Who were the female sculptors who worked with Rodin? A moving new body of work and exhibition by Rebecca Fortnum, ‘Les Praticiennes’, shines an important light on 15 overlooked female sculptors from Rodin’s studio, whose names and stories deserve to be shared.

Today, the talented French sculptor Camille Claudel (1864–1943) is known primarily as the muse of Auguste Rodin, rather than as an artist in her own right. Yet during her lifetime, she was not only Rodin’s pupil and model but a significant collaborator; inside his studio she worked side-by-side with him on complex commissions and in creative dialogue, while also developing her independent practice. Claudel’s story is not an isolated one, as a new exhibition shows. Through ‘Les Praticiennes’ at the Henry Moore Institute, Rebecca Fortnum has painted and drawn 15 overlooked female sculptors from Rodin’s studio back into art history.

The project has emerged from Rebecca Fortnum’s research into the female sculptors associated with Rodin and his studio in 19th century Paris, during her fellowship at the Institute. As they were not able to enter the École des Beaux-Arts until 1887, women wishing to become professional artists often studied at a private academy before apprenticing with a ‘master’, and, for the most part, encountered prejudice in their working lives.

Rodin devoted significant time to training women to sculpt, and sometimes went on to employ them in his studio as a praticienne or assistant. As women determined to make art against the odds, each of the artists Fortnum has selected to make work from has an extraordinary, and in most cases unpublished, life narrative.

The 15 female artists Fortnum has rediscovered are: Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923), Malvina Hoffman (1885–1966), Kühne Beveridge (1879–1944), Camille Claudel (1864–1943), Hilda Flodin (1877–1958), Sigrid af Forselles (1860–1935), Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877-1968), Anna Golubkina (1864–1927), Madeleine Jouvray (1862–1935), Jessie Lipscomb (1861–1952), Clara Rilke-Westhoff (1878–1954), Bessie Potter Vonnoh (1872–1955), Ottilie MacLaren Wallace (1875–1947), Emilie Jenny Weyl (1855–1934) and Enid Yandell (1869–1934).

Rebecca has uncovered interesting stories behind each piece in the show. For example, Sarah Bernhardt (1844–1923) was the most famous actress of the time and a muse but less known as an accomplished artist. Meanwhile, Meta Vaux Warrick Fuller (1877–1968) who experienced both sexism and racism when she arrived in Paris in 1899, used sculpture to celebrate Afrocentric themes and worked at the fore of the Harlem Renaissance.

Together these female sculptors constitute an astonishing web of friendship, association and influence from all over the globe, including England, Scotland, France, Russia, Germany, United States and Finland.

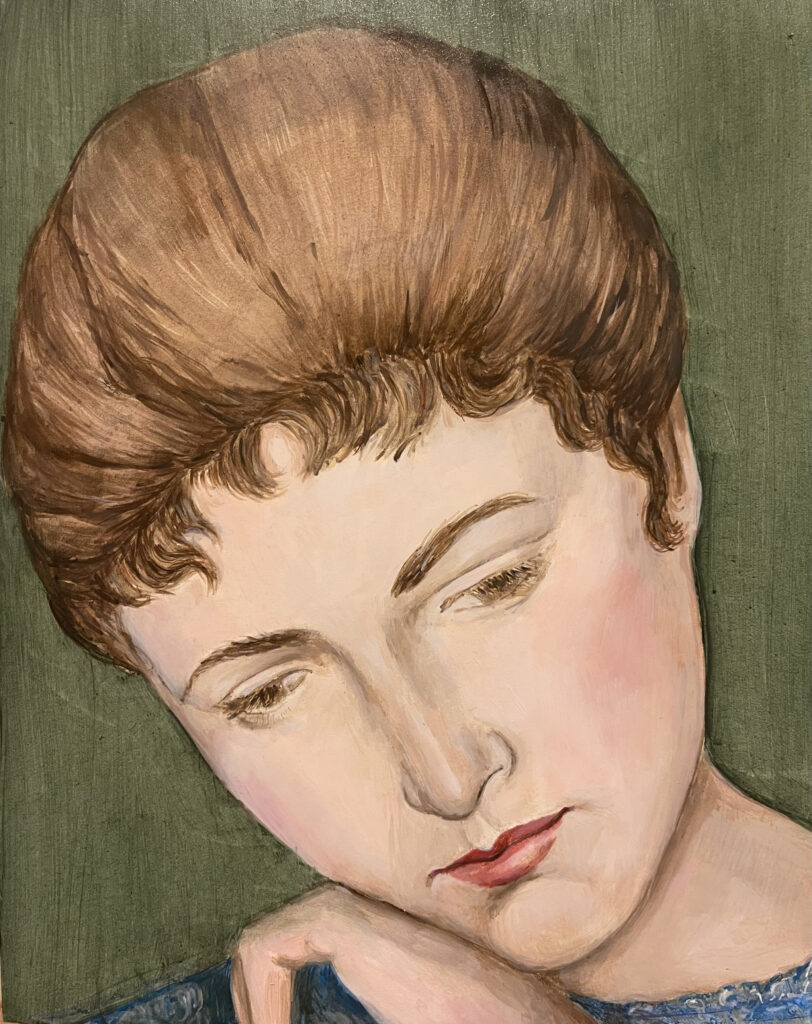

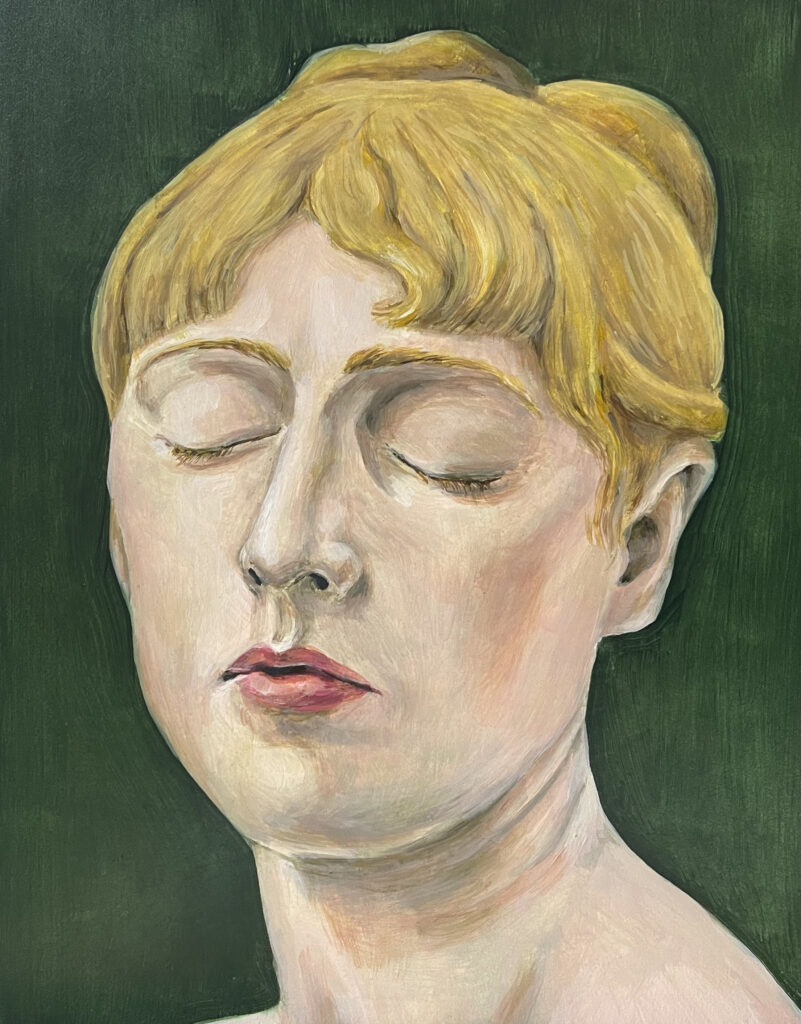

Turning the table on traditional narratives, Fortnum has decidedly presented these women as artists, not muses. Rather than simply painting their portraits, she has focused on portraying their sculptures, pulling their creations into her frame.

Camille Claudel, ‘Young Woman with Closed Eyes’, c. 1885

At the same time, she has celebrated these women artists’ own female muses. For instance, she has depicted Camille Claudel’s terracotta sculpture, Young Woman with Closed Eyes’ (c. 1885), as an oil portrait – see above. Another example is her representation of Sarah Bernhardt’s marble sculpture of fellow artist, Louise Abbéma (1878) which is held in the Musée d’Orsay, Paris – see below.

Through her series, Fortnum focuses on the female gaze. There is real humanity and almost a worshipful attitude expressed in these women artists’ sculptures of other women, often a friend, peer or fellow artist. Rather than objectifying their female muses, there is instead an emphasis on their ambiguous expression and complexities of identity, an understanding between model and maker. As the artist has explained:

‘I’m working from women’s depictions of women with their eyes downcast or closed or looking away. I enjoy the ambiguity implicit in both the signalling of empowered absorption or self-containment alongside a reading of social conformity and female modesty’.

Fortnum aptly describes her practice as ‘exhuming’ these artists’ works, much of which now only exists in photographic documents, ruminating on legacy and what it was like to be female artist at that time. There’s a haunting quality to these images, which act as commemorative obituaries of female sculptors and their work, much of which has been lost.

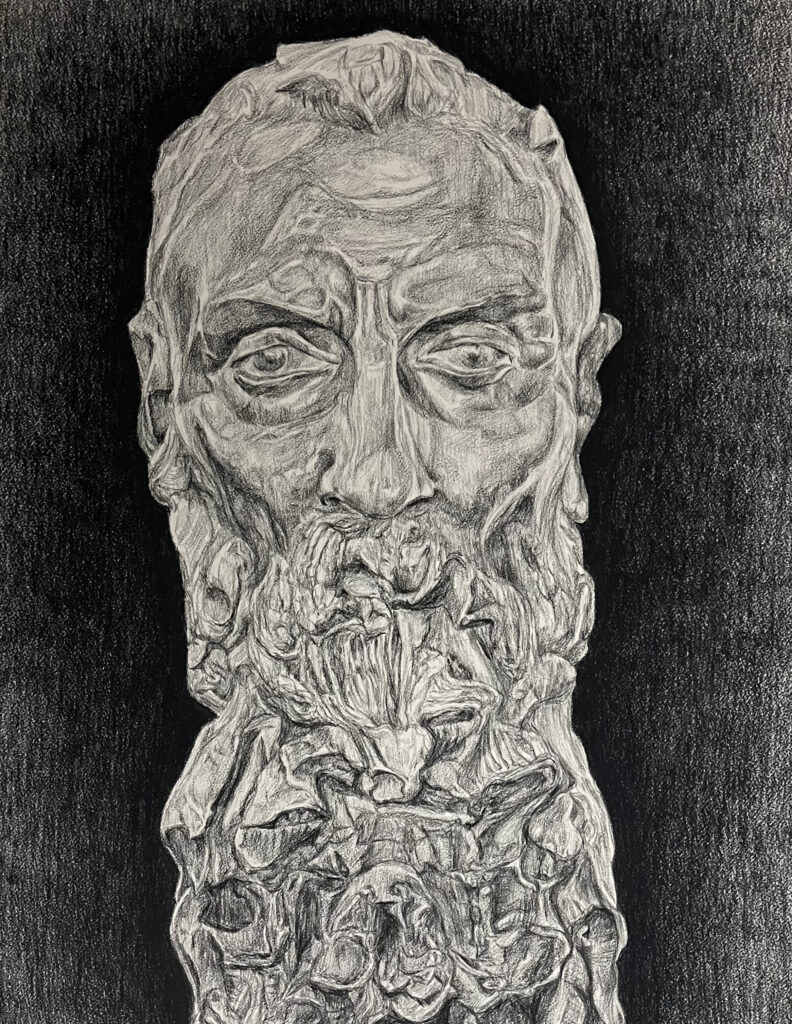

Further subverting art history, with its emphasis on the female models of male artists, Fortnum also includes these female artists’ male muses. Accompanying drawings, made with dense carbon pencil, are based on sculptural portraits of men produced by these women and the images are often of figures close to the artists – partners, teachers, fathers. Among them is a portrait of Rodin, based on the bronze ‘Bust of Rodin’, 1892, by Claudel which belongs to the Musée Rodin in Paris.

However, drawn in tones of grey, the spotlight shines brightest on the great women sculptors of this show. Fortnum’s emphasis is on their female gaze and subject matter, so often other women artists, who continue to inspire her practice today.