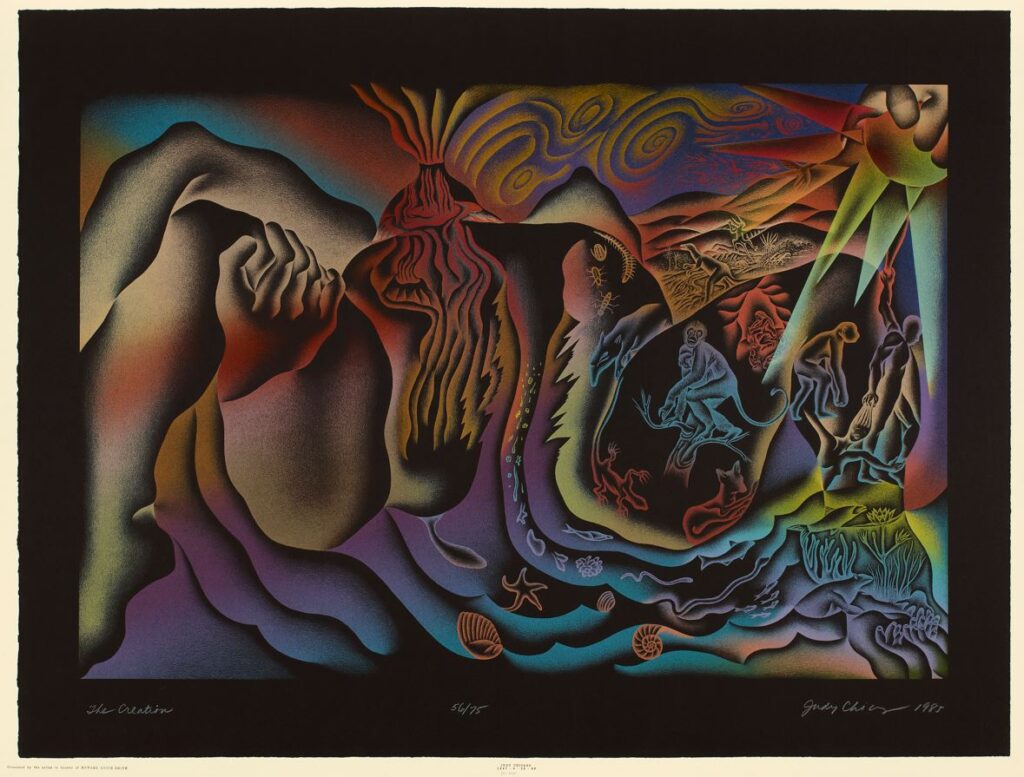

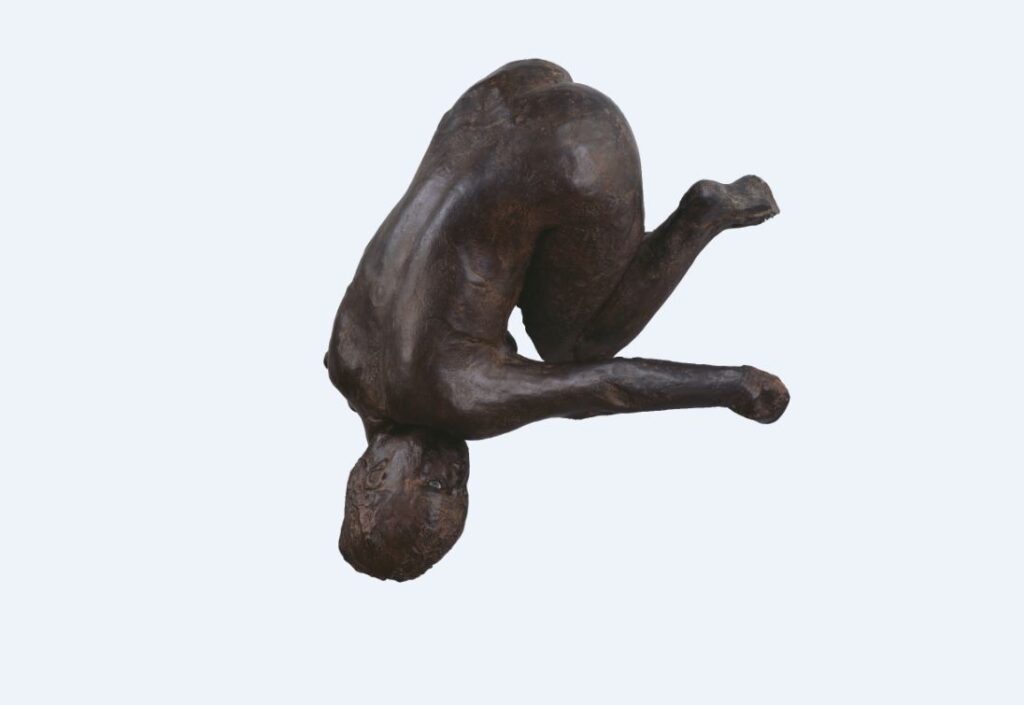

Woven into the exhibition are several modern and contemporary art works, from Judy Chicago’s ‘Creation’ (1985) to Kiki Smith’s primal sculpture of Adam’s first wife, ‘Lilith’ (1994). These are a real treat. In fact, the show would have felt more radical with a wider range of current imagery. Which women hold feminine power today and what does that look like? Where’s Beyoncé, for example? In photoshoots, on stage, and in music videos, she plays with symbolism of divine femininity, dressing herself as Yoruba goddesses, as well as the Virgin Mary.

Instead, the BM has brought in contemporary and cultural commentators, including Elizabeth Day, Mary Beard and Bonnie Greer. Quotes from their point of view are embedded in the exhibition labels. But, too often, they are talking about their own choices (for instance, deciding not to have children) or vaguely discussing the feminine, rather than adding any real value and depth to the interpretation.

“Across time we have needed to look at this state of being, this reality called feminine”, reads one vacuous text. What does this even mean?

And another: “I’m a feminist but some mornings I’m feeling divine, other mornings I feel demonic. But I always try to stand in my feminine power, so this exhibition is very much for me. Come with me, let’s find our divine, demonic feminine power together!”.

I’m not a fan of this populist Netflix-styled talking heads addition, which falls into the trap of always making femininity about the personal. Surely, the audience (both men and women) can be left to relate to the featured goddesses on their own terms?

However, this is nevertheless an empowering exhibition which proves that there has always been, and still is, great force to the many versions of femininity. It’s something men have attempted to control and condemn, as the presence of a Malleus Maleficarum, the infamous witch-hunting book, from the late 15th century, shows. But it’s also clear that femininity cannot be bridled.

Given an impossible task, of ordering femininity into a single exhibition, the curators have done a great job of presenting a complex, layered narrative of feminine power through a diverse collection of objects, artefacts and artworks, without fetishizing femininity.

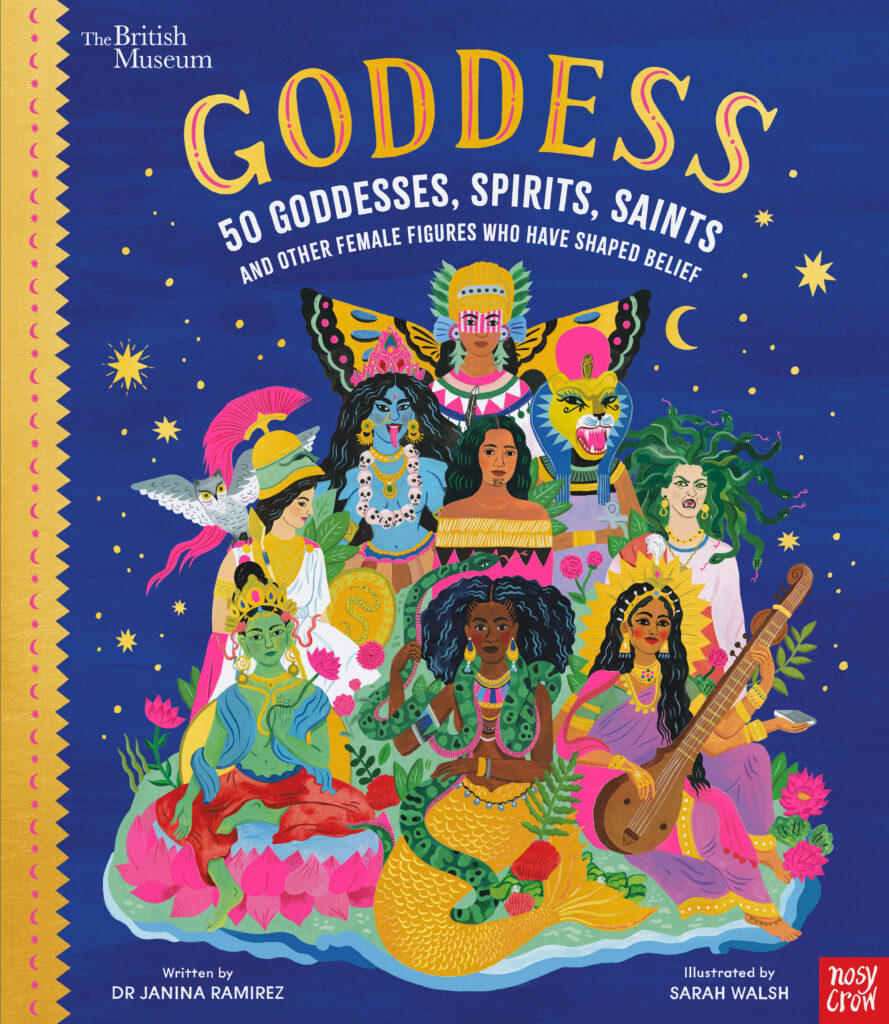

It also concludes with a tempting shop, filled with brilliant books on feminist art history, archaeology and mythology. Among my favourite titles was this colourful children’s book, featuring 50 inspiring goddesses, spirits and saints, published by Nosy Crow.

At a time when the word woman has been caught up in the advancing culture wars, this show succeeds in dividing biological sex from gender roles, defining ‘feminine power’ as a broad and complex construct, which varies across times and societies. Femininity can be violent and chaotic, creative and inspiring, terrifying and maternal. Visual culture – in the form of masks, sculptures, figurines, paintings – demonstrates this far better than words will ever do.

This is a truly fascinating and exhilarating exhibition, which proves that there is no one form of the feminine, but hybrid femininities, which exert power in many, mutable forms. And to explore even more visions and versions of femininity, there is, of course, the rest of the British Museum.

Feminine power: the divine to the demonic runs until 25 Sep 2022 at the British Museum in London.

Thank you for your review and pictures. I live in the US, hence won’t be able to see exhibit, but this is a great substitue!