American painter Danielle Orchard riffs on art history’s masters to offer an updated, feminist view of the muse. It was an honour to write the following essay for her major solo exhibition, Is It Light Where You Are? to take place at Perrotin Shanghai from March 15 — May 25, 2024.

From her Massachussetts studio, Danielle Orchard paints quietly charged, domestic scenes of solitude. If there’s an immediate sense of familiarity to her paintings, it’s because she riffs on the great modern masters: Matisse, Picasso, Hopper. But, with a disruptive brush, she assimilates their symbolism only to reclaim reality through her own contemporary lens.

Central to Orchard’s practice are notions of the muse, represented as a reclining female nude throughout centuries of art history. Having previously life modelled herself, Orchard complicates traditional ideas of women as passive objects of desire. Instead, her sculpturally-formed figures – pictured from surprising viewpoints and often from above – are unposed, and unguarded.

However, in this new series, women are curiously, and strikingly, absent. It’s as if the missing subject has just walked away from her dressing table, departed the kitchen table, or left her unmade bed, as is the case in Is it Light Where You Are? (2024), from which the exhibition takes its title.

Illuminating the space is a glowing oil lamp, which has been lifted from a Balthus painting. Frequently taking such art historical references as her starting point, Orchard asks, ‘what could I add to this?’. On this occasion, the flame has attracted a fragile, white moth, bringing quiet tension to the empty bed scene in which there is no dreaming muse to be found within the sheets.

On the surface, Orchard’s sitter has evaded all depiction. Yet, as the artist points out, “The female protagonist is still present” throughout the series. She appears in a framed photograph, a lipstick-stained wine glass, a red jacket. With such signs of life, it’s as if she has just stepped outside of the frame, adding mystery to the tableaux she’s left for the viewer to interpret.

Removing bodies has also given Orchard the freedom to emphasise other psychological elements in these compositions, in which she has brought previously background items to the fore. Still life has always been important to the artist, who imbues common objects with drama and meaning, allowing them to convey emotion, as they do more than ever in this series of moments between events.

The table set theatrically for two in Morning Daggers (2024) creates an eerie atmosphere. Placed on a crisp plain tablecloth are no forks, only knives, their sharp ends painted red. Is this jam or something more sinister? The viewer is left to wonder. A single, staining drop suggests there is more to this breakfast than first meets the eye.

Served up on small plates, eggs hold yet more powerful symbolism, continuing an earlier theme from Orchard’s figurative works in which she used such iconography to address fertility. Yet, there is a timeless quality to her paintings, indicating that it is women’s experiences, more broadly, that she is interested in portraying.

In other images, still life objects stand in more directly for the female form. The human-sized tulips in The Flood (2024) have sprung to anthropomorphic life, blooming huge and heavy heads, which wilt as it rains outside. Meanwhile false eyelashes discarded in a small dish in Snow Drops (2024) act as a metonymic portrait, holding noirish potential.

Light, too, assumes a metaphorical role inside Orchard’s rooms, playing on walls like thoughts inside the mind. Slicing through each of the lusciously painted scenes are geometric shadows and angular light patterns, their dividing lines seeming to represent half-remembered, half-told memories or dreams.

Having developed a more metaphysical and abstracted approach for this body of work, the artist has consciously sought to invoke “sensations of the dream” by making unusual colour choices, disorienting her viewers. The loud yellow walls of a bathroom, in which the taps have been left running, contrast with a bedroom painted hot pink. At times, she has added to ambiguity sources of artificial light, inviting questions about the time of day or night: is someone up early or late?

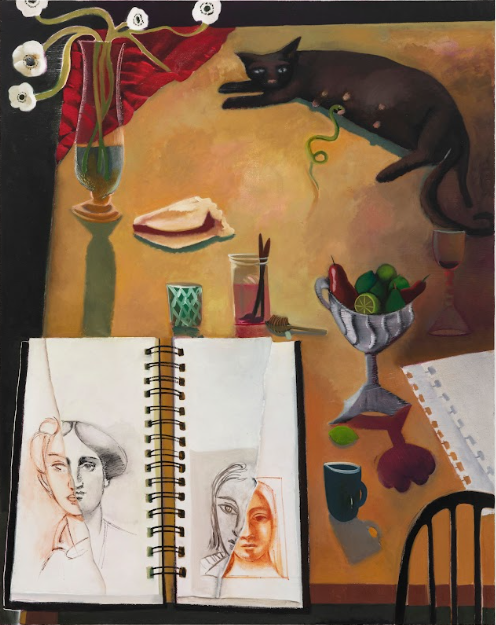

Orchard has also conjured notions of the uncanny and unease by casting symbolic creatures as sidekicks to the furtive heroines within her enigmatic interiors: a black cat stalks between several scenes, while a lifeless bird appears to have drowned in its own water bath in Sight Rhyme II (2024), carrying the feel of a dark fairy tale.

Snow Drops, 2024, Oil on canvas

In Evening Chimera (2024), torn and overlapping drawings reveal chimeric faces in an open sketchbook. Formed by chance, these composite creatures invoke the surrealist artists who allowed images to emerge from automatic drawings or rubbings. Representative of the potential of the unbridled imagination, they also point to Orchard herself, a painter who stays up late to work.

Like her subjects, Orchard is not represented directly in the frame. Freeing women from all possibilities of a voyeuristic gaze, the artist reveals more about their interior lives. Painting psychological portraits –defined by an interplay of dark and light, the real and imagined, visible and hidden – she unsettles viewers’ expectations through disquieting narratives from, and about, the female perspective.