Heavy art books are crammed onto a tall bookcase in Tom Hicks’ Wolverhampton studio. More are stacked in neat piles on his desk, where his recently published photobook also sits. Taking its title from the pseudonym he uses to share images on social media, ‘Black Country Type’ features 142 photographs which frame the post-industrial landscape of the region in a new light.

Since 2017, Hicks has been challenging negative views of the Black Country, where he has lived all his life. With a strong emphasis on colour, he focuses on words, typography, handmade lettering and shop signs: ‘Beds Beds Beds’ reads one; ‘Porky’s Pantry’ another. There’s a wry sense of humour to the scenes he captures with his camera phone. ‘Loads more brooms inside’ is the yellowed advert propped up before 15 wooden brooms, poking their bristly heads out.

He also photographs ‘types’ of architectural features, objects and structures, always under sunny skies. In Hicks’ world there’s no need for filters: “when the sun is on a building, it lights it up”. I meet Hicks on a Black Country Type of day – the sky is cloudless and blue above Wolverhampton Station, where he’s just been up on the car park roof to take photographs.

From the station, we walk down several back alleys to his studio, along his preferred route: “the backs of buildings are more interesting that their fronts”, he tells me, adding that Lucian Freud’s paintings often include scenes through a window framing the rear of an apartment block to create intriguing backdrops.

It’s these urban backgrounds which Hicks brings to the fore, while hinting at human presence without including a single figure in his frame. He takes inspiration from great painters of derelict and graffiti-scrawled sites, including George Shaw and Jock McFadyen, having amassed a wealth of art historical knowledge through his job as an art librarian at the University of Wolverhampton.

But it is the medium of photography which best allows him to synthesise his interests in architecture, typography, design, art, history and music. The square format of Hicks’ images also points to his early love of vinyl records and their original cover art. He remembers visiting Birmingham on the no.9 bus to order new releases from the now-demolished Central Library, borrowing them for weeks at a time.

For years, the “inherent beauty in Birmingham’s industrial surroundings” has inspired the photographer. Overlooked streets and signs in the city centre, from Needless Alley to cracked doorways in the Jewellery Quarter, have captured his imagination. “Traces of 60s architecture, bits of art deco that are hidden away, derelict-looking windows which front workshops” have all become his subject matter, as he hints at the area’s heritage and history, its people and manufacturing past.

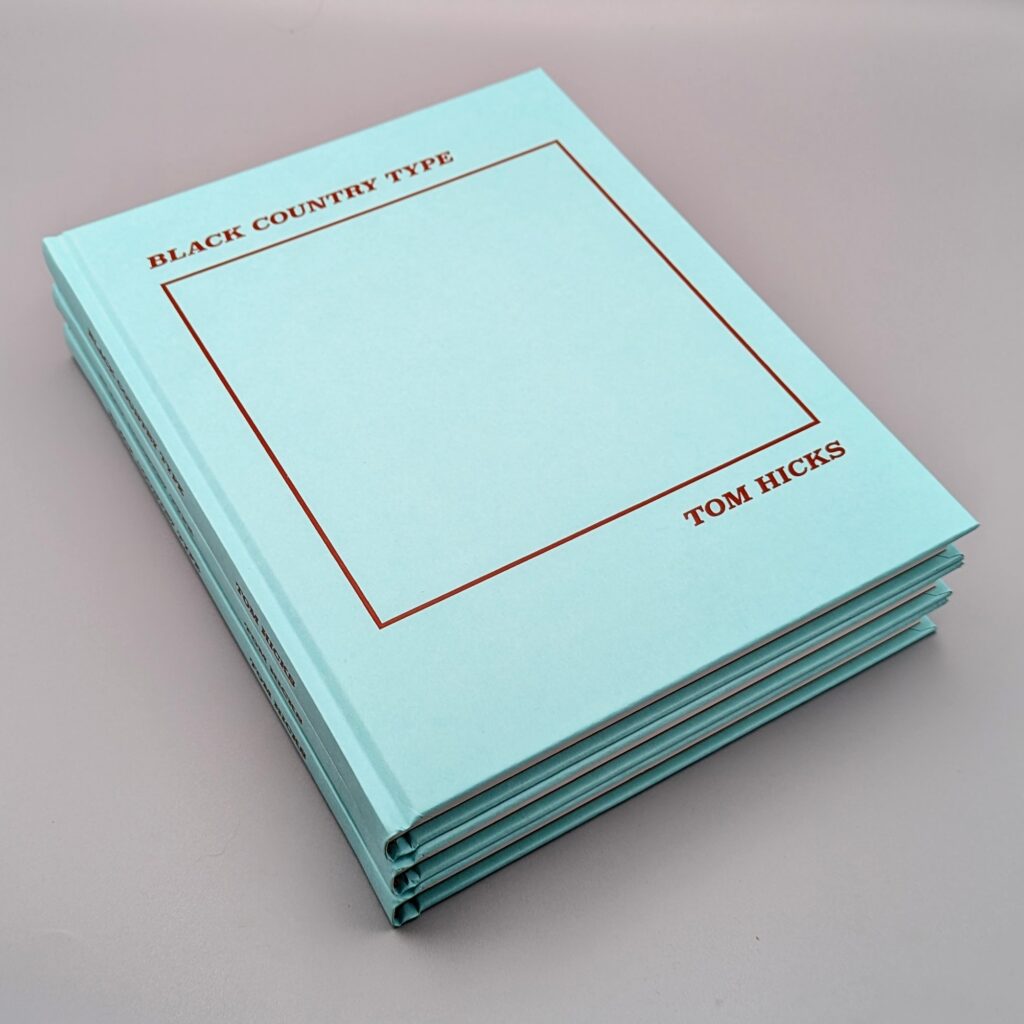

The city does hold a deep personal significance for Hicks, too, as his grandparents moved from Ireland in the late 1940s to work at Fort Dunlop. “That factory is the reason I am here”, he says. Factory catalogues from the Black Country have also defined the look of his photobook, which mirrors their minimal aesthetic, with only a name on its striking mint green cover, inviting readers to look inside and discover more.

Although he’s taken tens of thousands of photographs across Birmingham and the Black Country to date, the book displays only a considered selection, arranged according to colour and shared aesthetics, as opposed to geographical boundaries. It takes readers on a winding journey, much like the unplanned ones that Hicks makes himself, deliberately getting lost on a free-form walk through an industrial estate or hopping off his bike to snap a shutter that catches his eye, at times getting in trouble for taking people by surprise.

“Sometimes I get asked if I’m from the police or the council”, he says, remembering one resident pulling up their shutter to demand “What are you doing?” as he framed their window with his camera phone. On another occasion, he turned around to find a squad car of 6 police men watching him with curiosity. After explaining what he was doing, they stood down, and one has become a loyal follower of his Instagram account @BlackCountryType.

Although figures are deliberately absent from his photographs, Hicks loves people and is happy to share his process with them on photowalks. Part of his process is also allowing for reactions from, and conversations with, viewers. While some people identify with the locations – shops, cafés and factories – as they remember them in their heyday, others are intrigued by the geography: “What part of Italy is this?”, one viewer asked, surprised to hear, “It’s Stourbridge” from Hicks.

Acting as a great and playful portrait of the region, Black Country Type folds together Hicks’ photographic impressions in one place, for the first time. Worthy of a place in every art library, this brilliant book layers past and present, fonts and facades, sharing the backdrops which act as the fabric in our everyday lives. Through his lens, Hicks invites readers to recognise overlooked beauty and take pride in this colourful place we get to call home.

The Black Country Type book, as well as signed prints, are available from Ikon Gallery’s shop.