Art history has been built upon mythical images of the individual male genius. Working alone in his studio, he is driven by his unstoppable imagination. But behind every great man, so they say, there’s a woman, and art’s masters wouldn’t have got anywhere without their female muses, models, wives and fellow artists, whose contributions have largely been overlooked.

Changing these traditional narratives is an enchanting exhibition at Birmingham’s Winterbourne House and Garden, ‘Totally Curious, Ever Inventive: Berthold Wolpe and Margaret Wolpe’. In their first joint show, this great artist couple of the 20th century are being celebrated on equal terms, with the important message: creativity flourishes through collaboration.

It starts on the staircase leading up to the second floor, where high walls have been decorated in rows of colourful book covers. ‘King Arthur’, ‘The Bell Jar’ and ‘The Fine Art of Mixing Drinks’ and are among the eclectic titles on display, advertised through lively fonts.

They are among over 1,500 Faber & Faber front book covers created by typography and graphics legend, Berthold Wolpe. “All his covers show great strength and energy. And the fun and power of the human hand so much lost in the sterile output of modern computer-generated covers”, says the show’s curator, Phil Cleaver.

The same energy continues in a room filled with his hand-drawn fonts, calligraphy and teaching alphabets. ‘The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog’ reads one sentence, often used by designers as it includes every letter in the alphabet, which Berthold has imagined in inky, characterful letters.

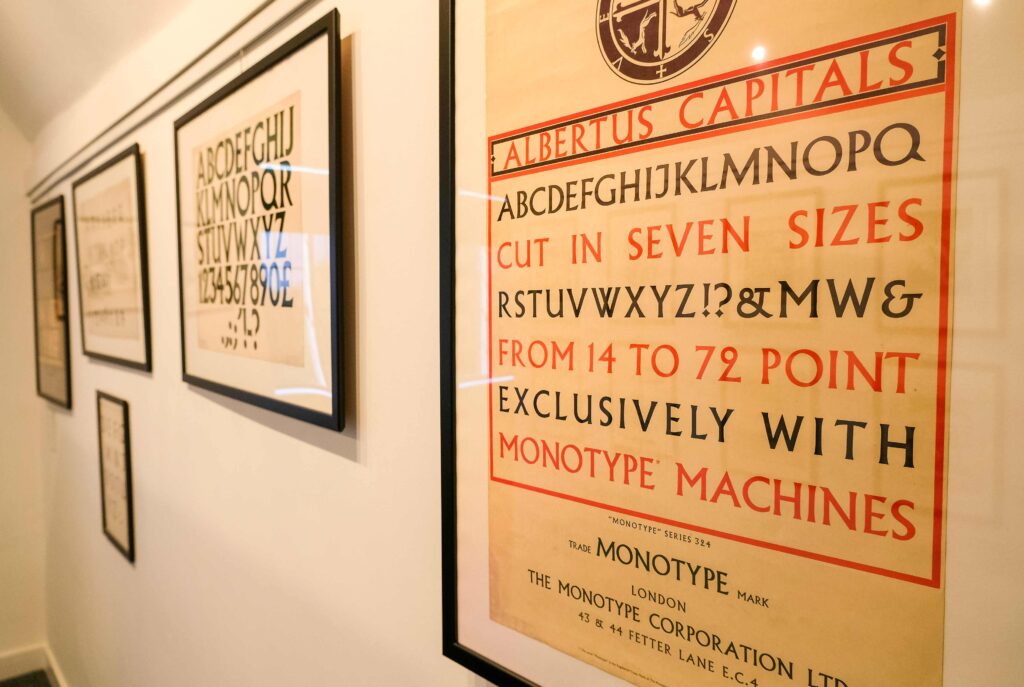

Also on display, in bold black and red capitals, is the Albertus font, which he invented in 1932. This has been used on City of London street signs, printed in The Times newspaper, and is still in regular use across various media.

We don’t always know the names of font designers, although Berthold has been recognised in exhibitions previously, and widely credited for leaving “a pervasive and permanent mark on graphic design”, as Cleaver writes in an accompanying book.

However, the unacclaimed partner in this marriage of artists is Margaret Wolpe, whose work is displayed side-by-side with her husband’s for the first time. Not only was she a prolific illustrator and painter, but she also turned her talented hands to sculpture, wood carving, and jewellery making. “You name it, she did it, and she did it well”, says Winterbourne’s Collections Officer, Henrietta Lockhart.

A highlight is a case of her jewellery made from the most unexpected and found materials, including electronic components. Taught at one stage by Henry Moore, she created figurative and abstract sculptures, including a mesmerising wooden mermaid on display. A handmade quality defines both artists’ work, and they travelled far and wide, always searching, in an era of mass production, for quirky originals.

In another room are a series of Margaret’s sensitively painted portraits of friends and family members. She attended life drawing classes well into her 80s, while also using her children as models. Included in the show is a thoughtful depiction of her eldest daughter Sarah, reading. A fitting inclusion, it captures a young woman just about to start her studies at the University of Birmingham.

In another oil painting, she has framed her husband sitting on the beach at Bishopstone, East Sussex. While Berthold is immersed in his book, Margaret is busy painting, and three of the children are messing about in the sea in the distance, unsupervised, while the fourth has disappeared from view. The joyful image captures the couple’s parenting style in the 1950s, which enabled Margaret to be both a mother and artist.

Objects of their creative partnership are also included in a display case of pens, watercolours and gloves. The couple had married in 1941, following similar training in traditional craftsmanship, and developed together as artists. “Two talented artists living and working together will only not influence each other, but will also make both their art grow, and improve”, says Cleaver.

They did collaborate more directly at times, both formally and informally. “I heard Berthold often ask Margaret something like, ‘how do the back legs on a lion go?’, and Margaret would draw it for him in the back of an envelope,” explains their daughter Deborah Hopson-Wolpe, who is also an artist. The displayed book ‘Traditional Recipes of the British Isles’, has both of their names credited on the cover, as they worked jointly on its illustrations, sometimes even contributing to the same image.

The whole exhibition has, in fact, been a family act; while their son Paul has been responsible for hanging the pictures, Deborah has curated the display cases at Winterbourne, which is the ideal domestic space for this show, given that it was once home to John and Margaret Nettlefold who lovingly created the garden together.

Rebalancing views of the couple, this delightful show of creativity brings Margaret out of Berthold’s shadow and presents her as his artistic equal, who worked alongside and in creative dialogue with him. Emphasising the handmade, this exhibition proves that many hands make great and imaginative work.