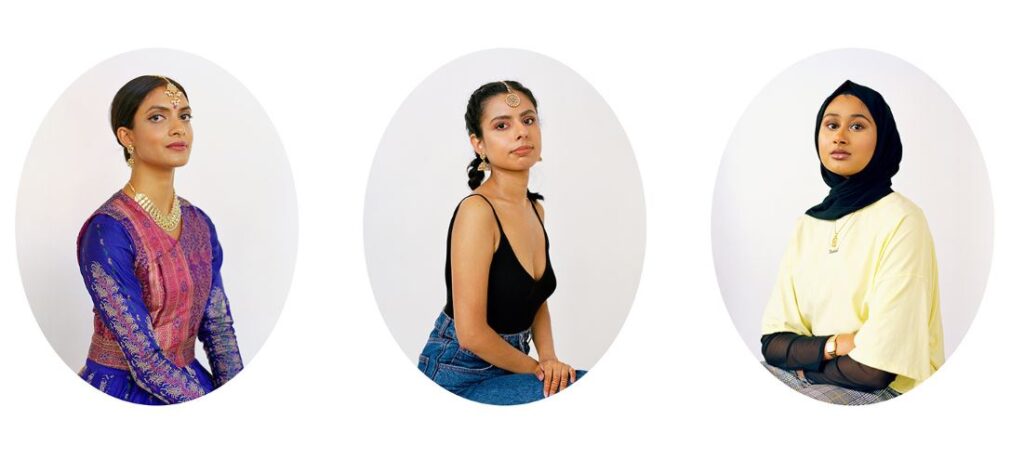

Photographic artist Arpita Shah is replacing male Mughal emperors with modern female sitters in her empowering new series, Modern Muse, which has recently been acquired by Birmingham Museums Trust for Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery.

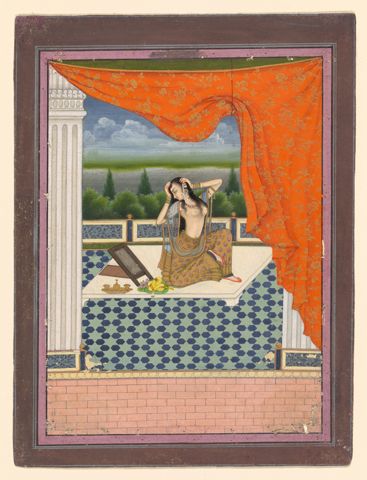

Shah recognised that South Asian women, in traditional imagery from colonial times, are typically framed as passive characters in paintings, reduced to the role of consort or lovers, and depicted in sensual and subservient terms, never looking directly at the painter. Frequently framed by a window, they are found holding the suggestive narcissus flower, looking at themselves in a mirror with desire in their eyes, reading a book of poetry or holding a cup of wine.

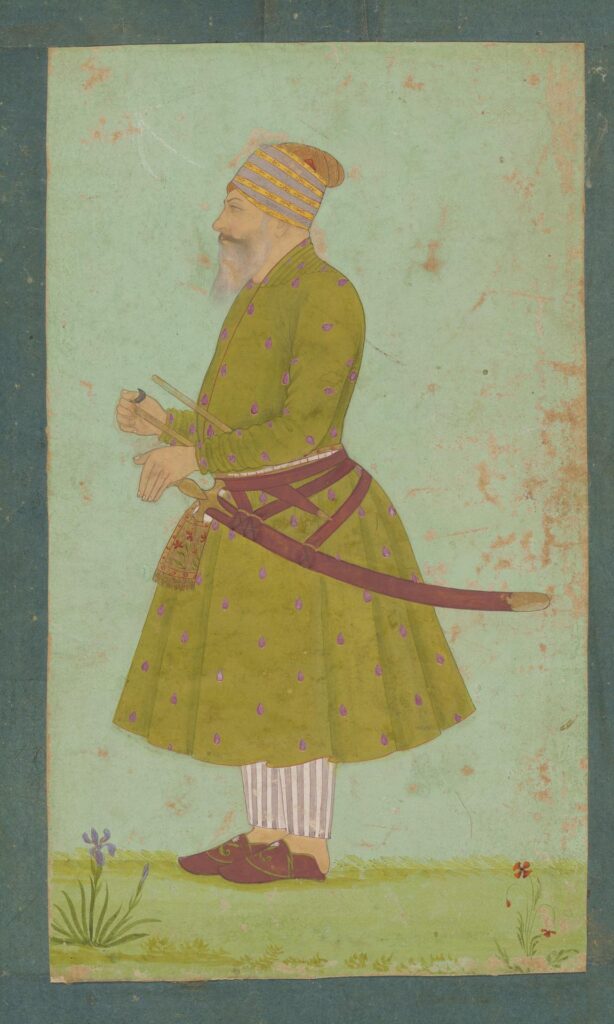

In ‘Modern Muse’, a series commissioned by GRAIN and supported by Arts Council England, she challenges that narrative; her sitters express their confidence through a more direct gaze and pose. In this manner, they are more akin to male emperors and rulers, positioned alone, against a colourful background.

Her series, in which many of the women wear a headscarf, also challenges dominant, reductive narratives, both historical and contemporary, in which veiled women are deemed oppressed subjects. Fabric is an important part and signifier of each of her modern muse’s complex identity, much like the hunting coats, jewellery and swords which mark an emperor or sultan’s status in miniature painting.

Shah has interviewed each South Asian woman in the series, including their words alongside their image, as a means of giving them “more agency”. Her muses include an artist, academic, activist, dancer and educator, among others, who all live and work in Birmingham and the West Midlands.

Inspired by, while subverting, Mughal portraits, Shah elevates the status of her female sitters, in order to give them visibility, allow them to be seen on their own empowered terms, while diversifying the very notion of who and what a muse is, on a museum’s walls.

Let’s meet some of her muses…

Nilupa, Artist & Educator

I was born here, and my family come from Bangladesh. Growing up in Birmingham I’ve always been surrounded by a very diverse and multi-cultural environment. I didn’t feel like a minority, I would see a lot of people who look like me and share the same experiences as me.

I found that through my arts practice if you can’t fit into any of the spaces you inhabit make your own space and live in that. I’m British, I’m Bangladeshi. I’m both. If you’re not okay with that, then that’s your problem, not mine. Trying to narrow myself into one, feels somewhat disrespectful to all the subcultures I am fortunate to be part of.

There’s representation now of Muslim women owning their spaces and it matters. If you can see yourself represented in different ways, be it through career choices or style of clothing, this can create a positive impact. It’s wholesome to be able to see this around us and that there is no one right way to exist.

Vidya, Kathak Dancer

I am a first generation British Asian and I have been training predominantly in Kathak, which is a North Indian classical dance. Both India and Uganda have played a large part in my upbringing because that shaped my parent’s thoughts and values.

Both my parents have gone through a lot in their lives, they have both been very liberal in bringing me and my siblings up in this country, making sure we are connected to our Indian culture but also understanding that the culture in Britain has a lot to offer Every generation is like an evolution and it’s interesting to see how thoughts, traditions and cultures have been passed on, but also being changed constantly and questioned.

Being British for me has got to a place where it’s allowing a lot of cultural exchange, which is a benefit for us and our generation now. Being British is about questioning and finding out, a deep place of exploration. What it means to be British is an exchange and being aware of the British past.

Jaskirat Kaur, Artist

I was born in the UK, my family are from Panjab, Northern India and we are all Sikhs. I like it when people ask and are curious about my Dastar (turban), rather than keeping that curiosity within and not exploring it. I enjoy talking about my identity, so am open to people asking me about it.

Personally, the Sikh Dastar shows that you’re loyal to Guru Nanak Dev Ji. I am covering my Kes (hair) because it is one of the five gifts in Sikhi. Covering, growing and never cutting your hair ensures you retain the flow of energy in your body. It is really important when you meditate to keep it intact and coiled on the top of your head. Covering your kes is also respectful, hygienic and practical for meditation and focus.

I am proud to be Panjabi and from the land of the Gurus that laid the foundation of Sikhi. I identify as being from the UK but my home is also Panjab.

Rupinder, Writer

I was born in Handsworth and I’ve always been into South Asian poetry and history. I started writing around the age of 19. It was my Nana Ji who first came to England from Delhi. Growing up in the Midlands as South Asian, specifically- Punjabi, meant you knew you all about Bhangra and all the best places to get chaat. My love for music is what drew me towards Punjabi literature and started my artistic journey as a poet leading onto various creative outlets with writing and performing.

Through my own research of wanting to know more about South Asian Arts I realised how many amazing women there are in the art world. I see myself as a free spirit that chooses what I wish to make of my identity. I’m very Punjabi, very South Asian, I identify with the pre-partition Punjab and the whole of South Asia. But I also critique, and question out-dated customs that should no longer be part of our cultures and identities.

Harr-Joht, Research Manager

I’m third generation Punjabi Sikh and I studied Art History in London before working in cultural programming and arts administration.

I have a personal interest in how faith, devotion and spirituality manifests in contemporary arts and culture. People are weary about the language of religion, yet our faith literacy has lots of room for growth. It is so important that we accept our limitations and remain open to different ways of being, knowing and seeing the world.

The language barrier, compounded by my lack of attention and interest at Punjabi school as a kid, has been difficult for me and has limited my capacity for intergenerational connection, particularly with my grandmother. Though we have a loving relationship and our non-verbal communication keeps us going, my lack of Punjabi conversational skills is ultimately so restrictive and frustrating. The reality is that the language will erode if it is unspoken. Seeing more young Punjabis online owning the language and feeling proud of this is empowering and important.

You can meet, and read more about, Arpita Shah’s inspiring modern muses here