Before artists applied paint from tubes, they created pigments from the natural world. Plants, flowers and rocks inspired the colour palettes and materials they used to make masterpieces and manuscripts. Among them, the Birmingham Qur’an, as I recently learnt during a day of creative workshops at Birmingham’s Botanical Gardens.

‘Inks, Pigments and Plants’ was a special, and sold out, event devised by The Museum of Islamic Arts & Heritage (MIAH) Foundation and Birmingham Botanical Gardens, in partnership with Culture Forward at the University of Birmingham.

On a crowded table were rows of pots and jars, filled with handmade dyes and powders, alongside a pestle and mortar, and papers stained myriad colours. Behind them, stood Dr Neelam Hussain, Director of the MIAH Foundation and Curator of Middle Eastern Manuscripts at the University’s Cadbury Research Library. Over the course of the day, she shared her expertise and knowledge with nearly 100 attendees, holding their attention through her engaging style.

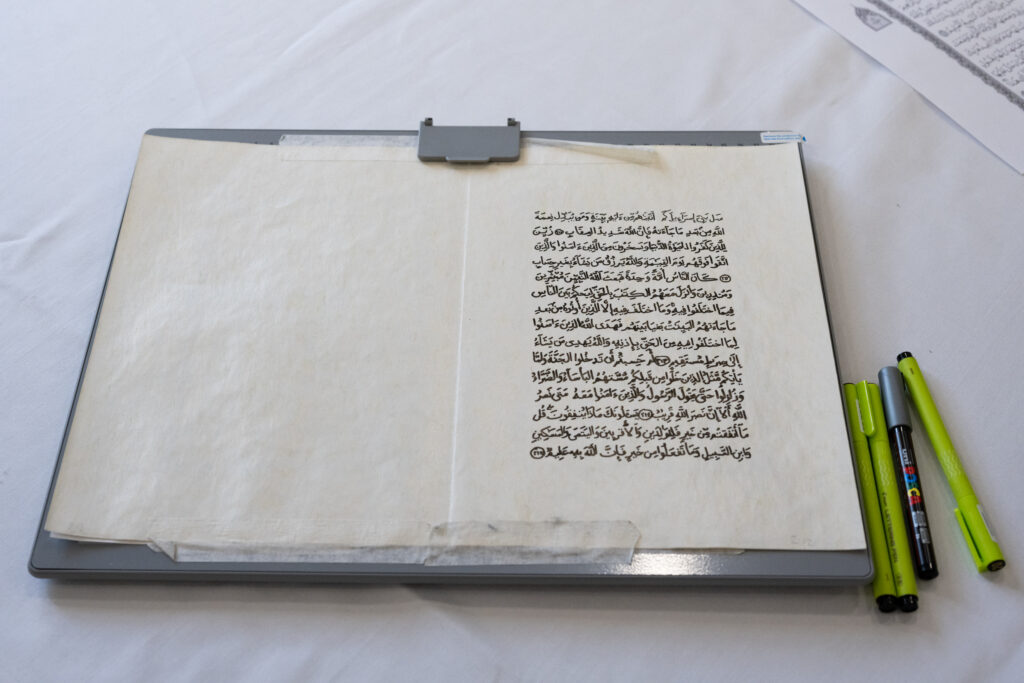

We were told that “Manuscript means ‘written by hand’”, and these precious objects hold “a rich tradition of craftsmanship”. There are over 3000 exquisite examples held within The Mingana Collection at the University, which is where the Birmingham Qur’an can be found. In contrast to today’s published books, “every single one is unique and has its own history, holding the imprint of the artists who decorated them with different materials.”

Among those materials are dyes, inks and pigments, cast from the raw colours extracted from plants, which Hussain had recreated, like an alchemist. She showed us how turmeric and saffron can be combined to create a beautiful orange blossom colour, and Sepia-coloured ink can be cast from crushed walnuts steeped in water. Hibiscus flowers, meanwhile, can be used to make a deep purple stain, which she invited attendees to test on thin strips of paper.

Medieval artists from the Islamic world looked to nature for ways in which they could dye and decorate paper, including pages of the Qur’an. As they only had their local environments to work from, Hussain explains that “we can sometimes identify where manuscripts were made based on the colour palettes employed.” The beautiful Lapis Lazuli blue originates from rocks in Afghanistan, for instance, and was used most heavily in nearby regions.

Such knowledge can be applied more widely, too. We can see in the great landscape paintings of Romantic artist John Constable his signature use of chrome and ochre yellows from the British earth – colours act as clues, indicating where artworks were created.

The Qur’an, as well as being a holy book, can be looked upon as an artwork with a focus on beautiful calligraphy in the earliest manuscripts from the 7th century. Later manuscripts in Birmingham’s Mingana Collection are defined by their floral and biomorphic borders, hand-painted motifs and illuminated frontispieces.

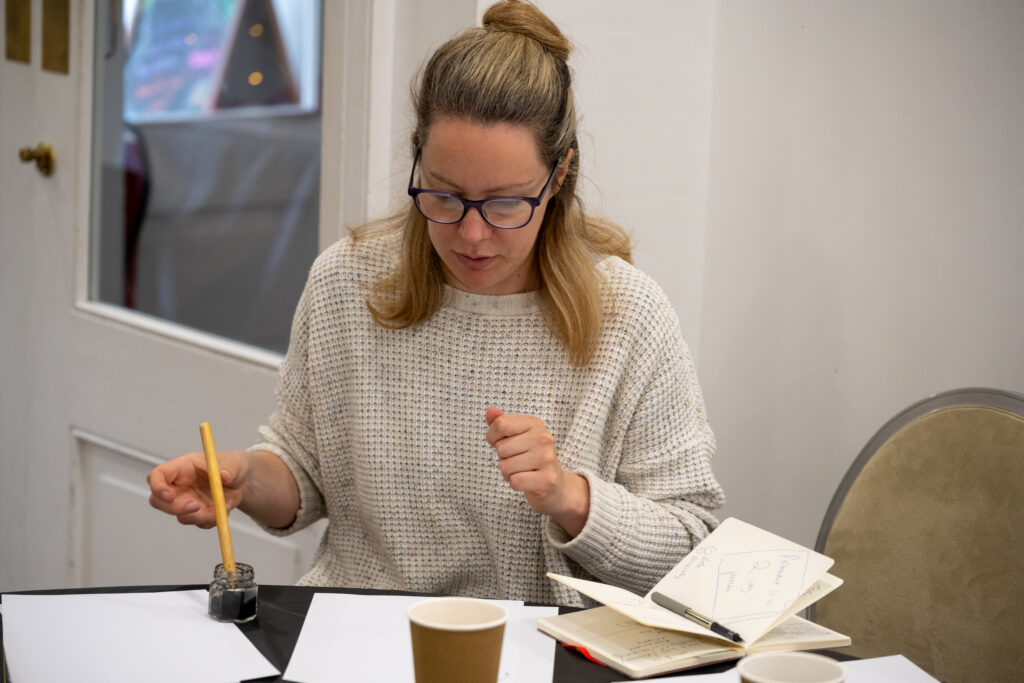

During the day, we not only learned about the magic of making manuscripts from natural materials but were invited to put into practice what we had learnt during several workshops delivered by MIAH’s resident practising artist, Areeba Ammad.

I loved the opportunity to try my hand at calligraphy, using a bamboo reed pen and black ink made from oak-soaked silk fibres to draw the Arabic alphabet. “This is bringing back memories of reed drawing at home”, I overheard one woman tell a friend, while for me it was a new type of artistry.

Sat around the table were adults and children from across Birmingham, as well as Coventry and Cambridge, and from a diverse range of cultural backgrounds. Some had previously visited the Botanical Gardens, while for others this was their first time, having heard about the event through MIAH.

In the same room, we were also invited to contribute to a new Birmingham Qur’an, tracing the Arabic scripture from pages laid on light boxes, which was a meditative act, regardless of beliefs. Collectively, the community will transcribe 6,000 verses, as part of a wider ‘Qur’an in the City’ project, while the book’s front cover will be designed using inks and pigments inspired by locally sourced plants at Birmingham Botanical Gardens and Winterbourne House and Gardens.

Finally, the day included an opportunity to enjoy a supported trail through the Gardens to find the very plants that were once used to create inks, dyes and pigments, including hibiscus flowers, rose petals and indigo. Within the humid tropical house, a papyrus plant could also be found.

I am strong believer in using creative activities to bring history to life, which is exactly what MIAH achieved through their specially curated and interactive day at the Botanical Gardens in Birmingham. It was inclusive of all faith groups, and knowledge was shared generously within the welcoming green spaces.

“We want to engage less advantaged communities and wider groups, while combating isolation through art”, explained Iqra Fayaz, who is MIAH’s Cultural Learning and Participation Officer.

This event was part of a wider programme, established by MIAH with the aim of promoting awareness and understanding of the history, arts, culture and heritage of the Islamic world, as well as the history of Muslims in Britain and Europe.

I am definitely tempted to sign up for their Calligraphy Club, and while I’m at it, the Islamic Art and Architecture Course, so I can learn more about the magical arts of the Muslim world, where artists drew on nature for their creativity.

Culture Forward is increasing engagement with the University of Birmingham’s cultural collections, such as the Birmingham Qur’an. More events can be found at www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/culture-forward

Birmingham Botanical Gardens are open for everyone to visit seven days a week. Find out more and plan your visit here.