‘Good artists copy, great artists steal’ – Pablo Picasso

Cultural appropriation, once discussed in debates amongst academics, has moved into the mainstream media. Teen Vogue recently published an article on ‘How to Avoid Cultural Appropriation at Coachella’. Australian model Shanina Shaik had obviously not read the piece, and shared a photo of her braided hairstyle on social media, which quickly came under fire, as followers accused her of ‘appropriating black culture’. This crusade against cultural appropriation can also be found in the art world. Last year an exhibition in Canada was cancelled because of the artist’s ‘cultural genocide’ of tribal art. So, let’s take a look at cultural appropriation and art.

Cultural appropriation & aesthetics from antiquity onwards

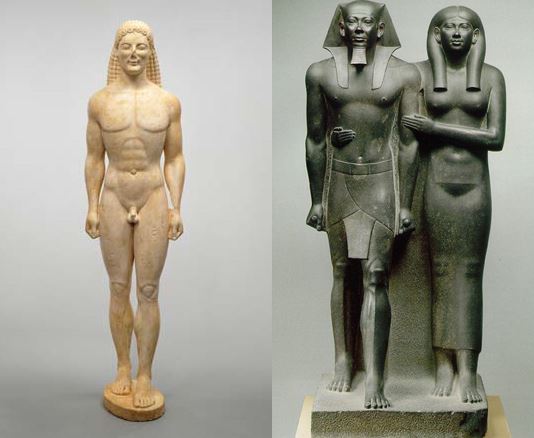

Cultural appropriation is inextricably tied up with aesthetics and it is not a new phenomenon. If we take a look at art history, cultural appropriation has been going on for centuries, and many of the world’s most celebrated art movements and objects are the result of it. Greek sculptures, and particularly their freestanding, life-size nudes, called ‘kouros’, clearly show the influence of Egyptian art. The Romans appropriated large amounts of Greek culture, and so on.

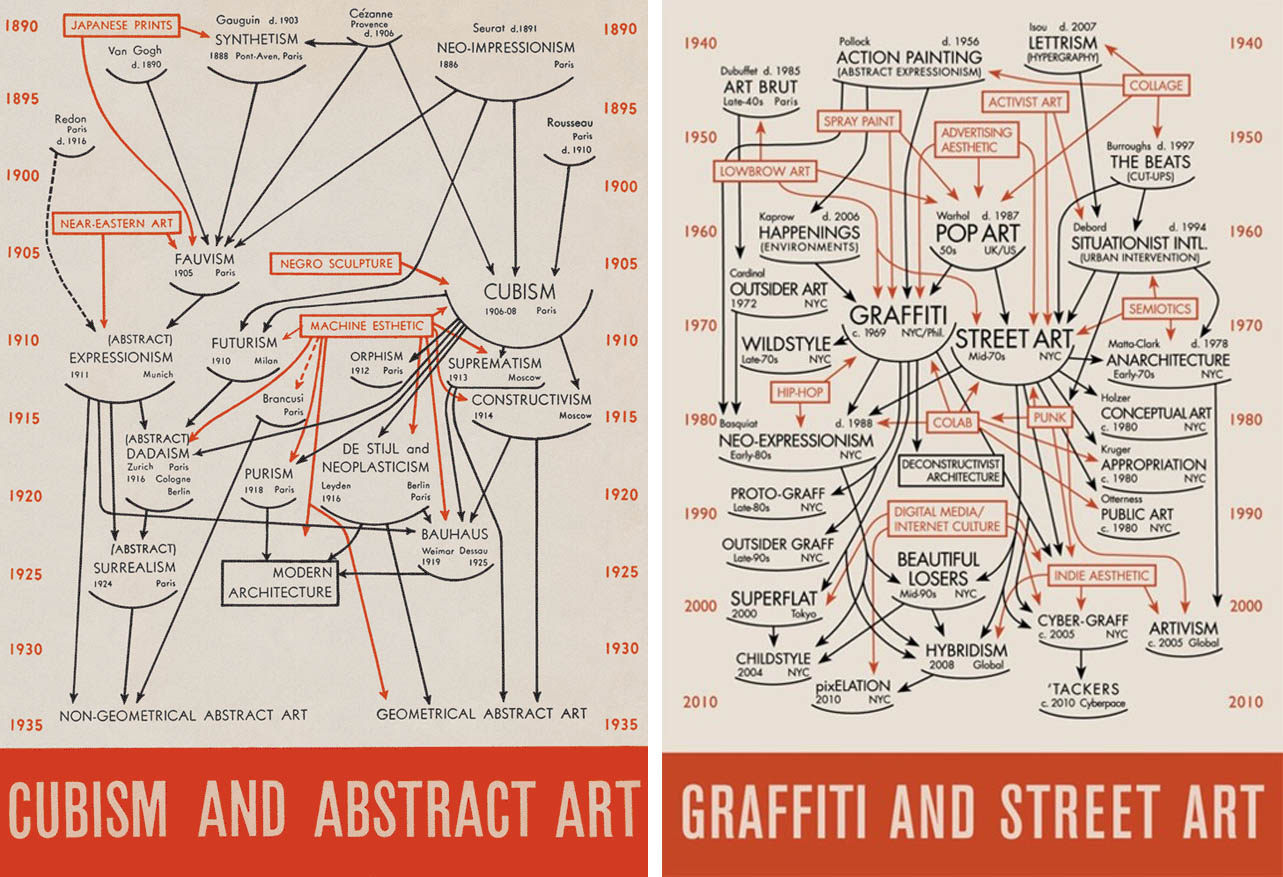

Fast-forward to the 20th century and ‘great’ artists, including Picasso, Gauguin and Matisse, formed modernism out of appropriating other cultures’ art, crafts and artefacts into their revolutionary practice. If you haven’t seen Alfred Barr’s famous flow-chart for modern art, it shows the notion of borrowing art forms from other artists and cultures played a defining role in creating modernism.

If cultural appropriation went some way to forming modernism in the arts, is it always a bad thing? I suggest we start by asking: what is cultural appropriation?

‘This term is used to describe the taking over of creative or artistic forms, themes, or practices by one cultural group from another. It is in general used to describe Western appropriations of non‐Western or non‐white forms, and carries connotations of exploitation and dominance. The concept has come into literary and visual art criticism by analogy with the acquisition of artefacts (the Elgin marbles, Benin bronzes, Lakota war shirts, etc.) by Western museums’ – The Concise Oxford Companion to English Literature.

From this definition, it is clear that it is the connotations of power over minority cultures, which make it such a negative label, and not one to be taken lightly. What it infers is exploitation and racism.

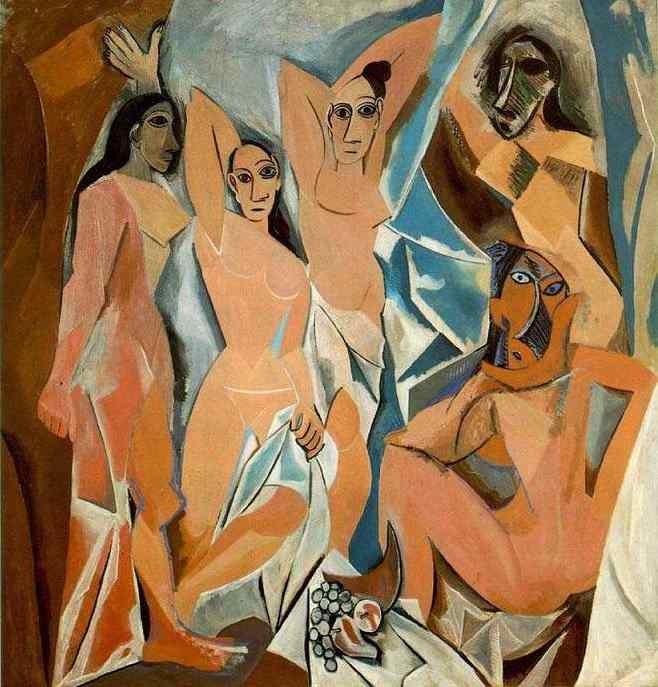

Picasso, African art and appropriation

Let’s return to Picasso and consider his masterpiece ‘Les Demoiselles D’Avignon’, which is famed for its incorporation of African masks. Picasso had seen African masks in several museums in Paris, and was intrigued by their formal and spiritual qualities. What complicates this matter is that it was the context of colonial exploitation that brought African art into the domain of French culture, and made Picasso’s interaction with these masks possible. This fact raises the question: should we discuss this painting within the framework of cultural appropriation?

This painting is housed in New York’s MOMA, and describing the work on their website the museum writes that Picasso was “inspired by Iberian sculpture and African masks”. The Metropolitan Museum in New York, in their discussion of the picture, talk about how Picasso ‘blended’ African art into the image, and “recognised the spiritual aspect of the composition”. There is no mention of the negative term ‘cultural appropriation’ here.

The language of appropriation

It is not just history but language which plays a crucial role in this debate. Where are the boundaries between appropriation and the more positive, and closely associated, labels assimilation and appreciation? And who decides upon this classification? That lies in the eye of the beholder: what for one person is assimilation, for another is appropriation. Art history, and museums, can frame a work within a particular way, and distinctions are demarcated in the language art historians choose.

Art historians, such as Edward W. Said, have strongly criticised cultural appropriation. Said’s seminal book entitled ‘Orientalism’ has become one of the founding principles of post-colonial and critical race theory, defining Orientalism as ‘the way that the West perceives of — and thereby defines — the East’. At the heart of his discussion is the link between cultural appropriation, exploitation and racism, and this is the implication whenever someone uses the increasingly popular label.

The growing conversation about cultural appropriation – now out in the open – is definitely a good thing. What we must not forget is that cultural appropriation has been going on since the dawn of (art) history. Moreover, cultural crossover and conversations have resulted in progress, in the arts and beyond. If we continue in this crusade against so termed cultural appropriation, the risk is that we segregate, censor and police the arts, which cannot be a good thing. This heavily loaded term should certainly be used with care.

Further reading

Want to read more on this controversial topic? I recommend the following books:

James Young, ‘Cultural Appropriation and the Arts’.

This book sets out the positives and negatives of cultural appropriation in list form. Although it’s a text book, it’s not overly academic and a great starting point on the topic.

Edward Said, ‘Orientalism’.

How do cultural appropriation and art history intersect? In this post-colonial classic, Edward Said discusses Orientalism, defined as the West’s patronizing representations of and attitudes towards “The East” (Asia, North Africa, and the Middle East) through specific artworks, literature and history. It’s beautifully argued, persuasive and conclusive.

James Clifford, ‘The Predicament of Culture’.

In The Predicament of Culture, James Clifford looks at the West in its changing relations with other societies. He explores cultural practices such as anthropology, travel writing, collecting, and museum displays of tribal art. He shows how apparent authoritative accounts of other ways of life are often fictions, now actively contested in post-colonial contexts.

Ruth x