There’s a storm in a teacup, at Midlands Arts Centre, as part of the group exhibition ‘Worlds Away: Art, Nature and Wellbeing’. Birmingham-based artist Paul Newman explains that his intriguing and “autobiographical” painted object is about the “struggle to alleviate anxiety from the pressures of life”. Art, for Newman, is a therapeutic activity and he is far from alone in using it to benefit his mental health. But, to what extent can art really help both maker and viewer?

Mental health in the UK is getting worse, according to a report published this September by the Centre for Mental Health. 8.2 million people live with at least one condition such as anxiety or depression, and approximately 1 in 4 of us will experience a mental health problem each year, with record waiting times for support from NHS services.

As well as offering medication or therapy to patients, the NHS has embraced ‘social prescribing’, based on research proving that mental health can be improved by spending time in art, nature, exercise, music and social activities. At least 900,000 people will be referred to social prescribing by the end of 2024, or at least that’s the aim.

But some people have always used art as form of therapy – they are called artists, as MAC’s sumptuous new show proves. “Art”, Grace A Williams, explains, “is a form of non-verbal expression, as such it opens lines of communication for those struggling to articulate feelings and experiences into language.”

Across the back wall stretches her digital, floral wallpaper, ‘Horai’. More than just a pretty picture, it addresses climate anxiety, which is a major theme of the exhibition. As Williams explains, “Art cannot and will not solve the complexities of climate anxiety but individuals can externalise concerns and fears through it.” Growing from her wallpaper are indigenous plant species that sadly won’t survive a warmer climate.

Similarly, artist and researcher Frederick Hubble creates art that allows him, as well as viewers, to confront climate anxiety. In ‘Storm Archive’ he has lined shelves with glass jars, labelled with the names of storms which have swept across the UK. He says:

“I think putting storms in jars for me was a way of making sense of the scale and the frequency of our changing weather patterns. They are a record both on a personal and global scale, they tell the story of my food cupboard (I often use condiment jars that are nearly empty) and the story of the storms that hit this island.”

Beyond tackling climate anxiety, art has hugely benefited Hubble’s health by “supporting him when he has felt isolated, giving him focus, driving him to continue through periods of mental illness”, and helping him to find his “own identity.”

Paul Newman, too, recognises the therapeutic power of art, “I always feel on uncertain ground and the landscapes I paint, often with a weary traveller, are unstable in grounding and destination. The painting process is one form of coping with these feelings.”

He reflects on the transformational impact of art on viewers, as well, by referencing paintings which have “stayed with” him after a museum trip. In ‘The Visitation’ he pays homage to one such work – John Constable’s ‘Hadleigh Castle’, 1829, in which clouds swirl around crumbling ruins. “Always drawn to the melancholic Romantism of a certain type of stormy landscape painting”, Newman recognises that “recent awareness of climate change is something that has filtered into the narrative” of his paintings, while worsening feelings of “instability” in the world.

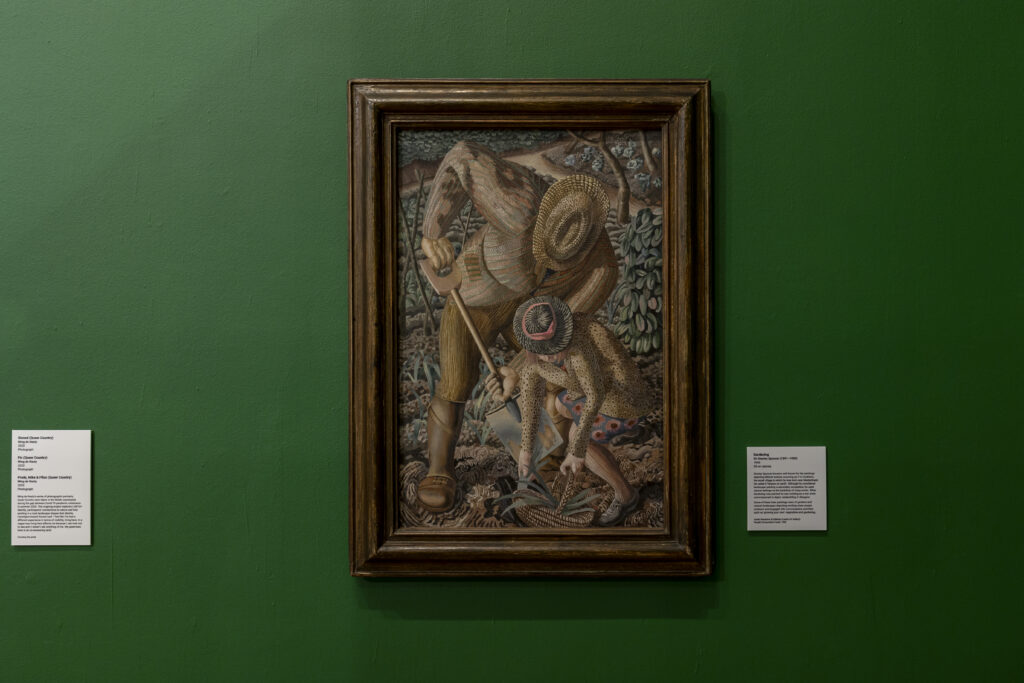

Such conversations are not new, as demonstrated by several modern master paintings in the exhibition. While Britain was at war, Stanley Spencer took solace in his garden, picturing the landscape as something fragile to be nurtured and protected, as framed in ‘Gardening’, 1945.

Likewise, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye’s painting, curiously titled ‘Condor And The Mole’, 2011, portrays two girls taking pleasure in nature: unposed, they dig their feet into the sand, inviting viewers to share in their wondrous exploration of the world.

Also on display is an enormous, patterned textile, filled with faces, by self-taught artist Madge Gill, who has a retrospective in the downstairs gallery. During her 30s, Gill turned to art as a form of therapy to overcome tragedy and ill-health. Painting, drawing, doodling and sewing, she transformed trauma into joyful artworks which read as an outpouring of emotion.

A transformative exhibition, ‘Worlds Away’ invites viewers to find solace in imagery of the natural world. Art is not a simple fix for mental health problems and galleries should not be burdened with that responsibility. But, for some, making or looking at art can alleviate anxiety and depression. Much like Hubble’s work, art is a jar of hope, bottled and sitting on a shelf, waiting to be released.

This text was originally published in the Birmingham Post.